The Cuban foreign minister criticizes hatred and violence on social networks, but his regime holds more than 1,000 political prisoners.

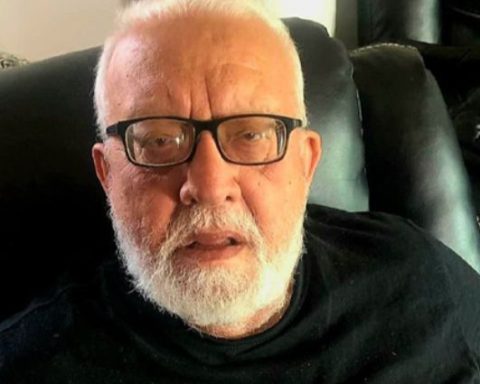

MIAMI, United States. – The chancellor of the Cuban regime, Bruno Rodríguez Parrilla, amplified this Wednesday in X an investigation of the Media Observatory Cubadebate that warns about the “normalization of political hatred” on social networks and its possible lead to violence, while calling on digital platforms to enforce “their own rules with rigor and without double standards.”

In his publication, Rodríguez assured that the study “reviews 230 publications” and that it detected “a relevant weight of actors located in the US, especially in Florida.” He added that, when classifying the messages by severity, the analysis “warns that close to 80% are concentrated in high ranks” and described “repeated patterns”: “calls for physical harm, attacks on infrastructure and ways of ‘operationalizing’ violence (coordination, tactics, anonymity)”, in addition to “sustained mobilization with a confrontational tone.”

The official stressed that “criticism is legitimate”, but that “incitement to violence is not” and maintained that “dehumanization, pointing out and calls for harm are not ‘opinion’, they are a risk to people’s safety.” In this framework, he demanded that the platforms act without “ambiguities” and called to “protect life, coexistence and civilized debate.”

The research to which the chancellor alluded—titled “From insult to violence against Cubans on social platforms”—maintains, as a central thesis, that the “permissiveness” of the platforms and the normalization of coercive language degrade public debate and increase the risk that “symbolic violence” tries to give way to real aggressions.

However, the chancellor’s message contrasts with sustained allegations by human rights organizations about internal political repression in Cuba, including the existence of more than 1,000 prisoners for political reasons. The NGO Prisoners Defenders reported on December 9 a total of “1,192 political prisoners” on the Island, a figure he described as “a new record.”

Against the Cubans, in the networks and in the streets

This discourse also contrasts with the use of the Cuban penal system to punish expressions on social networks that have not led to violent acts. Human rights organizations and independent media have documented multiple convictions for critical publications on Facebook and other platforms, covered by ambiguous criminal figures such as “propaganda against the constitutional order”, “contempt” or “outrage to national symbols”. These processes have been highlighted for their lack of guarantees and for criminalizing the exercise of freedom of expression.

Among the most cited cases is that of Aniette González Garcíasentenced to three years in prison after publishing images on Facebook wrapped in the Cuban flag, a sentence that generated international complaints because it was a symbolic expression without any call to violence. Also were convicted Félix Daniel Pérez Ruiz and Cristhian de Jesús Peña Aguilera were sentenced to five and four years in prison, respectively, for publications on social networks in which they expressed disagreement with the Government and promoted a protest that, according to the court ruling itself, did not materialize.

Independent media such as YucaByte have documented even harsher sentences, including sentences of up to 10 years in prison, supported by digital publications considered “subversive” by the authorities. These cases add to a broader pattern of repression documented by international NGOs and United Nations mechanisms, which have warned about the systematic criminalization of dissent in Cuba.

Last November, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention ruled that 49 9/11 protesters were arbitrarily detained “for political and ideological reasons and without due process,” and urged the Cuban State to release, exonerate and compensate them.

In this context, while Rodríguez demands that platforms sanction “dehumanization” and “calls for harm,” international organizations and UN mechanisms have described patterns of arbitrary detention and rights violations linked to the punishment of protest and dissent within the country, a contrast that makes the official demand for “civilized debate” externally politically significant, when the Cuban State itself is accused of restricting it internally.

Added to these allegations is a broader picture of restrictions on fundamental freedoms within Cuba that international organizations have repeatedly documented. In its most recent country file, Amnesty International holds that in Cuba “freedom of expression was further restricted” and that “arbitrary arrests” and the criminalization of activists, human rights defenders, journalists and protesters persisted, in addition to reporting harassment and mistreatment of detainees.

Human Rights Watch, in his chapter on Cuba World Report 2025also describes a pattern of repression and punishment against “practically all forms of dissidence and public criticism,” in a context of economic crisis that impacts rights such as access to health and food. In a report last July, the organization added testimonies from 9/11 protesters about serious abuses in prison and recalled that, despite releases announced in 2025, “hundreds” remained detained.

In parallel, the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the IACHR (OAS) has denounced state repression in Cuba and has called for an end to measures that affect rights such as freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and protest, with references to surveillance, arrests and other control mechanisms over critical voices.

This backdrop is what makes the chancellor’s demand for the platforms to act with “rigor” against incitement to harm and “dehumanization” especially contradictory, while the Cuban State itself is accused by organizations and NGOs for punishing dissent, restricting civic space and keeping more than a thousand prisoners for political reasons, a scenario that, for its critics, erodes precisely the conditions of “coexistence” and “civilized debate” that the Government claims to defend. on the digital level.