HAVANA, Cuba. – I remember that there were few New Year’s Eve parties in 1991 in which it was not heard, along with Bilirubin and the I hope it rains coffee by Juan Luis Guerra and the revamped boleros of Luis Miguel, the It’s coming of Willy Chirino.

Many of us expected that 1991 would be the last year of the Castro regime. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, the communist governments of Eastern Europe had collapsed with astonishing speed. On December 25, 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev resigned from the presidency of the Soviet Union, a country that had been dissolving and that six days later, on December 31, would officially cease to exist, becoming the Russian Federation.

The Castro regime had been left orphaned, without a ladder and hanging by the brush. Everything indicated that change was inevitable and that, one way or another, democracy would come to Cuba. But it didn’t happen like that.

In reality, we needn’t have gotten our hopes up. A statement from the Political Bureau of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) had warned that the single party, the state-planned economy and the leadership of Fidel Castro were not among the issues to be debated in the assemblies prior to the IV Congress of the PCC. Woe to anyone who dared to speak out in meetings for something that smacked of multi-party system and market economy!

In the IV Congress, held in October 1991 in Santiago de Cuba, immobility was imposed. The only changes that occurred were the approval of some self-employment, the direct elections of deputies to the National Assembly of People’s Power and that the Communist Party, which declared itself in charge of “saving the country, the revolution and socialism ”, added the label “Martian” to that of Marxist-Leninist.

Fidel Castro stubbornly proclaimed “socialism or death.” And we almost literally died of hunger, because, when the Soviet subsidy ended, everything became scarce and the nightmare ensued that the bosses, always given to euphemisms so as not to call things by their names, baptized the “special period in peacetime”.

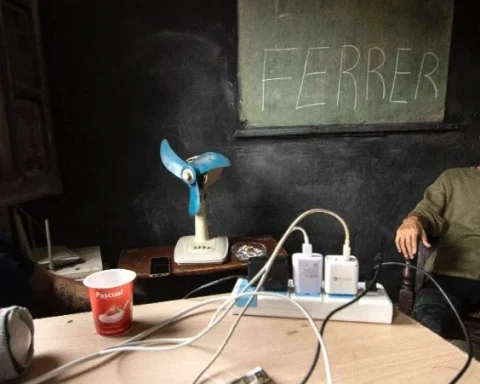

Corroborating that under Castroism everything can always be worse, that nightmare of Special Period It seems insignificant, pale to us, with the much more gloomy situation of today, with hunger and blackouts multiplied several times, to which the bosses of post-Fidelista continuity have dragged us with their failed and disastrous economic policies.

And again at this end of the year, the worst and saddest of the last 66 years – when, for lack of reasons to celebrate in few Cuban homes there will be a party -, the premonition prevails again, as in that December of 1991, that This year will be the last of the dictatorship.

Many, disappointed, claim that they have been hearing this for a long time and it has not just happened. They are right, but it seems that now it will be.

Even the most skeptical and hopeless believe that “something big has to happen.” And it will not exactly be a miracle, Russian or Chinese, that saves late Castroism.

The regime is facing the most adverse of the situations it has had to face. Despite the triumphalist tone, his desperation is evident. All its possibilities have been exhausted. There is more and more discontent and despite threats of more repression against those who protest, it seems inevitable that a popular outbreak of incalculable magnitude will occur. And to make matters worse, in the midst of an unfavorable international scenario, in a few weeks, the Trump administration will be upon us, with the Cuban-American Marco Rubio as Secretary of State, which will probably tighten the sanctions.

The pitcher has gone so far to the fountain that it is time for it to break. It is not known what it will be like, but if it breaks, it breaks. The life of the Cuban nation is at stake.