For mine, for my compatriots, for my Cuba. For what is coming.

On the threshold of a new year I don’t ask for too much: just a little certainty. Not as a slogan or as a promise, but as a minimum condition for living with meaning. Because if something has been eroding over the years, it is not just the economy or material expectations, but that intimate confidence—silent but decisive—that the country and its children will be better tomorrow than today.

Certainty is neither a philosophical abstraction nor a privilege. It is a concrete tool of everyday life. It is the base from which you can project, resist, create and even dissent. When that certainty breaks, it is not just doubt that appears: fatigue, disaffection and the temptation to withdraw emerge. Life begins to be lived in a transitory key, as if everything were provisional, as if nothing had ever taken root.

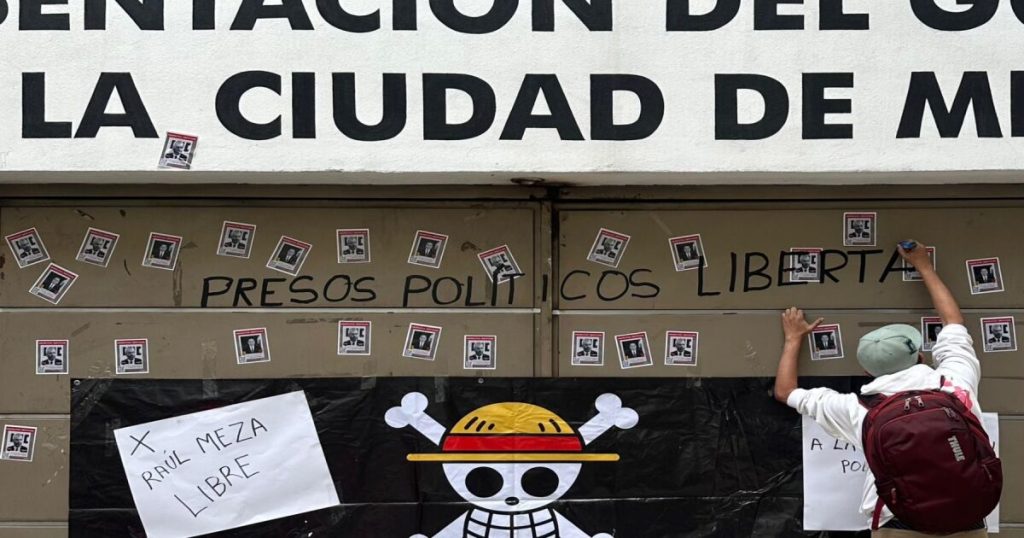

Hence the question is inevitable: how long has it been since we had a certainty quota? Since when has living in Cuba become more like managing uncertainty than building a horizon? These are not absolute guarantees or idyllic futures, but rather something more basic: the possibility of imagining tomorrow without the constant feeling of fragility. The lack of certainty is not only economic; It is also existential. It infiltrates family conversations, decisions that are postponed, silences that last. It is a form of subjective wear and tear that is rarely reflected in statistics.

Exactly twenty years ago, in the midst of readjustment after the crisis of the Special Period, Fernando Martínez Heredia warned about this crucial point. In his essay “Nation and Society in Cuba”, included in In the oven of the 90spointed out that it would be ineffective to confront the cultural war of contemporary capitalism solely from the convictions and experiences of a past of already formed struggles, achievements and identities. That world, he maintained, contained essential values to face the challenges of the present, but it also showed signs of exhaustion and moral weaknesses that made it vulnerable. The hegemonic culture did not advance as a restoration of a defeated past, but as a promise of progress, as a necessary adaptation, as an inevitable future.

Towards the end of that text, Martínez Heredia formulated an even more demanding warning: before the Cubans, a stage of cultural struggle was opening up in which resistance would not be enough. It would be necessary to be creative to move forward without losing the nation or the most just and human way of life conquered. And he added a central idea, almost forgotten today: the urgency of a renewal of the revolutionary project that integrated the harshness of current realities with more ambitious objectives than those of 1959.

Two decades later, when no one can deny the bleeding of the myth, that reflection retains a disturbing validity. Not only because the global context has become more aggressive, but because the absence of internal certainty weakens society’s ability to produce meaning, imagine alternatives and sustain ties. Without renewal, memory risks becoming ritual; Without a horizon, identity tends to retreat.

On the other hand, certainty is not obedience or blind faith. It’s coherence. It is the trust that is built when there is correspondence between the discourse and the lived experience. It is the point at which ideas stop being abstract statements and become social practice. When that coherence breaks down, what is eroded is not only institutional credibility, but also people’s emotional relationship with the common project.

That is why certainty is not decreed or imposed. It is not born from repeated slogans or self-sufficient stories. It is built in concrete life: in sustained policies, in the real possibility of participating, of being heard, of not feeling administered as collateral damage. In sociocultural terms, it is built when the nation once again becomes a space of shared meaning and not only a symbolic framework.

Talking about the future, then, requires something more than promises. It requires political imagination, public ethics and a genuine willingness to review what has been inherited. No emancipatory project can be sustained indefinitely only on the epic of origin. When the revolution stops questioning itself, it also stops revolutionizing.

Perhaps the certainty to which Professor Martínez Heredia alluded is nothing other than the possibility of rethinking the country from creativity, not understood as a fragile slogan attached to the idea of resistance, but as a conscious practice aimed at producing meaning, horizon and project. A creativity that does not renounce social justice or dignity, but that assumes, without paralyzing nostalgia, that every form of just life needs to be reviewed and renewed so as not to become exhausted.

For Cuba, today, certainty would be something modest and profound at the same time: feeling that staying is not a naive gesture, that imagining the future is not an empty exercise, that daily life does not take place outdoors… and without light.