The search for “something to eat”, often just to eat poorly once a day, is the constant (pre)occupation of Cubans.

SANTA CLARA, Cuba. – For a long time now, the Cuban meat diet has consisted almost strictly of chicken, minced meat and sausages, one of the few “main dishes” that can be found relatively frequently in private sales stands. On the basis of this tiny variety of food – which is usually combined with some rice and, if possible, salad – the thousands of families who have no other source of income other than their precarious state salaries try to survive.

The almost weekly rise of the dollar has had a direct impact on the price in national currency of the scarce Creole proteins and sausages sold by MSMEs and private markets: if a month ago the two-kilogram package of chicken was secretly sold for 1,900 pesos, it is now worth more than 2,000 and it is not so easy to find it after the limit established last year with the Resolution 225from the Ministry of Economy and Planning (MEP).

In one of the stalls of the so-called “Candonga” of Santa Clara, located in the hospital area of the city, and where you can find everything from shoes to frozen products, the clerk practically whispers to two or three reliable customers that she has chicken by the pound. As the owner of the business indicated, he has it hidden in a refrigerator in the back room, as he must have done on many other occasions. when it has been scarce the demanded product. The small bag that he gives to one of the interested buyers costs around 1,500 CUP and contains only eight small thighs. “I have no choice,” consoles the woman who says her husband had gallbladder surgery with dietary restrictions. “I don’t try this chicken, with the substance of the bones I make croquettes for myself,” he lamented.

The search for “something to eat”, often just to eat poorly once a day, is the constant (pre)occupation of Cubans, already subjected to long blackouts, illnesses and deficiencies of all kinds.

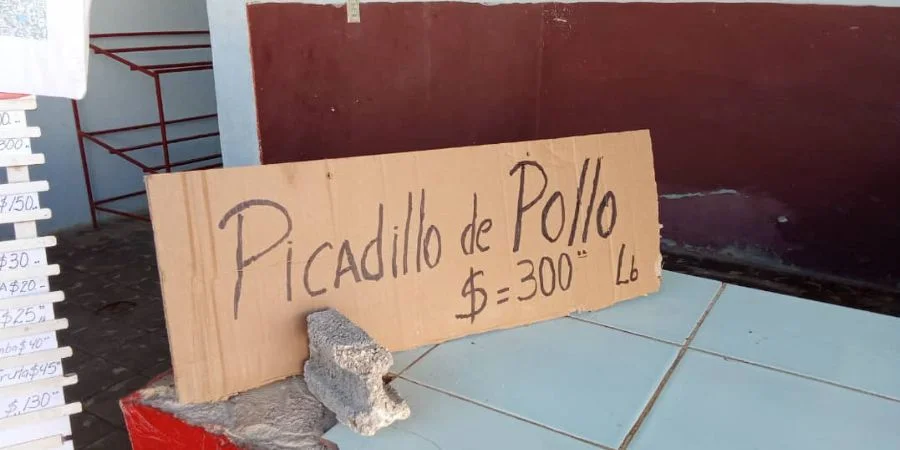

In another similar business on the Highway to Sagua, where MSMEs and food stalls have proliferated in the last year, an old man who looks over 80 years old almost begs the seller to try to weigh him just one pound of minced meat, because what he has on him is not enough for more. It is common for a small fraction of that frozen product, previously cut into rectangular blocks, to strategically exceed one kilogram, although when cooked it barely makes up for a few portions. Even so, the buyer pays more than 400 pesos for the small amount of frozen picadillo and confesses: “With one of these squares in my house we eat twice.”

Mechanically deboned meat (MDM) has become the “star” of Cubans’ daily menu, not because of its flavor or nutritional value, but because it is one of the products that is “most abundant.” Earlier this year, the newspaper Escambray announced with great fanfare the inauguration of a plant in Sancti Spíritus to supposedly process “own MDM with raw materials that are within the territory”, that is, with remaining ingredients from the deboning of pigs, cattle and poultry. The production line, whose cost amounted to about $500,000, promised to diversify the country’s meat supply, but at least in Villa Clara, only individuals sell this type of imported mince.

A self-employed worker, owner of a sales business in Santa Clara, explains that the boxes of this product—especially those of the American brand Harrison Golden Goodness—are purchased for more than $40 through intermediaries, which, according to his accounts, justifies the constant increase in its price in national currency. “It’s not that I’m defending myself, but we [los cuentapropistas] We are not to blame for the chaos that exists in this country,” he says.

“Even the picadillo is already a luxury, because when you come to see, the salary is not even enough for 10 pounds, mind you,” laments Sonia León, a Santa Clara native who says she survives better than others thanks to a family member providing her with previously cooked leftover rice from a daycare center. “Before, at least one was making do with the little they sold in the booth, but apparently nothing is coming anymore. Every day we are left with fewer options for bad food.”

To make matters worse, in addition to meat products, the price of imported rice has also increased, which already ranges between 270 and 280 pesos per pound. In Villa Clara it has not reached the wineries since a couple of months ago, when only five pounds per person were sold corresponding to the month of June. Traditionally, this has been the basic food of the Cuban diet and a family of four consumes on average more than one kilogram per day, so, if they were distributed in small portions for each diner, it would be equivalent to investing more than 15,000 pesos per month in rice alone.

In fact, a report presented by the NGO Food Monitor Program Last May, after applying a survey, it was found that 42% of households should allocate their entire income only to the purchase of groceries.

Almost every weekend the page on Facebook The municipal government of Santa Clara publishes a series of photos with the alleged intention of demonstrating the large influx of people in the vicinity of the Sandino stadium, the most central point enabled for Sunday agricultural sales. Beyond the two or three profiles in charge of enthusiastically supporting these laudatory publications, dozens of comments at the bottom express the impossibility of any Cuban to acquire even two or three of the products that farmers, middlemen and self-employed people sell.

Two weeks ago, the topic of conversation at the “fair” was the high prices of rice: “I spent more than 4,000 pesos and I didn’t bring anything. I had to carry three bags of money,” wrote a user identified as Danelsy Pacheco under the aforementioned images. Another woman, Isabel Gómez, questioned them: “Do not call exploitation a Fair, a Fair is something that is done so that people have relief and in Cuba, like everything else, it is a true ordeal.”