HAVANA, Cuba. – To the Spanish president, Pedro Sanchezhas decided to dedicate the first days of 2025 to celebrating the 50th anniversary of the death, in November 1975, of the dictator Francisco Franco. It would be better if, instead of dedicating himself to perpetuating the memory of the tyrant, he had waited until 2026 to celebrate the half-century of the transition to democracy. But Pedro Sánchez, with the authoritarian desire that he has demonstrated in his attempts to circumvent the laws and tie up the press and the judiciary, is not very interested in democracy. Perhaps, deep down, he even feels envious of the power that Franco had and that is why he cannot stop evoking it.

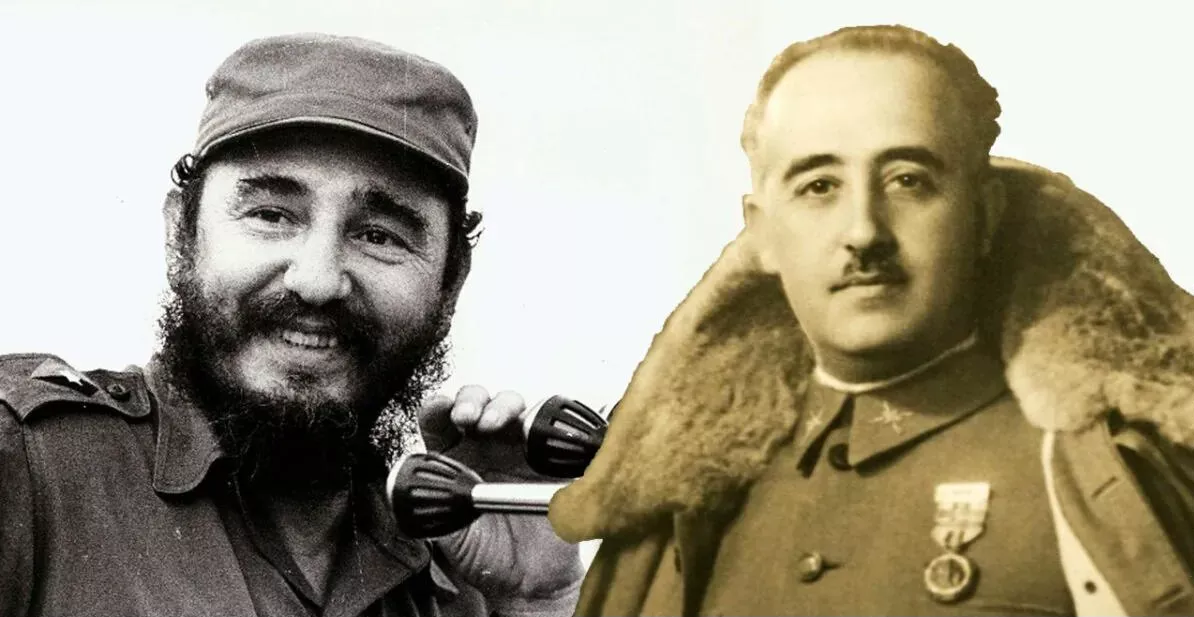

As there were many similarities between the regimes of Franco, the “Caudillo del Ferrol”, and Fidel Castro, the “Commander of Birán”, now I have to think about what it would be like if in 2066, when in one way or another it must have ended Castroism and its sequel, late Castroism, it occurs to those who are then ruling in Cuba to dedicate the year to commemorate the half century since the death of Fidel Castro.

Return, as the official media does today, to the monotonous recounting of his guerrilla events, his very long speeches and delirious plans? So that? To relive the decades of nightmare that the Castro regime and its successors meant? It would be, as the letter of Wither shade of palethat old Procol Harum song, “keep alive fandango.”

Yes, still, in the midst of the hardships in which they live today, there are old people nostalgic for Fidelism who never tire of repeating that “with Fidel these things did not happen.” They never accept that today’s mud comes from the Fidelista past. They are convinced that “the errors, the bad things, were because Fidel did not know, that if he had found out…”.

Some of that nostalgia may be inherited by the descendants of those who took advantage of the crumbs of Castroism, and that even the compatriots who, after the State-Party-Government always thought and decided for them, miss the communist past, They feel unable to responsibly manage their freedom. I can already imagine those who will complain that “they didn’t have to work so much before,” just as some emigrants lament today that “in La Yuma there is everything, but you have to work too much.”

Dictators are better forgotten. And the sooner, the better. But those of us who have lived in dictatorships know that it is not easy.

Why deny it? Whether we wanted it or not, all of us who lived under Fidel Castro’s regime were in his film, even as extras, poorly paid or free, to the gun. It was a poor people’s party in which the vast majority of us had to dance with the ugliest while the new class ate the sweets. If we wanted, depending on our mood and ability to pretend and crawl, we could dance, wiggle, sing, hum or follow the rhythm of the little music with our feet or by clapping our hands. At least, until they put us in jail, we left the country or we died of rage, boredom or sadness.

It was not possible to evade Fidel Castro. In Cuba or outside it, we cannot escape its influence. We act as victims or perpetrators, as adversaries or accomplices, as informers and those who are betrayed, as repressors and those who are repressed, as shouters and those who are silenced. We were nails, screws and nuts. And the “Maximum Leader”, owner of the anvil, handled the hammer, screwdriver and pliers as he pleased.

Years will pass after the great funeral and the shadow of Fidel Castro will follow us. Maybe many of us can’t get rid of it. We may never achieve a normal existence. Bad memories will haunt us. Most likely, we will not be able to forget. Will it be of any use to impose the remembrance of Fidel Castro on our descendants as well?