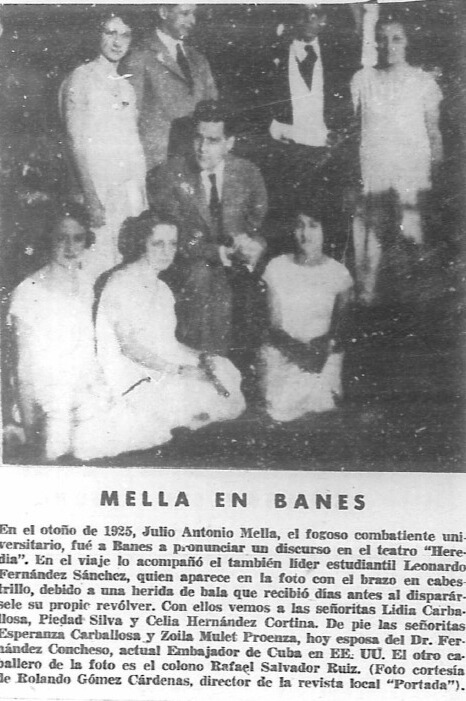

Whistling death comes. Two treacherous shots burn the cold night of January 10, 1929 in the capital of Mexico. The wounded man still has time to shout his denunciation: “Machado ordered me to kill,” and already in the arms of his beloved he exhales dramatically: “I die for the Revolution…Tina, I die.” Julio Antonio Mella died in the early hours of the 11th, on the operating table at the Red Cross hospital.

The press sold it as one of the most sensational attacks of those times. But what few know is that he could have died earlier, at just 21 years old, in an accidental episode that occurred in the eastern town of Banes. The most curious thing is that it would have been a helping hand.

In the land of “Mamita Yunai”

Located on the northern bank of Oriente and small as a handkerchief, the municipality of Banes—founded in 1910—seems like a delightful and peaceful corner; It gives the feeling of a sanatorium or place of retreat where the light of day comes and licks the rose bushes in the gardens. Banes is a hacienda of sturdy wooden chalets, with doorways where silence and dream swing, sheltered by wicker rocking chairs and honeysuckle bowers; of sanded streets where muted footsteps are muffled and people pass by leaving footprints.

On the opposite side of the postcard is the corporate and industrious Banes, that of the shops, hotels and factories, of the dock in the bay, of the Pasaje mail-train, of the marginalized neighborhoods and the Jamaican laborers giving mocha incessantly; In short, everything that constitutes life in a provincial village in the 1920s between the barbed wire fences of the United Fruit Company. The region also moves and shakes by the tide of its political passions, union demands and fights for social demands.

On February 23, 1925, traveling through monotonous cane fields and Johnson banana fields, Mella arrived in Banes. It is not just any hamlet on the map, but the fiefdom of the United Fruit Company, the “Mamita Yunai” some call it in a desire for gossip. The powerful emporium of oligarchs with offices in Boston controls many of the best lands in the country, where they plunder resources without asking permission and subjugate their populations with implacable ferocity.

Mella spends the next four days there. With his feet on the line, he becomes convinced that the theories he has studied extensively and the stories he has heard from unionists become a tragic reality in that place. He has collided head-on with the monster that Martí had warned about. He receives a brutal lesson from the Cuban panorama and turns it into an incentive for future battles. From experiences like that his stature as a continental idol was forged.

The rower from the University of Havana, with his tall and Apollonian build like a Greek statue with dark skin, dark hair, a profiled nose, penetrating gaze and eloquent lips, draws a legion of female admirers in the small country town. It also impresses men. “He seemed jovial and sociable at the same time as energetic. In short, physically we found him a vigorous personality that denoted possessing talent and courage, magnificent qualities to lead a people,” subscribed the communist fighter Delfín Mercadé Pupo (BohemiaJanuary 17, 1969).

Little has been said about the presence of the youth leader in towns in deep Cuba, except for his visits to San Antonio de los Baños and Cárdenas, motivated by the arrival at that port of the first Soviet ship that anchored on the island. However, as part of his revolutionary dynamic, Mella made a pilgrimage at full steam through the mountains and cities defending the sovereignty of the Isle of Pines against the Hay-Quesada Treaty, rejecting the Platt Amendment, rallying opposition sectors against the surrendering and corrupt politicking.

Precisely a conjunction of the so-called living classes, leftist forces and the Veterans and Patriots Movement, invited Mella, Rubén Martínez Villena and other founders of the Anti-Imperialist League, to participate in a commemorative event in Banes for the anniversary of the restart of the wars for independence.

What is it about, what is it about… the rally

On February 24, the town dawns dedicated to joy and the celebration of its popular festivities. The grandiose rally has been arranged for ten in the morning on the esplanade of the bridge that simultaneously unites and divides urbanity into two contrasting wings, the “American neighborhood,” residential and elegant, and “the town,” with its humble houses and battered streets. According to the program, Mella, Villena, Leonardo Fernández Sánchez and Mariblanca Sabas would speak. But the forces of power were not going to be simple spectators, nor would the script be fulfilled to the letter. In the end, of all of them, only Mella could speak.

One of the figures summoned was the journalist and feminist Mariblanca Sabas Alomá. He had met Mella in 1923, having recently arrived in Havana from his native Santiago. From that moment on, they established a fruitful relationship of friendship and collaboration, which led them to travel together to the territory of Holguín.

In a text of his signature published by Bohemia (December 4, 1964) Mariblanca relates: “When we arrived in Banes, an impressive crowd accompanied us to the theater. Already in its premises, barely being able to move among a mass of people who were deliriously acclaiming Mella, there was tremendous confusion. Access to the stage was prohibited to us by the municipal mayor in person with several law enforcement agents. The consul of the United States was present. In a display of cynicism and abjection that “It filled us all with indignation and anger, the mayor told us that the event could not be held, because the American consul had prohibited it. The blood that began to circulate through our veins was fiery.”

The Rural Guard goes into sabotage action. There are shouts, shots, running and running… A good part of the people resists in their firm intention to carry out the demonstration, until the soldiers end up violently dissolving the crowd. Given the context of confrontations, the promoters rush to declare the event concluded, but the angry mass is not satisfied. The rally, now under the sponsorship of the Workers’ Union – which at that time was in a dispute with the United – is once again set for the 27th. Seasoned in the tangana, Mella and company make a clear decision: the event will take place, in any case… “To the public square!”, they shout. Domínguez Park is chosen, the most popular at the time.

For the occasion, an arch is erected with a giant sign: ISLA DE PINOS CUBANA, and the stage is filled with flags and posters with patriotic slogans. Led by Emiliano Varona Mollet, the Company’s carpenters form the platform in record time from which the fiery speaker has to flog magnates and exploiters. Painted in yellow, white and light blue, with a three-word sign in black: “Unión Obrera”, in a semicircle, and below “Banes”, it would be called “Mella’s tribune” and preserved as a relic of the proletarian federation, then by the Veterans Center, until in 1982 it was transferred to the newly founded Municipal Museum.

The rally is tremendous. The witnesses’ assessments agree that Mella gave a formidable speech. “Someday we will paint red that neighborhood of the United Fruit Company workers, whose houses the Yankees have painted yellow like the uniforms of the army henchmen,” he said in a sententious voice.

Exception witnesses

From the trunk of her retinas, Caridad Proenza would take: “Julio Antonio Mella arrived in the afternoon with a colleague who was also quite remembered in Cuba, Leonardo Fernández Sánchez. All the students welcomed him there and we were enthusiastic, we knew about the things he had done and his anti-imperialist attitude. All the people came to the rally. One of my aunts very much remembered a phrase that was recorded in her, because he spoke so expressively, so that the people would understand the things. He said: ‘We change our way of being and we have to change Cuban politics because no one can go back to wearing the shirt they were given the day they were born, because it no longer serves them. So in politics it is no longer useful to us and we have to move forward.’ The people were really fascinated by his words.”

In his account—compiled in Nick: 100 yearsby Ana Cairo—added Caridad: “All of us young people who started high school went everywhere with him: to the gardens, to the fountains. When we were doing the tour we stopped to look at the highlands of Holguín and he said: ‘Where I want to go is that mountain’. He was very interested in everything. He had great magnetism.”

Another teenager who felt like he was struck by lightning was Juan Blanco. Being already a veteran, this is what he told researcher Joel James, who included it in his text Voodoo in Cuba: “Perhaps my life as a revolutionary began that distant day in 1925 when I heard Julio Antonio Mella, in the town of Banes, denounce the imperialist penetration into our country.”

In detail he continued: “I remember his athletic figure, his fiery eyes, his accurate word when he also condemned the mistreatment given to Haitian immigrants, chained by the wrists and taken like this, in freight cars, to the barracks, where they were treated like slaves.”

Likewise, on that tour Mella founded a classroom-subsidiary of the “José Martí” Popular University at the headquarters of the Workers’ Union; He toured bateyes preaching Marxist ideology and the meaning of the working class; invited by Peppon Pérez Sanjuán went to eat roast pig at a farm in the Mulas neighborhood; accompanied by Mariblanca, he attended a festival to raise funds; It fostered alliances between workers, peasants and students. His revolutionary avant-garde harangue won over people from Banes, Antilla and Mayarí.

A little more and…

But the story could have been different. Mella spent Banes’ days staying in a hotel where he shared a room with Leonardo Fernández Sánchez, his friend and president of the Student Association of the Secondary School of Havana.

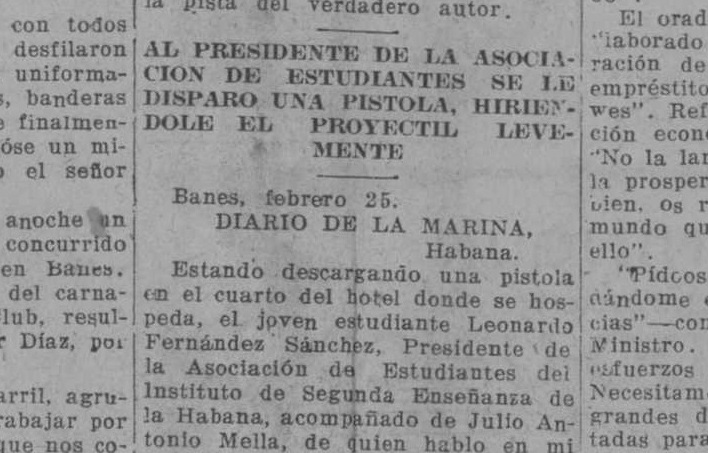

Before going out into the street, on the morning of February 25, Fernández decided to “sharpen” his pistol. Cleaning it is an act of apparent simplicity, as is customary. He takes out the comb, but is unaware that a friend to whom he previously lent the gun has left a bullet directly in the barrel, and has returned it to him without due warning. Confident, the young student brushes the trigger in his handling and the shot escapes. The projectile passes through his left hand and passes near the head of Julio Antonio, who is sleeping next to him.

He wakes up from the shot. He has miraculously survived. That night, as if nothing had happened, he will go to the workers’ center to present his conference “Man and the social revolution.” From the opposite sidewalk, the correspondent of the Navy Diary pointed out that this allegation “was extremely radical, involving in its derogatory censures […] to the Catholic Church, to the nobility and to everything that represents the foundations of the social order.” The letter closed by criticizing the organizing committee for including in the day of local celebrations that “kind of propaganda paid for with money collected from the people.”

With its lethal whistle, death has just stung too close and Mella practically doesn’t even flinch. He is about to turn 22—he was born on March 25, 1903—and he is already a man of complete fiber and astonishing serenity, made for feats that seem unrealizable. Looking at the bloody hand of his comrade—although the wound is not serious and in reality Fernández will only regret not intervening in the rally and spending a few hours in detention—Julio Antonio Mella only manages to comment as if he were stretching: “A little more and the revolution ends here.”