According to the Reuters agency, Nicolás Maduro presented conditions to leave the country. He follows the tradition of dictators like Marcos Pérez Jiménez and Augusto Pinochet who sought solutions and reached negotiations. Others, like Saddam Hussein, did not achieve their goal. Some, like Oli in Nepal, did not even have time to agree exit deals. La Hora de Venezuela presents an account of the past to analyze future scenarios

Venezuela Time

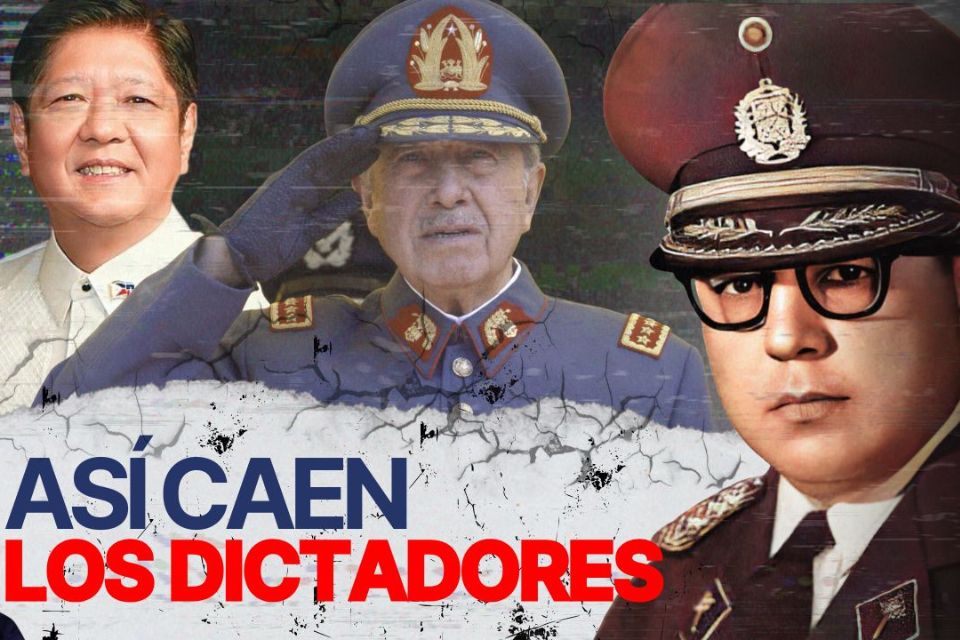

Dictators almost never hand over power out of democratic conviction. They do it when their future—and that of their family—is guaranteed. That has been a historical constant that crosses continents, ideologies and eras. From Marcos Pérez Jiménez in Venezuela to Augusto Pinochet in Chile, passing through Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines, everyone sought to protect themselves before leaving power. Today, that pattern appears again in Venezuela.

According to an investigation by the Reuters agency, Nicolás Maduro presented a set of conditions to leave the leadership of the regime. These include a total amnesty, the lifting of sanctions, the suspension of the investigation by the International Criminal Court and the permanence of Delcy Rodríguez in power as interim president. It is the classic manual of transitions controlled by autocrats, but with an additional element: the continuity of power within their own circle.

History shows that these guarantees are often repeated with almost mechanical precision: immunity from prosecution, safe exile, preservation of assets, protection for family and allies, a comfortable life as a former president and, above all, the certainty that no military force will touch them during the transition. Without such insurance, dictators rarely agree to leave office.

From Pinochet to Chávez

In Chile, Augusto Pinochet handed over power in 1990 after securing eight more years as commander in chief of the Army, lifetime immunity as a senator and protection for his family environment. But his story did not end there. In 1998 he was arrested in London by order of Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón, accused of crimes against humanity. After a lengthy judicial process, the United Kingdom authorized his extradition, but finally allowed his return to Chile for “humanitarian reasons.” Back in his country, he lost his immunity and faced multiple legal proceedings until his death.

In the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos was removed from power in 1986 and transferred with his family to Hawaii under the protection of the United States. That was an outing designed to suit him. Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, in Haiti, went into exile in France with part of his fortune. He believed he had bought impunity, but when he returned in 2011 he was arrested and put on trial.

Others did not have that margin. Saddam Hussein tried to negotiate his way out after the invasion of Iraq, but ended up captured, tried and executed. Nothing he aspired to happened. Muammar Gaddafi offered to agree to his retirement in Libya; Nobody believed him and his end was brutal. Slobodan Milošević, in Yugoslavia, agreed not to be extradited, but his successor broke the agreement and sent him to The Hague. Manuel Noriega, in Panama, spoke with the United States believing that he had guarantees; He spent three decades imprisoned in different countries. Charles Taylor, in Liberia, received asylum in Nigeria with a mansion and escorts, but years later he was handed over to stand trial. Anastasio Somoza Debayle escaped to Paraguay believing himself to be safe and ended up murdered inside his armored car during a Sandinista operation. Robert Mugabe signed an exit pact in Zimbabwe, but it was his own party that ended up removing him from power. Omar al-Bashir, in Sudan, received promises of non-extradition that today hang by a thread before the International Criminal Court.

In Venezuela there was already a direct precedent. Marcos Pérez Jiménez fled in 1958 with guarantees: presidential plane, exile and protection. But in the United States he was arrested, extradited and ended up imprisoned in Venezuela. After regaining his freedom, he won a senatorship, but was not allowed to assume his seat. Then he went to Spain, where he lived the last thirty years of his life. He was never able to return to Venezuela.

There is also the episode of April 2002. According to the version of the military who participated in the momentary overthrow of Hugo Chávez, his retirement to Cuba was negotiated with the then president in exchange for a million-dollar sum. The outcome is known: on April 13, Chávez returned to power and none of that negotiation materialized.

*Also read: Qatar says it is “waiting” for a request to act as mediator between the US and Venezuela

Generation Z

But not all transitions go through pacts. In recent years, scenarios have emerged where the street or military force defined the destiny of power. In Sri Lanka, in 2022, the combination of economic collapse and corruption triggered a wave of protests led by young people from Generation Z, born between 1997 and 2012, digital natives who turned social networks into a tool for political mobilization. Images of young people entering the presidential palace spread around the world. The president fled without negotiating anything.

In Nepal, in September 2025, the government’s blocking of 26 social networks was interpreted by that same generation as a declaration of war. Thousands of young people took to the streets. The repression left dozens dead and hundreds injured. Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli ended up resigning. Not only a government fell there, but an old way of exercising power.

In Syria, after 13 years of civil war that began in 2011, the transition did not come from the streets or from a political agreement. It was pure force. In 2024 an armed coalition advanced on Damascus. The regime collapsed in a matter of days. Bashar al-Assad fled to Moscow with his family. There was no negotiation or guarantees.

In this context, Maduro’s demands fit precisely into the historical pattern of dictators seeking to shield themselves before giving in. According to Reuters, what he proposes includes amnesty, lifting of sanctions, suspension of the case in the International Criminal Court and the preservation of power within his circle. For Donald Trump, accepting an exit without military force would imply a political victory without war or costs in American lives. But the knot is in the intention to leave Delcy Rodríguez in Miraflores.

Mature the unfulfilled

Tensions have increased. Senator Marco Rubio warned this week that Maduro has broken at least five agreements in ten years. Washington doesn’t trust his word. And Rubio was direct: Trump will not be fooled by Maduro as, in his opinion, Joe Biden’s administration did.

The outcome does not depend only on international negotiations. History teaches that dictators rely on two pillars: their inner circle and their armed forces. Mature too. However, the Armed Forces have been subjected for years to mechanisms of internal espionage, counterintelligence and surveillance with foreign advice. Despite this, on July 28, according to multiple sources, the majority of the military voted against Maduro. That silent break is reminiscent of the case of Duvalier in Haiti: a dictator convinced that his army was with him, until he stopped doing so.

The analyst and representative of dissident Chavismo Sergio Sánchez recently summed it up on the La Conversa program with a direct phrase: “Maduro must be removed from his trench.” A trench made of sanctions, fear of international justice and absolute distrust in any agreement.

That is why the Venezuelan scenario is complex. Without real incentives to reduce the fear of losing everything—including freedom or life—Maduro will avoid leaving power to the extent he can. History shows that negotiated solutions are not built with desires, but with guarantees. And that dictators do not evaluate constitutions, they evaluate their personal security, that of their family and that of their fortune.

Venezuela has entered that decisive moment. The coming weeks will tell if Maduro gets the guarantees he demands or if political, economic and military pressure pushes him towards another outcome. Because, in the end, transitions are not decided by promises, but by guarantees.

*Journalism in Venezuela is carried out in a hostile environment for the press with dozens of legal instruments in place to punish the word, especially the laws “against hate”, “against fascism” and “against the blockade.” This content was written taking into consideration the threats and limits that, consequently, have been imposed on the dissemination of information from within the country.

Post Views: 239