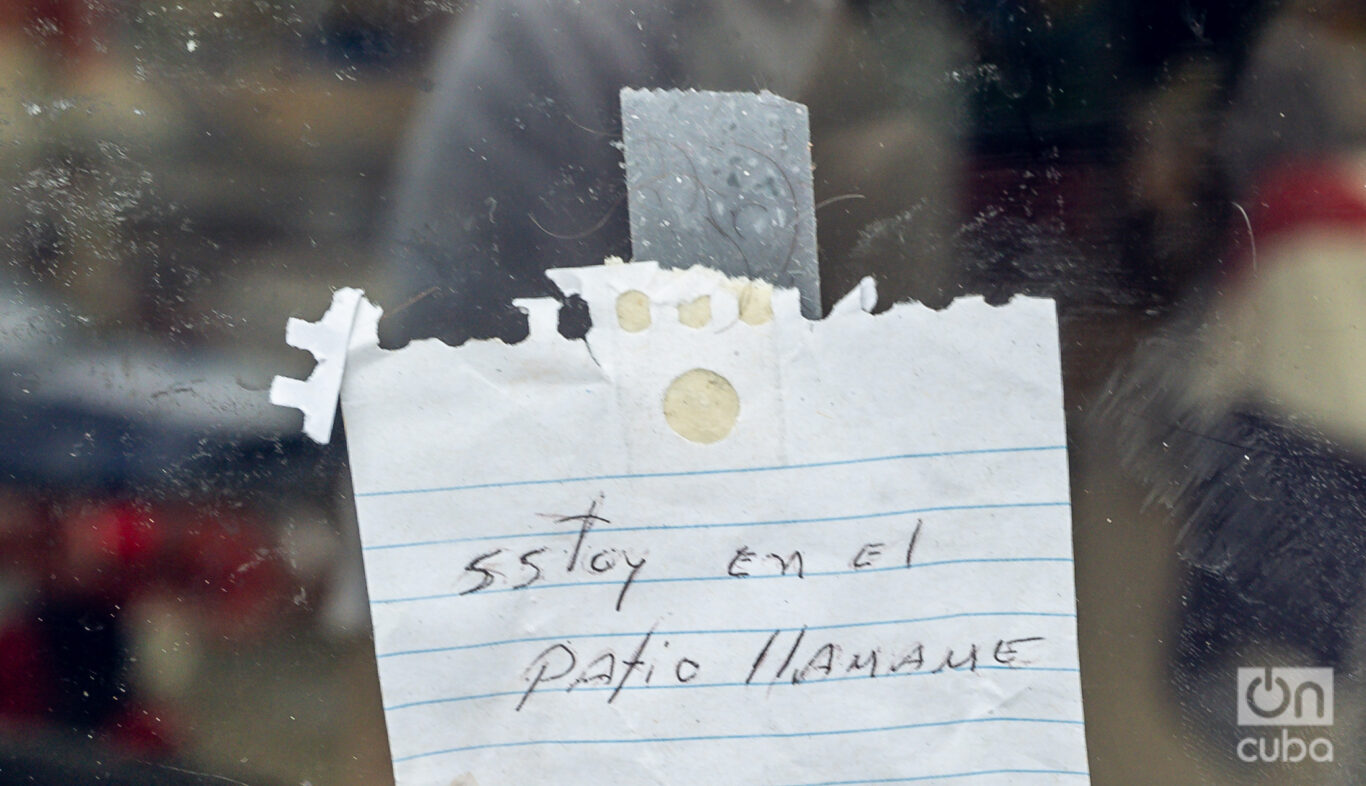

When I arrived in Hialeah, I had the feeling that I had not left Cuba. The same Spanish in the island’s neighborhoods is heard in the streets. There are no English translations in store posters; Nor in the travel agencies that announce parcels and passages to Havana with neon lyrics, or in the clothing stores, or in the typical product stores, where the music of the Van Van or Willy Chirino sounds at full volume.

Hialeah must be one of the very few places in the United States where English is not necessary to speak. Unlike other areas of Miami, where they first receive you in English and then, recognizing your accent, they change to Spanish, here the entrance language is directly ours. English appears just in some lost expression, almost like a compass that reminds that we are north.

It happened to me in the famous Palace of the Juices, where the posters offer mamey, mango and guava, cassava with mojo, malanga and chicharrones fried firms, as if it were a agromercado in Centro Habana. Or in the famous store “ñoooo how cheap”, known as the “Cuban Walmart”, because there you find everything for the Cuban family on the other side of the puddle. There is no trace of American sobriety: everything is color, noise, excess, that way of being in the world that Cubans drag even when we cross borders.

For my ear, “Hialeah” was a known name before stepping on it. As a child, in Cuba, I listened to neighbors, friends or family returning from visiting from the United States. Many said living there. It was like a word that brought news from that other side of the sea, full of migration dreams.

It is no accident. According to the last census, 96.3 % of its inhabitants identify as Hispanics or Latinos and more than 75 % are of Cuban origin. That is why some American media baptized her as “the least diverse city in the country.” The phrase seems contradictory, because what is breathed here is precisely Latin American cultural diversity, but it is true that the Cuban predominates to erase almost any other footprint.

Founded in 1925, Hialeah was born with just 1500 inhabitants and a name of indigenous origin that means “great meadow.” That image of open and green lands contrasts with the current city, turned into an industrial and worker nucleus with more than 230 thousand inhabitants.

History reserved Hialeah moments of unique relief: from the game of the aviator Amelia Earhart In 1937, in his attempt to go around the world, until the filming of scenes of The godfather II in his racecourse in 1974. even his flamenco – symbol of the city – arrived from Cuba in 1934 and ended up becoming an official emblem.

But what really transformed to Hialeah was the Cuban migratory wave. From the 60s, after the triumph of the revolution, thousands of my compatriots settled in this corner of Florida. Then, in the 80s, those who arrived with the exodus of Mariel were added, and in the 90s, those of the “Balser Crisis.” Many chose Hialeah because they already had family or friends in the area, and because here they could speak, work and survive without giving up their culture or learn English.

That is why the city adopted the motto of “the city that progresses.” And yes, he progressed, but he did it in his own way: on the basis of the labor effort, of textile factories controlled by Latinos, of clothing and mechanical workshops where the Cuban and Central American labor holds the local economy. Hialeah is, in essence, a working city.

It is tempting to describe it as a “little Cuba” in exile. But the city is more than that: it is a laboratory of identities, a space where it is negotiated every day what it means to be Cuban, Latin and American at the same time.

Some see a limitation in that cultural homogeneity; Others, a strength. It is paradoxical: on the one hand, it represents the continuity of Cuba outside it; On the other, proof that migration is also a way of founding cities, of resignifying spaces beyond borders.