In the midst of increasing restrictions in Donald Trump’s immigration policies, thousands of Cubans today see their dreams of emigrating or remaining in US territory with legal status disappear. On December 3, the United States government immediately suspended all requests for asylum, residence, naturalization and other immigration procedures for citizens of 19 countries—including Cuba—which generated deep and new uncertainties.

The US Administration revoked tens of thousands of visas in 2025 – including student permits – massively and suddenly, increasing the climate of fear and insecurity for those who trusted in the possibility of studying, working or building a life in that country.

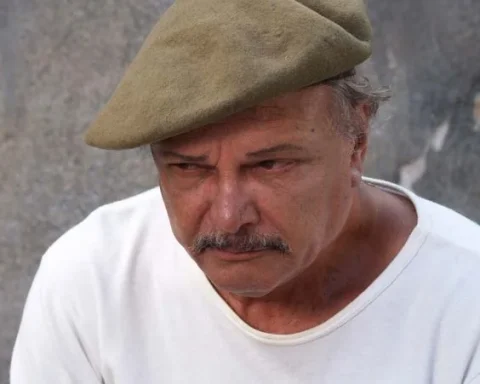

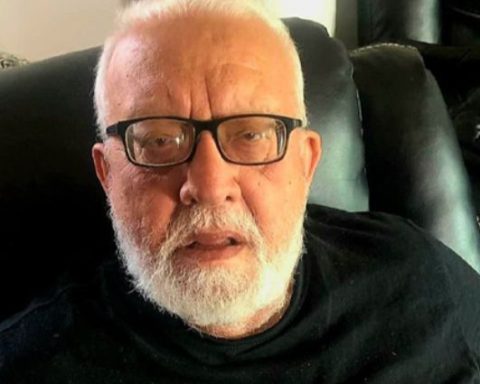

In this context of hostility and uncertain future for many migrants, OnCuba He spoke via WhatsApp with Hedels Gonzálezpsychologist specializing in mental health and migration, and founder of the project “Emigrate inward”.

From his clinical perspective, he analyzes how grief for an imagined future is processed, what happens when life seems to be put on hold, and what are the emotional effects that individuals and communities affected by this reality go through: grief for what was conceived as a future life, the loss of economic resources invested in the journey, and the psychological wear and tear caused by uncertainty due to decisions beyond their control.

Migration is usually experienced as a vital project: a dream, a purpose, sometimes an escape route. What emotional effects does the sudden interruption of that project generate? How do you process grief for lost expectations, for that “imagined future” that suddenly fades away?

The sudden interruption of an immigration project not only cuts a plan: it breaks a narrative of future life. The person did not just imagine a country, he imagined a different version of himself: how he was going to live, work, grow old, take care of his loved ones, what he was going to achieve. When that imagined future falls apart—and I’m not talking about just any life crisis, but rather when you’re told it’s probably not going to happen—a very particular grief is activated.

It is a mourning for something that did not exist, but that was very alive psychologically, because it was the desire that moved the person. Emotionally we see sadness, frustration, rage, anger, helplessness, lack of clarity about the future and a lot of identity confusion: if I am not the person who left, and I don’t know if I will be the one who will return, who am I now? What do I do with everything I started and everything I left?

It is key not to pathologize this response. It is expected that sadness will be intense. It does not mean an inability to face it: it is that the process is enormous and deeply uncertain.

Processing grief does not consist of “turning the page”, but rather integrating it: giving a name to the loss, recognizing the breach of security, accepting that we are in uncertainty and that we will not have an immediate answer. For a time, the task is not to rebuild oneself, but to endure the void left by this impasse, this time determined by external causes.

For many Cubans, emigrating means joining a diaspora that financially supports their families in Cuba, who today depend on that support to overcome the crisis. From your clinical perspective, how does being trapped in a limbo where an external political decision can redefine their entire life project impact the mental health of Cuban migrants?

Lack of definition and bureaucracy are not just annoying administrative procedures within migration, things that we already had normalized and assumed as part of the process. When decisions of this type occur—like what is happening now—what is suspended is not a procedure, it is a way of life. It’s as if we were left at an impasse in time, as if they put life on pause and, from there, we don’t know how to redirect anything.

From the clinic, what we see is that when there is a political decision capable of determining whether your life project continues or collapses, a kind of freezing of psychological time occurs. The person cannot settle where he is, but he cannot go back either. A parenthesis is generated, an emotional freeze, even emotional anesthesia, during a time whose end no one knows.

In the Cuban case this is aggravated because migration is crossed by a transnational responsibility: it not only implies one’s own well-being, but also economically supporting those who stayed. So, when the immigration status is suspended, it not only shakes the life of the person who migrated, but also that of all the people who depend on that project. What is expected? A lot of fear, a lot of guilt and an enormous demand: “I drag my entire family with me.”

Clinically, rather than talking about stress or transitory anxiety, we are talking about structural insecurity: the feeling that, no matter how well you do, no matter how much you organize yourself, there is an external entity that can dismantle everything from one moment to the next. This erodes basic confidence in a stable future and also self-confidence. It’s not just about the control I can exert over my life in this country; A deep doubt sets in about my own ability to sustain it.

It is important to emphasize that this is not individual fragility. Feeling overwhelmed is the logical and expected response to a context that offers no guarantees.

Cubans, Venezuelans, Haitians, among others, have been collectively affected by the massive paralysis of asylum applications; these are not individual or isolated cases. What psychological consequences could such a measure have on entire communities? Is there a risk of stigmatization, social withdrawal or a shared feeling of helplessness?

This was already seen even before the measures were made official. In consultation I have received people who are very afraid, stopping doing basic activities such as going for a walk, shopping or driving, for fear of what is happening politically. When a measure like this hits entire communities, a shared trauma expands: it is not a failed procedure, it is a collective message that says “you, as a group, are a problem.”

This has several layers of psychological impact. On the one hand, the risk of external stigmatization: being seen as a threat or social burden. But self-stigmatization also appears: starting to look at yourself through the narrative that your environment imposes on you. Feelings of not belonging, of not deserving, discomfort in public spaces, isolation, confinement arise.

A subjective but very important feeling is added: shared helplessness, the feeling that no one is protecting the community. As if they were expendable lives for the decisions of the State. All of this generates social withdrawal, emptiness, anger, institutional distrust and a breaking of the link with the State as a protective figure. It is not explained solely with diagnostic labels, but as a response to being treated as less assured lives.

When the immigration privileges that historically existed for Cubans in the United States are blurred, how does that affect emotional well-being? What happens psychologically when that idea of guaranteed welcome is abruptly broken?

For years, many Cubans grew up with the idea that the United States offered an open door, differentiated treatment, an implicit guarantee of welcome. That expectation worked as a psychological engine: “if I get there, I can make a new life; there is a place for me.”

When that expectation is broken or appears to be broken, the impact is twofold. On the one hand, a crisis of confidence towards the country they aspired to reach, which had to guarantee security and stability. On the other hand, a crisis of personal value, because the message received is: “you are not welcome, you represent a risk.”

Psychologically, this can translate into anger, shame, feelings of fraud, betrayal, and the idea that there is no place in the world where you can feel protected. The instability of that expectation sustained over time has an enormous emotional cost.

Many of those who are stranded today in uncertainty sold properties, quit jobs, said goodbye to their families and planned an entire life in the United States. How do you deal with that “void” that remains when the project stops or is postponed indefinitely? What coping strategies and practical tools do you recommend to regain emotional stability and redefine the horizon?

I’m going to be totally honest: in such fracturing external processes, there are not many strategies to deal with, and even less to redefine horizons. It’s like asking someone in the middle of an absolute void to reorganize their entire life.

When an immigration project is abruptly interrupted—a project where there is so much external control—there are no three magic steps to rebuilding. The first thing is not the strategies: the first thing is to name the reality. Name that there are lives broken, families fragmented, projects dismantled, resources invested that may not be recovered.

Talking too soon about redefining horizons can be unfair: it would be asking the person to adapt to something that does not yet exist. In this phase, the task is not to redo, but to go through uncertainty. Accept the emptiness, the discomfort, the unanswered questions, the imagined scenarios because there are no external truths yet.

The context—not individual will—is what will determine the conditions. Therefore, more than reconstruction tools, we now need minimum daily anchors: supporting the body, maintaining small routines that give structure, taking care of what is controllable without demanding miracles.

It is important to have spaces where we can talk about this without minimizing it, sharing with people who understand fear and anxiety. This is not the time to make big decisions. It is time to take care of the stability that exists, plan carefully, contain expenses and accompany our reality without acting as if nothing was happening.

The solution does not depend only on individual resilience. There is an external element weighing heavily. When the context is defined—for better or worse—there will be room to rebuild, to create a new story for the future. But now, the most honest thing is to accompany the wait, legitimize the discomfort and not turn resilience into another obligation.