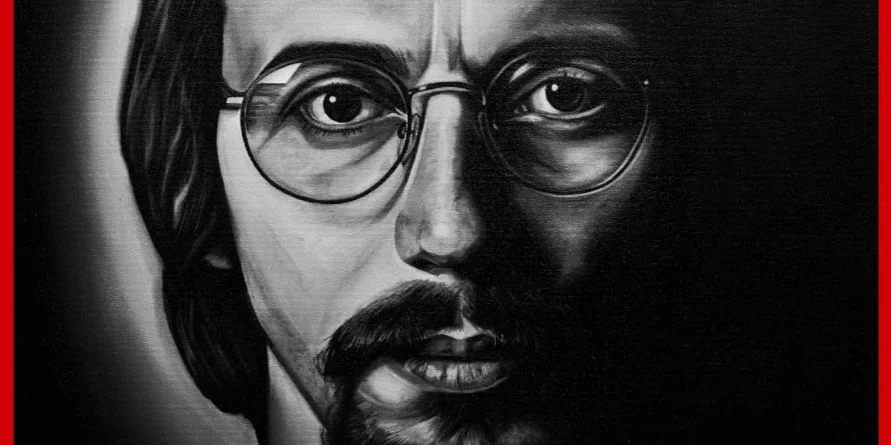

MIAMI, United States. – In an extensive conversation with the magazine Rolling Stone (In Spanish)published this Tuesday, the Cuban singer-songwriter Silvio Rodríguez defended the historical relevance of the revolutions, denied having lost faith in the Cuban one and blamed the global “military-industrial complex” for aggravating contemporary wars and suffering.

“Revolutions are not perfect, they are necessary. Those who make them are human beings like you and me, who are not perfect, so, in one area of the revolution, you see that wonders happen and in another they are doing nonsense.” [risas]“He told journalist Diego Ortiz.

Questioned about possible disappointments, he was blunt: “I have never felt disillusioned with the revolution, ever. Disillusioned with some people, yes, of course. And not even disillusioned, but simply: ‘What’s wrong with this guy?’ [risas]. ‘What’s wrong with this guy?’”

Rodríguez contrasted criticism of capitalism with reservations about socialism as a concrete practice: “Since there is no perfect government, nor is there a perfect system, they are all nonsense. In specific things, capitalism is the exploitation of man by man, but socialism is that thing that wants to put you in a grid and from there it does not get you out…”, he said, before maintaining that in Cuba they tried to “do their own thing” in adverse conditions: “Cuba is a country that has been, rather than blocked, I would say tortured. “He has been subjected to very conscious, intentionally perverse torture by a decaying but extraordinarily powerful empire.”

The troubadour defended the Cuban military deployment in Africa in the 70s and rejected Cuba acting as an invading power. “I am not from a country, fortunately, that sends troops anywhere to invade, to keep the oil, to bomb. Cuba has never done that. Here wearing a military uniform is defense, it is to defend ourselves,” he assured.

In his story about Angola, he emphasized that “Neto [Agostinho Neto, el primer presidente de Angola] He asked Fidel to please send him people so he could fight the South African Army” and described the popular response at that time: “You would go through any Military Committee and you would see two or three blocks of queues of people… of ordinary citizens queuing to go fight in Angola.”

The troubadour did not specify that the young Cubans who completed “internationalist mission in Angola” ―as the regime defines the military operation Carlota―, they were forced to participate in the armed conflict; nor that those who refused were segregated by the island’s regime, which denied them employment and other rights.

Regarding current conflicts, Silvio Rodríguez described the situation in Palestine as a “human shame.” “That is a shame, a human shame,” he said, to link with a repeated criticism of those who profit from war: “We must return to that Eisenhower speech, we must fight the arms manufacturers… Those things do motivate me and they do piss me off, pardon the word.”

Regarding the Russian invasion of Ukraine, he distanced himself, although he introduced his own reading of the conflict: “I do not approve of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, no, I am not justifying that. Ukraine was part of Russia for many years, half of Ukraine speaks Russian. And the Ukrainian reactionaries who took power were bombing all of that Russian part, they had been falling to it for two years. bombing all those people and forcing them to flee.”

The musician was skeptical when asked about the “recipe” that intellectuals should follow: “I am bad at recipes, I don’t believe in recipes. Let everyone be as they want to be. That is the true recipe, that is the truth of life. We are all products of our circumstances, all of us, without exception.” In that thread, he recovered Martí: “True people chose, instead of what was best for them, what they considered correct… I fell for the star that illuminates and kills.”

One of the most revealing passages—for what it suggests about the Cuban cultural ecosystem—was his testimony of media censorship at the beginning of his career. “One day, due to an argument, they took me off television, off the radio, they erased me from national radio. It was forbidden to play my songs.” Even so, he insisted on separating people from processes: “This man is not the Revolution, and there is no one who can throw me out of the Revolution. They can throw me out of a place, but there is no one to throw me out of my country, and from the desire to improve my country, there is no one to throw me away… What is more important: me or what is happening in Cuba?”

Asked about his connection with awards and the industry, he said that the Latin Grammy offered him the award for Musical Excellence, but did not specify the ceremony: “They invited me to give me a Grammy for Musical Excellence (…), but I was very involved in the thing of concerts in the neighborhoods (…) and I asked them if they could give me the Grammy at a neighborhood concert; I invited them to They came to Cuba for that, and they told me no, that it was a mess for them (…). They gave me all those explanations, and that I had to go to Las Vegas (…). They took me into account that time, and it’s good to know that we simply couldn’t meet,” he explained.

In the field of song as a critical tool, he vindicated the tradition of protest—from Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie to Violeta Parra—and his landing on the Island amid external aggression and mass literacy. “Those of us who started playing the guitar and making songs also had that in mind, the awareness that we were singing for a people that already had a certain level of education, it was not an illiterate people,” he noted.

However, in the extensive interview he never mentions Celia Cruz nor to other Cuban musicians forced into exile by the regime. On several occasions he refers to Pablo Milanés like his companion in the Nueva Trova movement, but he does not mention the musician’s break with the regime and with himself.

Although the interview reviews anecdotes from the artistic workshop, literary influences and collaborations, the backbone of the conversation is political and ethical: a defense of the revolutionary project with an admission of “nonsense”, the denunciation of the business of war, a forceful statement on Palestine and a justification of the Cuban file in Angola. Already in a self-referential key, he closed with his method: doubt and questions before certainties. “What are answers for? To ask new questions, that’s what they’re for, they’re not for anything else.”