SANTA CLARA, Cuba. – Years before his death, Manuel Corona would describe in his diary the situation of poverty that afflicted him and the very few friends who used to visit him while he was admitted to the La Esperanza sanatorium for tuberculosis patients. In those brief lines written in a school notebook, one of the greatest Cuban troubadours meticulously reviewed, from the daily body temperature, the care that his friend gave him. Maria Teresa Verato how he got some pesos by playing the lottery within the hospital itself.

Corona entered the sanatorium in the summer of 1940, ten years before the illness he suffered ended his life on the night of January 9, 1950. “I went to Havana on a pass to take up a collection and buy anaphylaxol injections.” , noted in the aforementioned record in which he also detailed his precarious diet: “I had my mother visit. They brought me oranges (…). My namesake Manuel Cierra brought me a custard apple, a quarter can of bell peppers and 20 cents.”

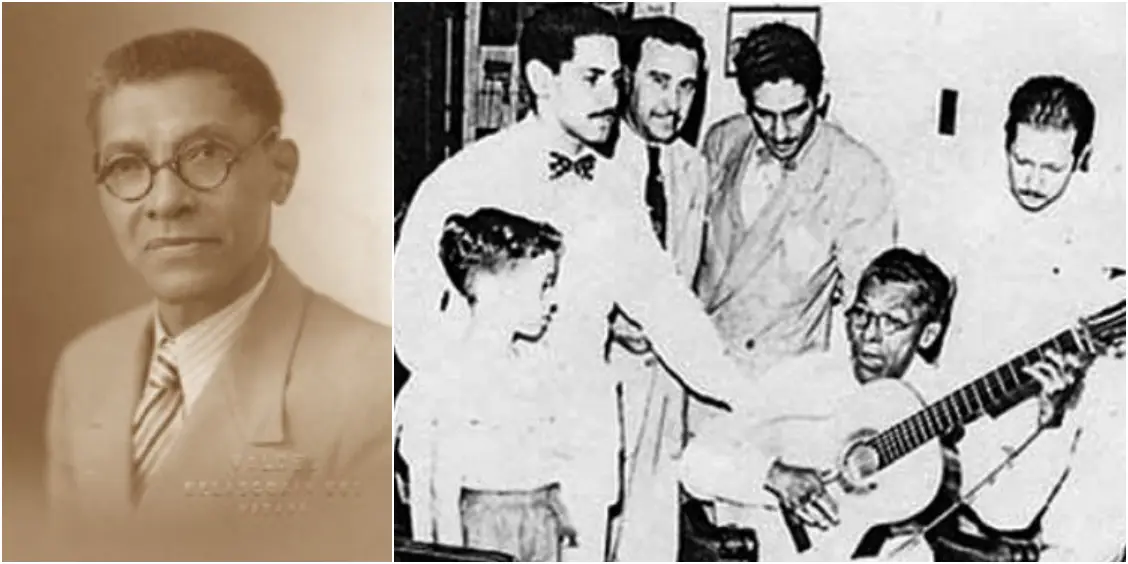

Manuel Corona Raimundo, born in Caibarién, then province of Las Villas, went to try his luck in the capital while still very young to initially earn his living as a shoe shiner, cigar maker and sweeper, until he managed to teach himself to play the guitar. The musicologist Lino Betancourt describes that he mastered the instrument quite precisely and that at that time he looked “neat, elegant, of good appearance”, the antonym of his last years of life.

During that prolific period, Corona created a hundred compositions, among which are Saint Cecilia, mercedes, The Alfonsa, Adriana and Longinaand many others with female names, so he would go down in immortality as the Cuban bard who would write the most songs for women. “He was a regular guest to entertain gatherings in the homes of wealthy people, but he never abandoned his friends, the troubadours with limited resources,” Betancourt continues. It is said that, in addition to the glories, he never wanted to leave his rented room in the poor neighborhood of San Isidro, where he even got to know Alberto Yarini.

Although Corona was well known in the Havana bohemian scene and aroused the admiration of great figures who stood out on the troubadour scene, the economic situation of many of these musicians was truly precarious. In a letter sent by María Teresa Vera while she was admitted to the sanatorium, it reads: “I’m glad you’re better… I didn’t send you the grapes because I don’t have a cent.” A good part of the composers based in Havana used to meet in the room of the La Maravilla solar, where Vera lived, who premiered most of the great songs of this troubadour whom he considered “his brother.”

Right in this room on San Lázaro Street, Corona commissioned the theme Longina. The muse had attended one of those gatherings accompanied by Commander Armando André, who deposited some coins in the hands of the hostess to guarantee the “sopón” of the agreed day on which they would premiere the song. “What a rascal you were! “We already have Sunday lunch assured!” Those present said to Corona as a joke, testimony compiled in Betancourt’s text. What my song says.

Although there has been speculation about Corona’s multiple loves, in reality he had only one wife named Eulogia Real, known as Yoya and with whom he had two daughters who died at an early age. The oldest took her life at 17 and the youngest would die at five from acidosis, two losses that would plunge him even deeper into the alcoholism that he suffered until his death.

After being discharged from the sanatorium, Corona had to wander through seedy bars and cheap inns “in search of a few cents to support himself and to be able to take the little he could get to his elderly mother,” says Betancourt himself. The cabarets and lounges on the beaches of Marianao were his center of operations in the last months of his life, where he performed all those songs that brought him glory until early morning. He walked around in threadbare, dirty, and faded clothes, with his old guitar as his only companion.

On the cold night of January 9, 1950, he implored the owners of the Jaruquito bar to let him sleep in the little room where they kept the empty bottles. The next day they found his emaciated body twisted by the cold, wrapped in newspapers and hugging his instrument. Local residents initially mistook him for a drunken homeless man or a criminal trying to escape justice.

In an article about the event, the writer María del Carmen Mestas reports that the owner of the bar rebuked the reckless witnesses: “They don’t know what they are saying. This man is Corona, Manuel Corona, one of Cuba’s greatest composers. He lived in the greatest misery; Therefore, I allowed him to sleep here. “What else could I do.”

Thanks to a collection made by bus drivers on route 32 in the capital, his wake was held at the San José funeral home, which was later moved to the headquarters of the Society of Troubadours. At the mourning farewell called at the La Lisa cemetery, where he was originally buried, Gonzalo Roig exclaimed: “Troubadours take out their guitars, the best of them all has died.”