Ilmarinen, Lemminkainen,

Vainamoinen, Joukahainen.

Where do those words come from? Are they a spell? Are they part of the language of Tolkien’s elves?

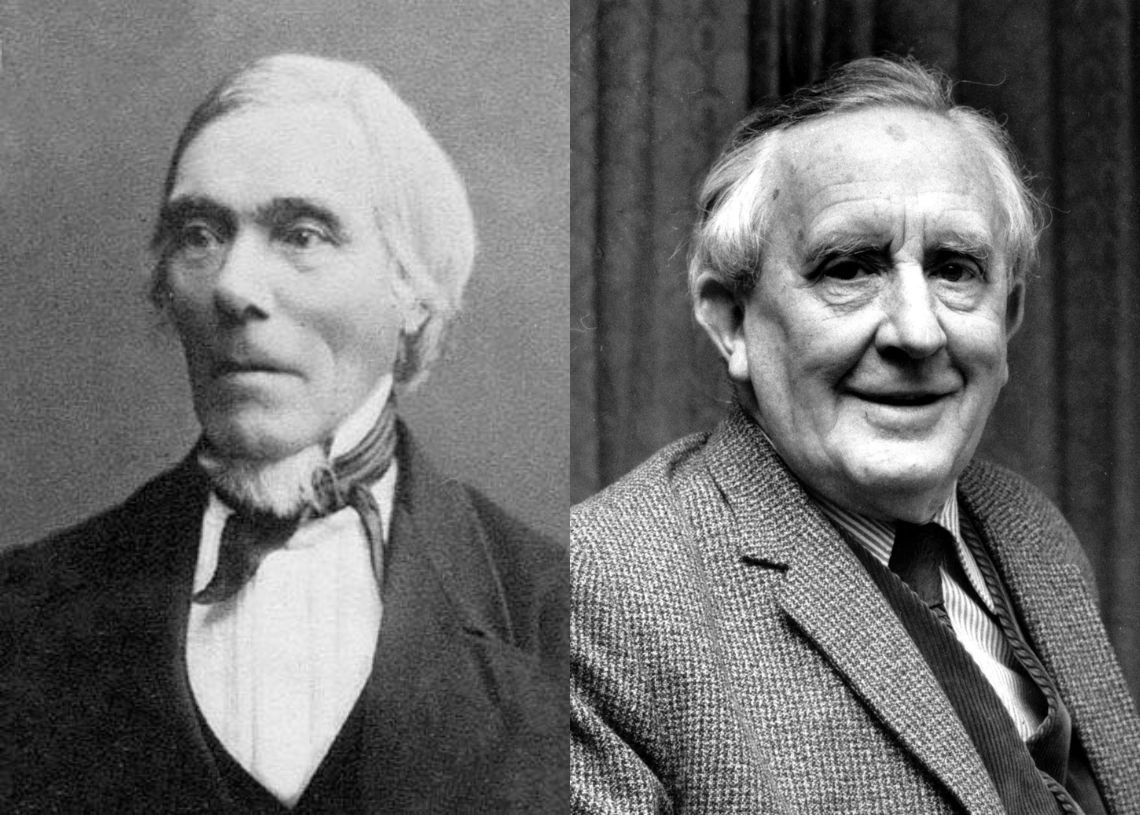

These assumptions are not completely scammed. Although in reality it is the names of four characters from the Kalevalathe epic in verse that in the nineteenth century wrote Elias Lönnrot from the vast and delicate heritage of Finnish oral mythology. Ilmarinen is a fabulous blacksmith. Lemminkainen, a legendary lover. Vainamoinen, an imperturbable old man and is also the Supreme Bard. Joukahainen, an impetuous young man.

Eight accents has the fine verse, so each of those names of four syllables occupies one of the two hemistichs that form it. If we pronounce the four names, one after another, several times, we can get an idea of the cantilena with which the Kalevala enhances the listener or reader in their original language. And it is that the song – in the Finnant song is Runoas well as Runoya He is a singer – constitutes no less than the magic vehicle in the Kalevala universe.

In a previous article we talked about The fascination and poetic use of names. In a way somewhat different from how it happens in the world, the suggestion of the name is where the aspect and interiority of a literary character sprout. “Give me a name, and I will get a story; but not vice versa,” Jrr Tolkien would write successfully. So their names are the master strands of the tapestry of the story, the novel, or the epic.

Beyond the enormous influence they had on the author of the Silmarilion The Finnish language in general and Kalevala in particular, the parallelism between Tolkien and Lönnrot, its predecessor, becomes natural. Both were university professors sui generisand both dedicated their lives to a very similar passion.

Lönnrot, from the Finnish language and literature chair founded in 1850, was the first to dictate courses in Finses in the academic field, breaking with a tradition of five hundred years established by the Swede as the language of culture.

Outside didactic and religious publications, Finnish literature before Kalevala was practically nil. Simultaneously, there was an extraordinary wealth in the oral tradition: the scattered repertoire of popular songs that had been passing from one bard to another, and that were, therefore, always in danger of deforming or disappearing.

This material was the one that Lönnrot dedicated himself to collecting, from his most authentic sources, giving in the process a body and a volume of which those mythological fragments lacked. The day this great work was announced is celebrated as the country date in Finland; With her, Elias Lönnrot put her land and her language on the map of universal literature.

A century later, Tolkien and his philological enthusiasm made a lot to vitalize the study of Anglo -Saxon (also called “Middle English”) and medieval English literature, which, with the exception of Chaucer, was always in the shadows if we compare it with the posterior literary canon that Shakespeare has in her pinnacle.

Tolkien departed, if you want, from a situation opposed to that of Lönnrot: the English language had undoubted literary treasures, but they were not the guy he was looking for. In England there was nothing similar to the spring of stories linked to a specific language, which can be found, for example, in the Greek, Celtic, Scandinavian, Russian, Germanic, or Finnish traditions. Consequently, Tolkien’s work did not include any collection process; had only to create, “with masterful insolence,” he would say Eliseo Diegoan entire universe to be able to find the air, the tone, the fair flavor of their stories.

To these two great, honor and peace.

As a sample button, I submit to your judgment the initial fragment of the Kalevalain a translation prepared for the Infinita Island collection, the editorial seal of the Vitier García Marruz house. Not being able to reproduce in Spanish the alliterations that determine the metric of the original, I have chosen to use white endecasyllables, a meter that flows naturally in our language, and makes an extensive reading more pleasant, although it cannot imitate the envelope rhythmic effect of the original.

A wish has appeared in my soul,

a thought comes to mind.

I will start reciting a song,

To declare it in sacred terms.

I will sing family stories,

the ancient stories of the race;

His words melt in my mouth,

one by one descend slowly,

They arrive in swirl to my tongue,

They crash into a stroke against my teeth.

You, my brother, the beloved,

The partner of my youth,

Come, approach with me to sing,

since we have gathered here,

Arriving from such distant places;

We have rarely encountered,

We can very rarely get together,

In these poor fields of Pohjola,

in the desolate lands of the north.

Then take us from the hands,

We sing the best songs,

Let’s tell the most beautiful stories,

For those who want to listen to them,

and that the young men who grow,

The young people of this happy country,

They can hear if they wish

those ancestral cantilenas,

extracted from the old belt,

The righteous, the impassive vanamoinen,

of the workshop of the blacksmith Ilmarinen,

of Kaukomieli’s fast sword,

from the arrow of young Joukahainen,

With the Pohjola fields in the distance,

and Kalevala’s deep forests.

It was my father who taught me,

while carving the handle of his ax;

And my mother also sang them,

while spun sitting on his wheel;

being a child still attached to the ground,

With the chin dripping milk and cream,

On his knees I liked to screw me.

The sampo was not missing words,

I did not walk Louhi meager in spells,

Among words sampo aged,

Louhi grayed among his fester;

Among his songs he fued Vipunen,

And Lemminkainen died in saying.

But there are still other words,

saturated words of mystery,

found on the edge of the road,

collection of wild grass,

found in rugged thickets,

harvested in the trillos of the forest,

discovered among the grasslands,

When I was just a young zagal,

and carried the flocks to graze

Between mountains of golden flanks,

Every day, among the prados sweets.

The cold has revealed its songs,

And the rain has brought me his runners,

For me, the winds murmured,

And much more brought me the waves,

The birds showed me their sounds

and its verses the treetops.

I made them roll like a ball,

Like a little eye, I roll them up,

And I put all that in my sled,

In my car I placed the skein;

Even the sled,

The car led him to the barn,

And I kept everything in a vase,

I put it in a copper container.

My songs endured the cold,

A long time in the dark they stayed.

Would you have to get them out of that cold?

Can I rescue them from ice?

Should I bring my vessel home

To put it on the stool,

Under the roof carved beams?

Will I uncover the word box,

Open my songs of songs,

cut the knot of the dense skein,

Undil the ball completely?

I would sing the most beautiful songs,

I would report magnificent stories,

If you give me rye bread

And if you give me beer;

But if you don’t give me beer,

And my throat will be dried to the point,

I would temper my voice with water

To cheer up with her this evening

that such a splendid crown,

To announce that the morning arrives,

To greet the return of Alba.