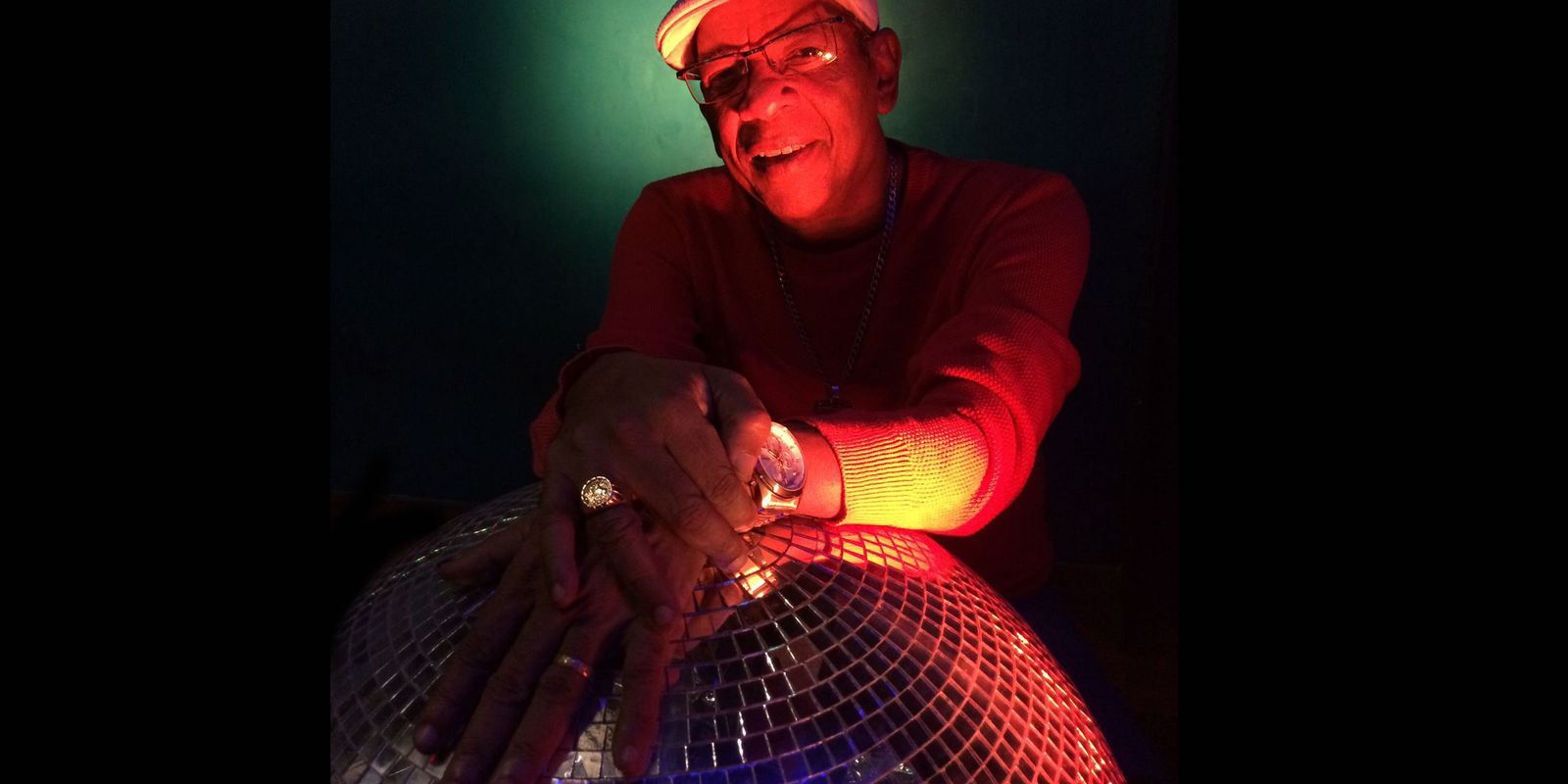

“THE black music it is a force, it is a collective dialogue”, describes cultural producer and civil engineer Asfilófio de Oliveira Filho, better known as Dom Filó. This Friday (8), he will lead, alongside Marco Aurélio Ferreira, DJ Corello, the first edition of the Eu amo Black Music dance, in celebration of 50 years of Black Music in Brazil. The party is held by Teatro Rival Petrobras, in the center of Rio de Janeiro, and by Cultne TV.

In 2024, the celebrated milestone is the creation of the Noite do Shaft ball, in 1974, at Renascença Clube, by Dom Filó, which marks the arrival of black music in the country. The party is named after the character John Shaft, played by Richard Roundtree in a series of films released in the 1970s.

“He is a detective who conveyed a very positive image of the black community. This series was remarkable because we didn’t have the presence of black people on television at that time. It was an all-white program, and then we have a black hero”, remembers Dom Filó. “We took the African-American essence and gave it a new meaning here in Brazil.”

Black Music in Brazil

According to the music producer, the black music (“black music”, in Portuguese), originated in the cotton plantation fields of the United States, where enslaved black people used singing to soothe the pain of slavery. This sound gave rise to different musical rhythms, soul being one of them. “Soul means soul. Soul music is the music of the soul”, comments Dom Filó. “This essence is born in the cotton fields of the United States, but when it passes into entertainment, black American music is born, soul, rhythm and blues, jazz and blues are born.”

“Black culture has always been musical”, says Dom Filó. “Since the times of slavery, our great leisure activity was to get together to ease the pain a little. Those meetings, the drums, the songs and the dances came through time.” With a father from Minas Gerais and a mother from Rio de Janeiro, Dom Filó says that he has always been involved with musical culture, especially from samba schools and African-based religions. Around the age of 18, he started attending the Renascença Clube, founded by a group of young black people. “ “Renascença gave us access to cinema, theater and, mainly, music. There, we listened to a lot of things on the radio, which was the great top of the time.”

It was through the radio that different foreign musical expressions reached Brazilian ears. Among them, black music, with a large presence at dances in Rio de Janeiro.

“Braiding a timeline, you will have several 50 years. Brazil already consumed black musicbut without promoting it, without accessing it as black music”, he observes.

“You had record stores, importers, but few had access to those records. Later, DJs were able to reach these shelves, bring in records from outside and form their clubs through the sound teams. But, before the sound teams start their parties, we have another characteristic of this music’s penetration, with national artists who received direct influence from soul music and they even went to live on American soil, like Tim Maia and Tony Tornado”.

“At that time, there was no talk of black music or in black music, but in MPB with a different accent, the black accent”, says Dom Filó. With the development of sound teams, there is a need to create parties to bring people together in search of the same sound. “That catharsis, of bringing the whole crowd into one room and playing that pulsating, emotional music; pure dance, pure self-esteem. This is the essence of the dance”, he comments. One of these parties was Soul Grand Prix — also a musical group formed by musicians from Renascença Clube, such as Dom Filó — which was born not only for fun, but also to discuss racial issues.

“We suffered a lot, we lived in pain all week. It was discrimination all the time, low self-esteem. When a team like Soul Grand Prix comes, which passes on to the community the need for self-esteem, belonging and identity, people change their behavior, their appearance. Even though we lived through that moment of dictatorship, when we, black people, were massacred, we still managed to spend a little time black power (black power).”

Black Rio Movement

The dissemination of black music in Brazil through radio stations was not limited to dances promoted for the black community, but gave rise to a musical and cultural movement concentrated mainly in Rio de Janeiro, recognized as the Black Rio Movement. American black music to the city’s suburbs, giving rise to a generation inspired by the demand for their rights, which adapts the North American style to the national reality. The mix of soul and funk with samba gave rise to the band black rio, modernizing the Brazilian sound.

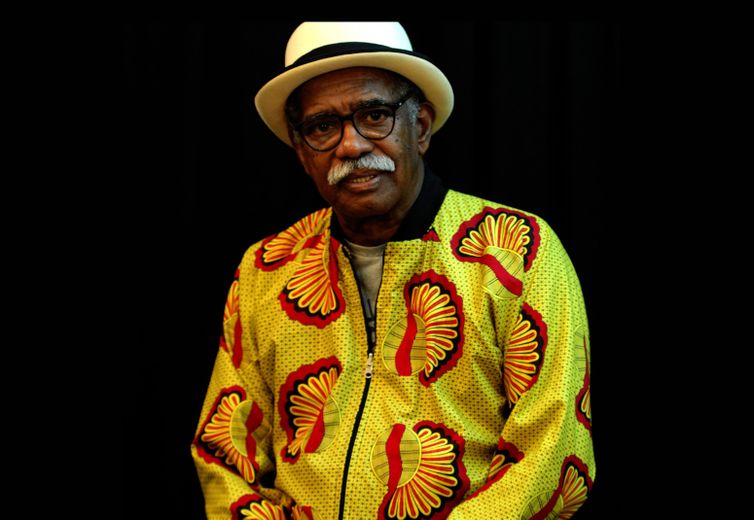

Author of the book 1976: Black Rio Movement alongside journalist Zé Octávio Sebadelhe, Luiz Felipe de Lima Peixoto describes that the Black Rio Movement was not a planned action, but “something totally organic”, arising from the need for the black community to express itself through American music. “It was a form of affirmation of black identity in a heavy period of military dictatorship in our country.”

According to Peixoto, the origin of the movement appears long before the introduction of black music in the country, when the radio started to promote samba to the general public, in the 1940s and 1950s. Its popularization attracted the middle class, made up mainly of white people, to samba schools, which were no longer “ searched” by the police. “Until that moment, samba was something for outsiders, for scoundrels. Black people who no longer identified with all of this ended up identifying with black American music and all its historical claims from that period.”

The expert considers that the Black Rio Movement was fundamental for the creation of black resistance in a period of oppression, as well as for the affirmation of black identity in Brazil. “At the dances, especially those promoted by Dom Filó, anti-racist speeches and affirmations of blackness were given during the songs. This entire storyline, the parties, the music, the clothing, contributed to this reaffirmation of a more positive black identity.”

At the turn of the 1970s, cultural expression began to lose strength. The popularization of nightclubs was one of the reasons that contributed to this new scenario.

“The change in the public’s musical preferences and cultural evolution, but, mainly, the persecution, repression, censorship and surveillance that was more evident at dances at the time, were crucial points for the decline”, highlights the author.

Even with the decrease in the strength of this demonstration, Dom Filó highlights the relevance of the Black Rio Movement in the country, which began to be seen from a black perspective. “This movement was very important in terms of behavior, belonging, identity and self-esteem, all of this using ancestral technology that has been worked on to this day so that our community, the black community, can be repaired. We only use music as an element.”

Charm Movement

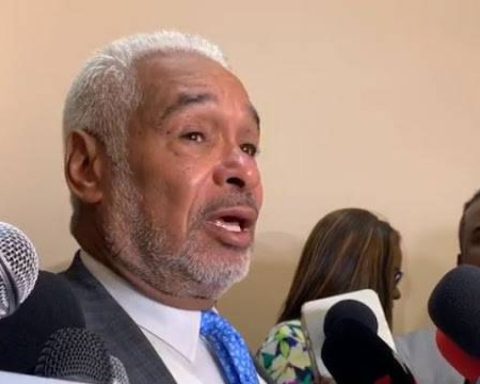

One of the most striking expressions of this period of musical transformation in Brazil is Movimento Charme, created by DJ Corello (featured photo). THE Brazil Agencyhe says that the movement began when he himself took the initiative to play a musical genre other than soul at dances. black musiclike the rhythm and bluesshortened to R&B. “I was the first DJ in soul leaving the soul and enter another path. In the soul days, you had to dance to one song and stop to get into the rhythm of another, but I was already thinking about the mix”, he recalls.

“Movimento Charme, which began in the 1980s, began with this feel of one song within another. This sound caught another generation, which was not the soul generation, with virgin ears. I managed to catechize this generation for the Charme Movement”, he continues. DJ Corello is also credited with using the term “charme” to identify the movement, which he always said at dances

“It’s time for the charminho, have sex with your body very slowly” to announce the change in the musical repertoire.

For many years, the movement had the Viaduto de Madureira as the main reference of charm in Rio de Janeiro, but, with the change in repertoire, which began to play other musical genres in addition to R&B, Baile Black Bom, created in 2013 at Pedra do Sal, in the Saúde neighborhood, took on this role. Despite no longer representing charm in the same way as in the past, the DJ highlights that the Madureira Viaduct should not be forgotten, because it was important for the cultural manifestation. “Today, Black Bom is a reference, in five years, it will be another, because it is a constant evolution”.

Black music in Brazil

“When I think about music in Brazil, I think that all music acquired in the country has dark marks”, says Denise Barata, professor at the Department of Education at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (Uerj).

She argues that music in the country is built on a black experience, resulting from the African diaspora that caused the displacement of more than 12.5 million Africans to the Americas and Europe between the 16th and 19th centuries, as discussed in article “Music in the African Diaspora of Latin America”. Thus, musical genres born in the black community are forms of sociability and dissemination of black memory.

“When we talk about black Brazilian music, we are talking about a form of sociability that emanates memory in the voice. When I listen to Dona Ivone Lara or Jovelina Pérola Negra, the memory of the diaspora is present, and it’s not just because of the color of the skin”, says the researcher.

“That memory is still present today. It does not disappear and can be found in samba, funk and young people who revive black music. When we talk about black memory, we are talking about a culture that is very important and that does not disappear despite all racism, all unfair pressure from the radio industry and the idea of racial democracy. Black memory is present to this day, precisely because of the power that it is.”

For Peixoto, the black music in Brazil it can be seen as a continuation and evolution of the musical culture that already existed in the country, bringing new sound elements and addressing subjects that enriched Brazilian music. Furthermore, the movement strengthened the identity and visibility of the black community, despite resistance to foreign rhythms when they began to be broadcast on radio stations, which were popular at the time.

“Today they have a good relationship, but, at that time, black music was a reason for discord and revolt in Brazilian society, placing samba as something truly legitimate and authentic in our cultural expression. So, yes, black music suffered a lot of prejudice during that period, but it undeniably brought great influence”, he points out. “Today, we can observe an incredible legacy, through genres such as samba-funk, samba-rock and Rio funk itself.”

Given the 50 years of black music in Brazil, Dom Filó highlights this period as a moment of transformation, in which the black community made progress in the racial struggle, although they were not enough to deal with prejudice and discrimination in the country. “I had the honor and blessing of experiencing this transformation”, he celebrates.

“Today, I come across several generations and several people, including my generation, who were influenced by all this and bring this to the new generation. Today, we have answers. In my time, I had no references. The references were all negative. At school, in school books, in artistic representations, they were all negative. My generation experienced this transformation and my biggest hope is that the kids who are coming are aware that this process didn’t start now, it started way back.”

*Intern under the supervision of Vinícius Lisboa