TO

a few kilometers from the Border of Spain with France, my Uncle Grandfather Alberto Jardí rescued a republican flag with the legend: THE INTERNATIONAL TANQUISTS HIS SPANISH COMPANIES

and that in the center has a tank that stands out from a red star.

He kept her in her backpack and, along with her brother Joaquín, concluded the journey that will lead them to exile. They were the first days of 1939.

As both were command cadres of the Republican Army, they were taken to the Algiers-Sur-Mer concentration camp.

I had touched them, things about life, making war on the Ebro River, where the intensity of violence was one of the highest and it is likely that they had already seen everything, but they were missing Algiers.

To say that this was a fright is little. As the French authorities were exceeded by the arrival of thousands of exiles, they made the decision to install them on the north beach of the town, without further protection than the clothes they carried.

In full weathering they had to spend the first weeks, surrounded by barbed wires and the immense Mediterranean Sea.

Many of the boarding schools died from the most diverse diseases and many others because of the abuse they suffered from the guardians of the place, some of them Senegalese.

The Republicans were organized as they could and that made the construction of Barracas and the most elementary health services possible.

Poet Agustí Bartra wrote a powerful and shocking story about it, Christ of 200,000 arms.

The grandparents were lucky, yes, to be able to occupy some of the few places that remained in the ships that transferred the Spaniards to Latin America. They spent a season in Cuba and another in the Dominican Republic, from where they moved to Mexico.

For them, the contrast was always evident. In France they were locked on a beach, and in Mexican territory they were received with music, they were taught to take Tequila and gave them the quality of refugees, which otherwise required the activities they had carried out in the Civil War.

The stirred ones, as José Gaos called them, promised with their host land and founded institutions such as the College of Mexico and not a few stood out in chairs in the UNAM, but the vast majority were workers, employees, artisans and peasants who had opted for support a political project subject to democracy, to law and freedom.

Therefore, among other reasons, they were always grateful to General Lázaro Cárdenas and Manuel Ávila Camacho, who as presidents of the Republic made it possible to find, far from their land, another homeland.

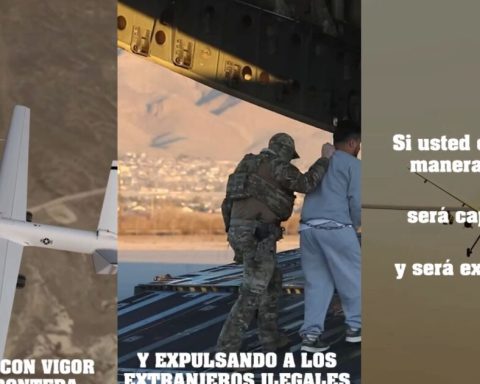

I remember with these lines only a small story, perhaps private, but that has an extension with what happens today, where migrants are expelled from the United States.

Yes, 1939 was unleashed as a result of a war, but what now happens is also, although with other rules and pretexts that, deep down, have the purpose of dismantling the entire international system for protection for migrants.

That this also happened years ago and if we measured it for decades, because the anxiety has always been present in the Mexican and Latin community, but it has the novel component of which it is part of one of the propaganda strategies of President Donald Trump.

Hence it is understandable that the Government of Mexico receives the countrymen in its obligatory return, but that it does the same with those of other nationalities, who often abandoned their country in displacements forced by economic conditions or violence.

The crisis that is already drawn on a horizon, caused by Trump, must have an answer, placing, precisely on the court of the rights and defense of people.

If the United States closes to the world, Mexico has to maintain another vision, faithful to that of its traditions.

*Journalist