By Juan Carlos Espinosa

It is difficult, if not practically impossible, to find a resident of Perico (60 thousand inhabitants, 170 kilometers southeast of Havana) who does not know someone who has recently suffered from chikungunya.

“On my block, almost everyone has had it,” is usually the response when residents talk about “that virus.”

In July, this municipality in the western province of Matanzas It was the first outbreak in Cuba of an outbreak that already represents a “national” problem with “high rates,” as health authorities recognized this week.

At first glance, the narrow streets of Perico, with its terraced houses, give an image of normality. Until the small details flourish: like people’s limp or others’ difficulty doing simple tasks like sitting.

Pedro Arturo Revilla, 66 years old, is one of them. He suffered the disease, as did “his entire family,” he says. He still suffers from the after-effects weeks later, such as intense joint pain and swelling in his ankles.

Next to her doorway, a 67-year-old diabetic and hypertensive woman interrupts the interview when she finds out that her neighbor is talking about chikungunya.

“There is no fumigation here, which is why there should have been, with the number of mosquitoes that were here and with the number of sick people there were. Here they do nothing,” he says.

New disease

Chikungunya—which had not been present on the island for a decade—has joined dengue and oropouche, the former transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito and the third by the midge, in a perfect cocktail.

The outbreak has hit the country in the midst of a deep economic crisis, with a greatly reduced capacity to deal with diseases, their vectors and mosquito breeding sites, especially water leaks or liquids that accumulate in mountains of garbage that are not collected for weeks.

In an interview this week for state television, Carilda Peña García, vice minister of Public Health, regretted that massive fumigations cannot be carried out due to the fuel shortage in the country. However, I do assure that the Government has enough “insecticides” and “killers” to limit the damage.

He also stated that, unlike dengue, chikungunya is not a deadly threat, although it could worsen in patients with a previous health problem.

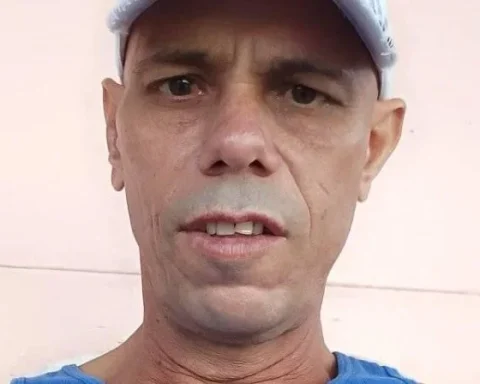

Raúl González, 63, has multiple sclerosis and went through chikungunya. While showing EFE his swollen ankles full of sores, he cracks a critical joke about the situation: “They should make another version of Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’. The extras are going to be free; everyone was walking like a zombie in the street.”

He, like many others, understands that the crisis has made the Government’s response a chimera. But he was furious at the way in which, in his opinion, the state media tried to downplay the seriousness of the matter.

“Apart from not saying what we really have… like everything is normal and there is nothing normal here. We have serious problems, and everyone knows that. The unhealthiness, the garbage that they don’t come to pick up… Of course there are mosquitoes if they don’t fumigate! It makes me angry that they tell lies,” he says.

To date, there is no updated public data on patients with chikungunya (present in eight of 15 provinces), dengue (active in 12 provinces) or oropouche in Cuba (also in 12).

According to authorities, in 2025 three people diagnosed with dengue have died.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a travel alert update at the end of September due to the presence of chikungunya in Cuba.

“It’s horrible, horrible”

About 55 kilometers from Perico, in the municipality of Cárdenas, the situation is very similar. For Beatriz Aguiar, 64, the outbreak “got out of Public Health’s hands.”

Although the authorities have insisted that the health system is not even close to collapsing and that it has the capacity to face the situation, Aguiar saw something different: “You arrive at the hospital and the same doctors say that the daily cases that arrive are horrible, horrible.”

The reality, as a dozen residents between both municipalities told EFE, many infected people self-diagnose and pass the disease at home.

Matanzas intensifies the fight against dengue with reinforcement of resources and medical students

Partly because the first hours of chikungunya are so hard that they leave the infected person bedridden. And also because, they insist, it is of little use to go to a consultation because the doctor will limit himself to making the diagnosis by observation – in the absence of tests – to send them home to take medicines that can only be obtained on the black market and at exorbitant prices.

“It’s really not the authorities’ fault that they don’t know the real figures. But why are you going to go (to the doctor)? To get a paracetamol every four hours, fluids and rest? There are many people who can’t buy even a blister of paracetamol, because it costs 500 pesos ($4, at the official exchange rate; the average salary is about $54 at that same exchange rate),” says Eneida Rodrígues, a resident of Cárdenas about 60 years old.