Matanzas/As soon as the sun warms the pavement in front of the Faustino Pérez hospital, in Matanzas, the sidewalk begins to fill with medical students, relatives of patients and curious onlookers who hang around the blue and red kiosks lined up on the avenue. The scene is typical: a small hive where the smell of freshly made pizzas, the noise of motorcycle taxis waiting for customers and the conversations of those looking for something to eat mix… or something much more urgent.

Sandra is one of them. After hours trying to get the paracetamol tablets that were prescribed for his joint discomfort from the hospital pharmacy, he came up empty-handed. This Thursday she is seen among the kiosks, adjusting her bag on her shoulder, breathing with exhaustion. “They are only giving some of the medications to the admitted patients,” he comments without imagining that, next to a juice and fried food counter, he would find the solution that the public health system could not provide.

In one of those stands, barely noticeable behind the sign for smoothies and pizzas, an employee holds a large bag where soft drinks coexist with bottles of pills, blister packs and several packages of syringes. “She has vitamin complexes, antibiotics and even needles,” says Sandra, while showing the bag with the 500 mg paracetamol that she just bought for 900 pesos. “If I don’t do it this way, the pain will kill me. That’s why the government pharmacies are empty, because there is no one to control this clandestine sale.”

/ 14ymedio

Sandra also needs Captopril for her mother, who has not been able to purchase it at the state pharmacy for more than six months. “I don’t have enough money to pay the 350 pesos it costs right there, if I hadn’t bought it.”

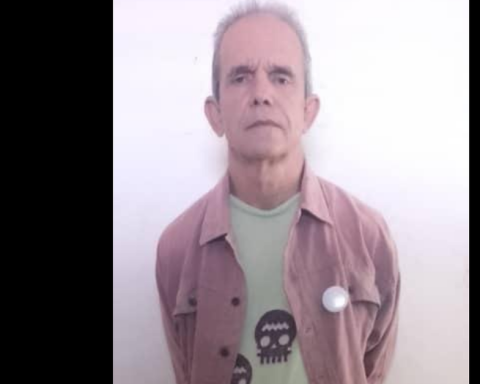

“Together with a malt I paid for the suture thread for my wife’s operation,” says Leonardo, a man from Matanzas who knows the informal circuit well. “The surgeon himself told me where I should go and who I should see.” His words surprise no one: many in that area have gone through the same thing. “Except for the blood for the surgery, I had to buy everything else outside here. Between breads and jams, if you have the money, anything will appear.”

The total cost of supplies for his wife’s surgery was around 5,000 pesos: six pairs of disposable gloves – “at 250 pesos each, sold by a guy who makes bread with fish minutes” –, more antibiotics, more saline solutions, more sutures. “The last straw,” he says, “after being operated on, my wife had a fever. Since there was no thermometer in the room, I came straight here and bought one for 2,300 pesos.”

/ 14ymedio

Laura, a third-year medical student, takes advantage of a break between shifts to get Amoxicillin, which her father urgently needs. The young woman, in her white coat, is chatting with other students and carrying a folded bill between her fingers. “I’m going to wait for a few people to leave. I already know who sells it. I always check the expiration date before buying,” he says.

She herself details what moves in those kiosks: “You can find aspirin made in Cuba as well as antidepressants with a United States label.” Nothing appears on the tablets: neither Loratadine, nor Cephalexin, nor Rosefin, but everyone knows that they are available… at the price of the day. “Medicines cost the same or more than food. Many come to eat a pizza and end up buying pills. It’s an option.”

As Laura discreetly walks away, more students arrive, more family members wait, more vendors arrange boxes or discreetly search inside their backpacks. Between pizzas, soft drinks and endless lines, there is everything that state pharmacies cannot offer.