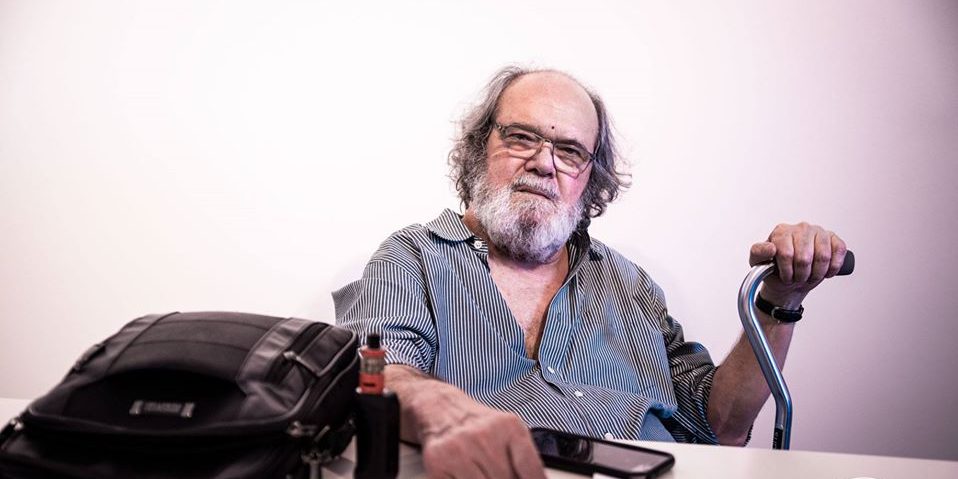

With extensive award-winning work in Cuba and other countries, Félix Luis Viera is one of the most prominent Cuban authors of the last 50 years.

HAVANA, Cuba – With a solid narrative and poetic work – six collections of poems, three books of short stories and eight novels – that has been awarded in Cuba and other countries, Félix Luis Viera (Santa Clara, 1945) is one of the most prominent Cuban authors of the last 50 years. Resident in Miami since 2015, he kindly agreed to answer this questionnaire to CubaNet.

How did you get started in literature?

I always had that obsession, but I couldn’t get into it when I was a teenager. I am an only child, at the age of 16 I lost my father, my mother and I were left alone, and to survive, I had to urgently continue a mid-level career—which I had previously begun, hesitantly—very distant from the Humanities: accounting and economic control. Thus, I was far from an environment conducive to the stimulation of literary creation, and at the same time I had to work day after day—sometimes night after night—and sometimes Saturdays and Sundays on something I hated, plus assist when required to do what they called “productive work,” in the field or in a factory. However, he was writing little things that he saved for someday – most of them did not pass the test of time – while he waited for a more favorable environment. It was hard, very hard, to resist without giving up. Until, in 1979, with the help of some friends, I was able to move to the Directorate of Culture and then life became less arid for me. Already in 1976 I had received the David Prize for Poetry and that helped me with the transfer. Everything was made more difficult because I lived in a provincial city.

In which field do you feel more comfortable, in poetry or narrative?

I couldn’t tell you, in both I feel, as I usually say, in a wake and a festival. Literary creation (I don’t know if it will be the same for other authors) sometimes turns out to be an intimate celebration and other times an intimate regret. It is an essential curse.

Never as in “The Heart of a King” was the atmosphere of the 1960s in a city in the interior of Cuba so well described in a novel, in this case, Santa Clara. How much is autobiographical in it?

A lot. The characters are taken from real life, or at least, the fundamentals of them and their environment, men and women who existed and still seem to me to exist. That novel has received a lot of attention from critics. Some of the people who have written about it affirm that, although Santa Clara is the direct reference, it is a story that addresses much of what happened in the five-year period 1963-1968 in Cuba. “It is a civil epic,” said the Colombian writer Marco Tulio Aguilera. It took me a lot of work to write it. I took the draft to Mexico in 1995 and left a copy safe at a friend’s house. I wrote it with pieces of typewriter ribbon, with stolen paper, sometimes recyclable—including carbon paper—and sometimes with hunger. The draft—the first version—was written from 1990 to 1995. Then I worked on it a lot and didn’t want to rush to publish it; They warned me that it wouldn’t be easy (I had 700 pages) and I decided to prioritize “A wounded deer”.

And what about A Wounded Deer? What relationship did you have with the UMAP?

I was there for 6 months in 1966. They discharged me because I was the sole breadwinner of the family and the law had been violated in my case. In my novel I base myself on my experiences and testimonies of those who had come before me. That was terrible. Just taking a mother’s child away from her without telling her where they are taking him is vile enough. Last October we turned 60 years old. of the establishment of the UMAP. There were young people and not so young people—there were those 40 years old and older—whose only “crimes” would be belonging to a religious denomination, being homosexual, living in what they called the “sweet life” or in some way being opposed to the regime.

Why are sex and eroticism always present in your narrative?

And sometimes also in my poetry. “Style is the man,” said Georges-Louis Leclerc. And I think that’s how it is. Each writer must have a voice and a world—of course I’m not referring to a physical world—if they leave for some reason, for money, to be cool, to obey any external factor, etc., they’re screwed.

Which of your novels do you prefer?

“In your white dress”, “The heart of the King”, “A madman can”, “A wounded deer”, “Irene and Teresa” are one of the best things I have ever written.

You lived in Mexico and acquired citizenship of that country. What did Mexico mean to you?

I lived for 20 years in Mexico City, from May 31, 1995 to June 11, 2015. I went for a week for a cultural meeting, a week that lasted 20 years… The blood of tequila It has a high autobiographical component. For me, Mexico meant a reunion with life, another birth, the resurrection… But, in any case, it is terrible to be far from the earth, and even more so for those who are very attached to it, as is my case.

After 5 months of being in Mexico I began to write “A wounded deer” and the poems that make up “The country is an orange”; Then, I continued with the—arduous—work of “The King’s Heart.” And I have continued writing until today. Which is difficult when you have “given up” on your resume, and on the readers of your country, as is the obligatory case of the majority of Cuban writers who emigrate.

One of your collections of poems is titled “The homeland is an orange”… How has being outside of Cuba affected you?

“The country is an orange” contains a lot of sadness; I wrote several of his poems almost tearing up. As I told you, abandoning the land, the family, is something terrible. Today I can affirm that with a lot of personal effort and with what they call the soul in strips, I survived.

What is the next book you have in store for us?

I recently published “Tania”, a short novel that takes place in Ciudad from Mexico. My three most recent books—we shouldn’t say “the last”—are set in Mexico City. Now, I’m working on a book of stories that also take place there. These are stories, not short stories, because there are differences: the story can take on subplots and several characters who in turn are more elaborate, more complete than in the story, and therefore is more extensive. Let’s say that the story is the man who crosses the street from sidewalk to sidewalk, and the story is the same man who crosses the street, enters the park, walks around, greets a friend who tells him about his tragedy and meets a woman and a whole story explodes with norths and souths and pasts and futures. The working title is “I DON’T WANT YOU TO GO” — “Eight real-life love stories in Mexico City.” Likewise, I am working on a collection of poems that will be titled (I hope to have the fuel to finish it): “At the Age of Dying.”