By Dolores Fernandez Perez, University of Castilla-La Mancha

We live in a society that rewards audacity and coldness. We see it in series like House of Cardswhere Frank Underwood ascends by stepping on whoever is needed. In SuccessionLogan Roy dominates his family empire through fear and control. Even in The Wolf of Wall Street excess is celebrated as if it were genius.

These stories have not invented anything: they reflect a widespread idea, that “the end justifies the means.” And that same way of acting also appears, sometimes, in real life.

Psychopathy has been studied for decades. In the forties was described such as superficial charm, lack of guilt, emotional coldness and impulsive behavior. Later, tools were created to measure it and it was shown that these traits do not only appear in criminals. They are also present, to a lesser degree, in apparently normal and successful people. Some function well in society and are even capable of achieving power.

Profiles that are difficult to detect

However, these types of dark profiles are difficult to detect. They usually live with good social skills. So their initial charm can hide their flaws and their harmful and dangerous behavior. In the short term they may seem like ideal leaders, but in the long term they leave conflict, fear and burnout.

In companies, especially at the top, cold charisma, a taste for risk and manipulation can sell good leadership. Many companies pursue immediate results, apparent security, firm gestures, quick decisions. Empathy, on the other hand, is seen as a weakness. Even in interviews, a person’s poise is valued more than their ethics.

This is how well-polished masks slip in, an appearance of control that can dazzle and hide signs of abuse or incompetence. Then, that coldness and ambition drive the rise, although they often end up weakening the environment that supports them.

Two great psychopaths

Recent history leaves us clear examples. Bernie Madoff He maintained an image of respectability for years while running a huge pyramid scheme that lost thousands of investors $50 billion. Madoff used money coming in from new clients to pay old clients and make them believe they were earning returns. In reality, there was no investment behind it, it was just moving money from one to another until everything collapsed.

Enron’s Kenneth Lay seemed a visionary as his company cooked up accounts and hid debts, until it caused one of the biggest bankruptcies in history and ruin thousands of people. Both showed charisma and coolness until everything collapsed.

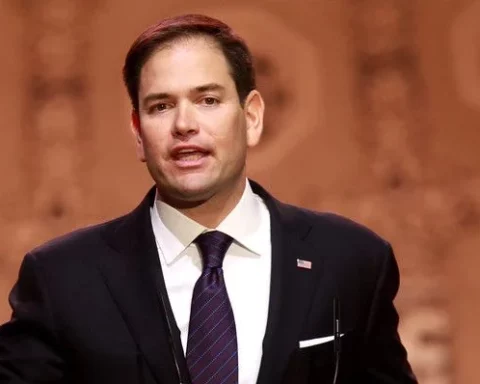

Similar situations occur in politics. Donald Trump has built his image around strength and constant confrontation. Use simple and combative messages, dominate the scene and show no doubts. This inspires admiration for many followers, despite his aggressive tone and his lack of willingness to dialogue and consensus.

Something similar happens with leaders who promote current wars. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or Israel’s offensive in Gaza, with tens of thousands of civilians killed and displaced and a genocide case before the International Court of Justice, show how cold decisions can destroy thousands of civilian lives. Those who suffer the most from these wars are rarely the ones who start them. And yet, those responsible are often revered as symbols of strength.

The “dark triad” and power

Psychologists seek to understand why these types of personalities thrive. It talks about the “dark triad”: narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy. Combined, they convey confidence, dominance and resistance to stress. This can help achieve power, but it carries risks. This meta-analysis shows something important: such traits help get to the top, but they do not guarantee effectiveness once there. Some leaders achieve short-term results; others sink the morale of their teams and make reckless decisions. A little boldness helps in a time of crisis. But an excess of it breaks trust and ethics.

There are traits that can curb these effects. Responsibility, kindness or emotional stability help regulate impulsivity. They also favor fair decisions. Without them, coldness becomes recklessness. Furthermore, teams with cooperative climates and clear rules resist these profiles better.

The problem is that, in highly competitive environments, these qualities are often absent. And when a cold leader rises, he tends to surround himself with similar people. This creates cultures that expel those who value cooperation and respect.

Politics should learn from this. A country is not a company, but both share risks. The cult of the leader erodes controls. Transparency gives way to the heroic story. The opposition becomes the enemy. Governing is not always winning, it is taking care of everyone.

It is advisable to qualify. Not all leaders are psychopaths or have traits of that type. Nor are everyone who displays some of these traits harmful. Boldness, for example, can be valuable in emergency situations. However, audacity without empathy becomes recklessness. Therefore, the problem arises when these traits are combined in an unbalanced way.

All of this should make us think: what are we rewarding when we applaud a leader? Their ability to impose themselves or to take care of us? Every time we celebrate coldness, we normalize power passing over people. Maybe it’s time to review our ideal of success. The charisma of evil dazzles, but it usually leaves behind fear, wear and collective damage.

Dolores Fernandez PerezAssistant Professor Doctor. Department of Psychology, University of Castilla-La Mancha

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original.