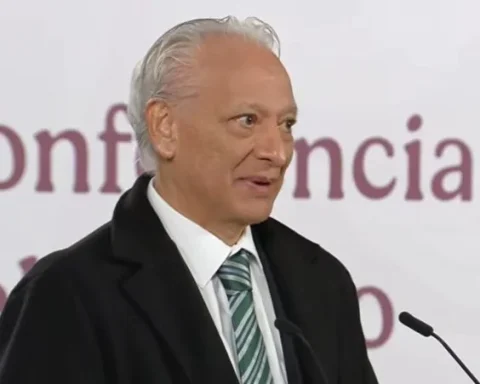

MADRID, Spain.- Former Minister of Justice Óscar Manuel Silvera Martínez assumed the presidency of the Supreme People’s Court (TSP) of Cuba this week, replacing Rubén Remigio Ferro, who headed the country’s highest judicial body for almost three decades. The appointment, approved by the National Assembly in December and formalized during the opening of the judicial year, confirms the political and institutional continuity of the Cuban judicial system.

Silvera Martínez is not a figure alien to the courts or state power. Graduated in Law, he began his career in the judiciary in municipal and provincial courts of Granma, until he rose to positions of greater responsibility within the judicial apparatus. Before joining the Council of Ministers, he was vice president of the Supreme People’s Court itself, a key position within the country’s judicial structure.

In July 2018, with the arrival of Miguel Díaz-Canel to power, Silvera was appointed Minister of Justice, a position he held for more than seven years. From that position, he was linked to the application and supervision of the legal framework that has accompanied the tightening of repression in recent years, including regulatory reforms and the operation of a judicial system accused of lacking independence from political power.

One of the most controversial episodes of Óscar Manuel Silvera Martínez’s management as Minister of Justice was his role in the State’s intervention in Cuban Freemasonry, a conflict that showed the extent of government control over civil associations. From the Ministry of Justice, Silvera defended the so-called “guiding role” of the organization over associations, relying on Law 54 of 1985, and publicly denied any state interference. However, during his mandate, the MINJUS endorsed the imposition of Mayker Filema Duarte as a Masonic authority, a figure rejected by large sectors of the Grand Lodge of Cuba, who described him as a usurper.

This action was interpreted by freemasons and independent jurists as a direct political intervention in the internal affairs of a historically autonomous organization, by ignoring its own electoral processes and deepening the internal crisis of Freemasonry. Under Silvera’s direction, the Ministry used legal and administrative mechanisms to subordinate Freemasonry to State control, setting a worrying precedent for the rest of the civil associations on the island.

During his time at the head of MINJUS, especially in 2021 and 2022, Silvera was one of the main defenders of the Family Code, submitted to a popular referendum in September 2022. The then minister presented the norm as a legal advance, while independent sectors questioned that the legislative process was developed in a context without guarantees of political pluralism or civic freedoms, and warned that the new legal framework did not offer effective protection to those who dissent from the system.

His return to the Supreme Court does not represent a break, but rather a return to the judicial leadership from a position reinforced by his time in the Executive. Silvera has historically been considered an official loyal to the power apparatus, with close ties to political control and state security structures.

During his inauguration speech, Silvera made this alignment clear by stating that the judges will defend the Revolution and the current political system, a message that once again calls into question the principle of separation of powers in Cuba. Far from alluding to guarantees of judicial independence or profound structural reforms, his intervention was marked by ideological references and by the reaffirmation of the role of the courts in supporting the political project of the regime.

The replacement of Rubén Remigio Ferro—responsible for emblematic sentences in high-profile political processes—by Silvera Martínez has not been interpreted as a sign of change, but rather as generational continuity within the same control model.

With this appointment, the Cuban regime closes the circle between Government and justice, placing at the head of the highest judicial body a leader trained, promoted and tested within the State’s own political apparatus.