Human rights specialist and member of the advisory board of the Venezuelan Human Rights Action Education Program (Provea), Marino Alvarado, explains that forced disappearance is often used as a strategy to instill fear in citizens. The feeling of insecurity that this practice generates is not limited to the relatives of the missing person, but affects their community, the work team and society as a whole.

Author: Venezuela Time

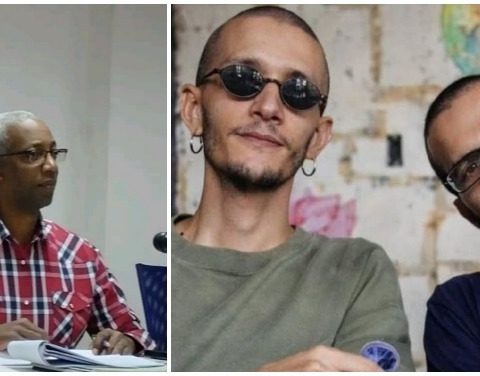

Since January 7, Carlos Correa’s relatives, co-workers, colleagues, activists and students did not know his whereabouts. That day, the journalist, human rights defender and director of the non-governmental organization Espacio Público was intercepted in the center of Caracas and detained by alleged security officials, who were wearing dark clothing and hiding their faces with balaclavas.

The disappearance was reported by his wife, Mabel Calderín, and by members of different NGOs after visiting the headquarters of the Bolivarian Intelligence Service (Sebin) in Plaza Venezuela and El Helicoide – in the Venezuelan capital –, as well as the Military Counterintelligence Directorate. (Dgcim) in Maripérez, to try to know his whereabouts. The answer in all places was the same: “Carlos is not here.”

“The legislation of the world severely punishes forced disappearance because it is not only a crime against personal freedom but also against the exercise of rights,” says Zair Mundaray, former director of procedural action at the Public Ministry.

After 8 days of searching, requests for information and even a writ of Habeas Corpus, which was denied, on Wednesday, January 15, the 52nd prosecutor with National Competence in Economic Crimes, Alirio Mendoza, confirmed to Calderín that Carlos Correa had was presented before the Fourth Control Court with Competence in Terrorism on Thursday, January 9, two days after his disappearance. He did not have access to private defense, as he was assigned a public defender.

In that meeting with Calderín, the prosecutor said that he could not report on the alleged crimes of which Correa was accused. He also did not disclose the place of confinement to family members or defense attorneys. The only thing the official confirmed was that Carlos Correa was in prison, but he refused to offer details.

In the early hours of January 16, Carlos Correa was released from prison with precautionary measures. Despite his conditional release, he was a victim of forced disappearance.

*Read also: ABC of censorship: fear

“Forced disappearance is often used as a strategy to instill fear in citizens.s. The feeling of insecurity that this practice generates is not limited to the relatives of the missing person, but affects their community, the work team and society as a whole. Unfortunately, it has become an increasingly common practice in Venezuela,” explains activist Marino Alvarado, member of the advisory board of the Venezuelan Human Rights Action Education Program (Provea).

Alvarado recalls that, in the past, forced disappearance was a symbol of military dictatorships, but in the Venezuelan case, it has become a method of repression against political opponents, including party leaders, human rights defenders, journalists or relatives of these people. All this supported in a fight against terrorism, as a kind of patent to fail to comply with the norm that designates forced disappearances as a State crime, he considers.

Other human rights activists agree with Alvarado. Through a statement signed by the NGO that Correa directs, Espacio Público, they expressed that his case “is part of an intensification of post-electoral repression that seeks to silence social leaders, human rights defenders and political opponents.”

Crime become the norm

Criminal lawyer Zair Mundaray, former director of procedural action at the Public Ministry (MP), maintains that Venezuela is part of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons against Forced Disappearances of the United Nations (UN). The Penal Code establishes penalties of 12 to 20 years in prison for any authority or person in the service of the State who unlawfully deprives a citizen of his freedom and refuses to acknowledge his whereabouts.

“The United Nations committee has issued warnings about what is happening in Venezuela. “Forced disappearance is so serious that it is among the crimes against humanity of the Rome Statute,” explains the person consulted.

But in detentions for political purposes, state agents have made the practice of forced disappearance the norm, he warns.

“Forced disappearance is often used as a strategy to instill fear in citizens,” explains Marino Alvarado, member of Provea’s advisory board.

“Forced disappearance can be an arbitrary detention, arrest, kidnapping or any form that begins with the deprivation of liberty. Then, there is a denial from the person who has the person that they actually have it. The legislation of the world severely punishes forced disappearance because it is not only a crime against personal freedom but also against the exercise of rights,” he explains.

Victims of forced disappearance are deprived of the guarantees established in the Constitution and the laws, such as the right to appear in court within 48 hours after arrest; to receive legal assistance, find out the reasons for the arrest or communicate with their families.

“People who have a person and deny that they are there have committed the serious crime of [artículo] 180A of the Venezuelan Penal Code which is forced disappearance. But the two organizations called to prevent this from happening, the Ombudsman’s Office and the Public Ministry, are participants in the disappearance. This is very serious. Especially in the case of Tarek William Saab, who supports it after many days of forced disappearance, they put these people to order and he pretends that they have just been arrested through false police reports,” he adds.

In Venezuela, 18,237 political arrests have been registered from 2014 to date, according to figures from Foro Penal. Most of them began as forced disappearances, Mundaray reiterates, because the authorities refuse to identify themselves by name and position and explain the reasons for the detention, as required by current legislation.

“Now they do it [funcionarios] hooded, with long weapons, without banners [del organismo de seguridad]. They all act nocturnally, they dress in black. There begins a situation of forced disappearance because that detention could have been committed by a group, a guerrilla or criminal group or a State security agency,” details the lawyer.

In Venezuela, these cases have a pattern: the security forces do not provide information on their whereabouts, although families tour the detention centers and ask if they are there; The prosecutors present the victims outside the scheduled period and the judges endorse the process with false records, the lawyer denounces.

“There is a whole framework in the system to allow forced disappearance to occur. Even with the creation of clandestine torture centers as has been documented with the Dgcim (General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence), the Sebin (Bolivarian Intelligence Service) or the Directorate of Strategic Actions (Daet) of the Bolivarian National Police,” he comments.

Cases recorded in 2025

The case of Carlos Correa is not the only one that serves to show how forced disappearances become a recurrent and common practice by the Venezuelan State.

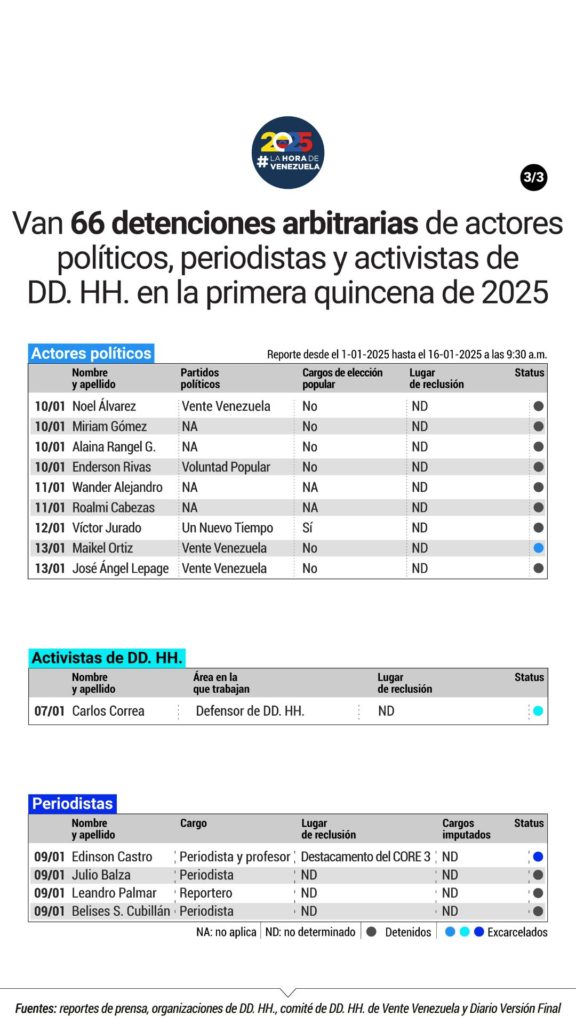

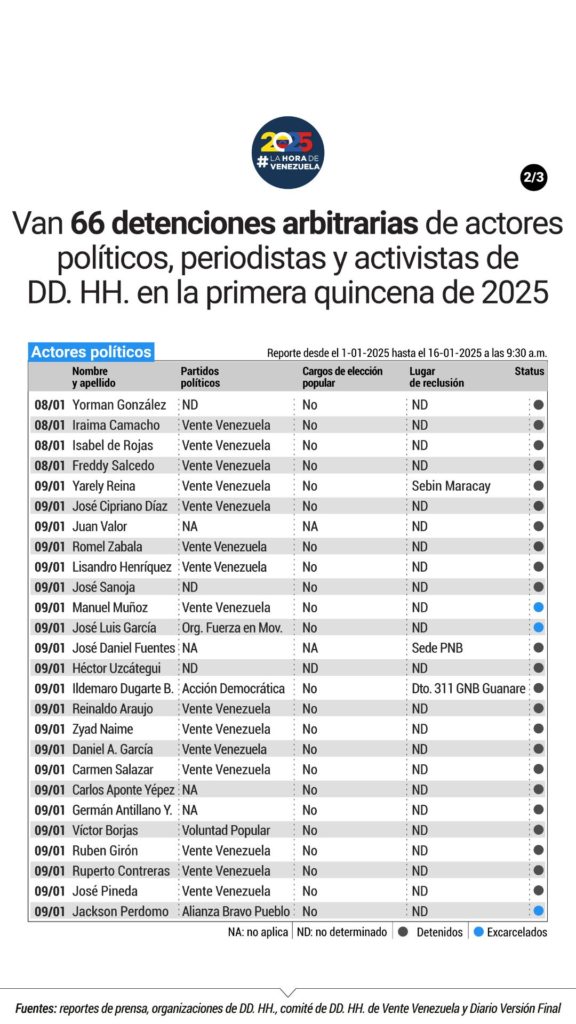

Until January 15, 2025, relatives, organizations and citizens denounce the forced disappearance of:

Enrique Marquez. Former presidential candidate and coordinator of the Centered with the People party was arrested on January 7. “He was kidnapped by vigilante groups that, using force as law, intend to silence and intimidate those of us who want a better country and have a different vision,” said his wife. As of the date of publication, there is no information about his whereabouts and he was linked by the Government to “conspiracy plans.”

Angel Godoy. President of the Democracy and Inclusion Movement and was arrested on the afternoon of January 8 by officials of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service in Los Teques, Miranda state. This was reported by Nicmer Evans, founder of the organization, through his social networks. His sister, wife, children and friends ask for proof of life because his whereabouts are unknown.

Julio Balza. He is a member of the press team of opposition leader María Corina Machado and was arrested after the rally on Thursday, January 9 in Caracas. His defense filed a petition in court because his family has had no information about him for more than 5 days. Unidentified officials intercepted him in the Chacao municipality.

“In Venezuela, 18,237 political arrests have been registered from 2014 to date, according to figures from Foro Penal. Most of them began as forced disappearances,” says Zair Mundaray, former director of procedural action at the Public Ministry.

Noel Alvarez. Former president of Fedecámaras and head of the @ConVzlaComando in the state of Miranda who was arrested on January 10. His daughter reported, on social networks, that she is unaware of his location, conditions of detention and accusations against her father. “Family members cannot and should not be satisfied with assuming that they are presumably in the custody of some State agency,” Saab told prosecutor.

Enderson Rivas. He is a leader of the Voluntad Popular political party in Yaracuy. On January 10, his arrest was reported in Chivacoa, Bruzual municipality. Until now, it is unknown which agency carried out the procedure and the whereabouts of Rivas. The Committee for the Freedom of Political Prisoners in Venezuela (Clippve) also expressed its concern about Rivas’s situation and held the Venezuelan State responsible for guaranteeing his integrity.

Rafael Tudares. He is the son-in-law of Edmundo González Urrutia, who reported his kidnapping on January 7. Tudares was intercepted while taking his children to school. Hooded men dressed in black forced him into a van. Since then, his whereabouts are unknown. “My grandchildren lived a moment of terror when they took their father away. That terror grows every day due to his absence. 7 days later we don’t know where or how Rafael is. “We want justice and freedom!”

There are other names that appear in reports such as those of UN missions and working groups that have documented cases of detentions that began with reports of kidnapping and forced disappearance. These mentions include Anthony Michell Molina Ron, Emirlendris Carolina Benítez Rosales, María Auxiliadora Delgado Tabosky and Juan Carlos Marrufo Capozzi, Josnars Baduel, Oreste Alfredo Schiavo Lavieri, José Javier Tarazona Sánchez, Ramón Centeno Navas, Juan Nahir Zambrano Arias, Olvany Marian Gaspari Bracho, Uaiparú Güerrere López, José Ignacio Moreno Suárez, Luis Enrique Camacaro Meza, Dignora Hernández Castro, Williams Daniel Dávila Barrios, Perkins Asdrúbal Rocha Contreras, Yenny Lucia Barrios Torbello and Biagio Pilieri Gianninoto, registered between 2023 and 2024.

The forced disappearance, as well as the arbitrary detentions, torture and cruel treatment recorded in Venezuela in recent years, are part of the investigation opened by the Prosecutor’s Office of the International Criminal Court for the commission of crimes against humanity carried out by members of the Venezuelan State. or collectives, according to Provea.

*Journalism in Venezuela is carried out in a hostile environment for the press with dozens of legal instruments in place to punish the word, especially the laws “against hate”, “against fascism” and “against the blockade.” This content is being published taking into consideration the threats and limits that have consequently been imposed on the dissemination of information from within the country.

Post Views: 760