October 26, 2024, 7:41 AM

October 26, 2024, 7:41 AM

“How do you tell the poor that God loves them?”

Whoever asked this question, as simple as it was forceful, shook up contemporary theology and revolutionized the teachings of the Church, with special relevance in Latin America.

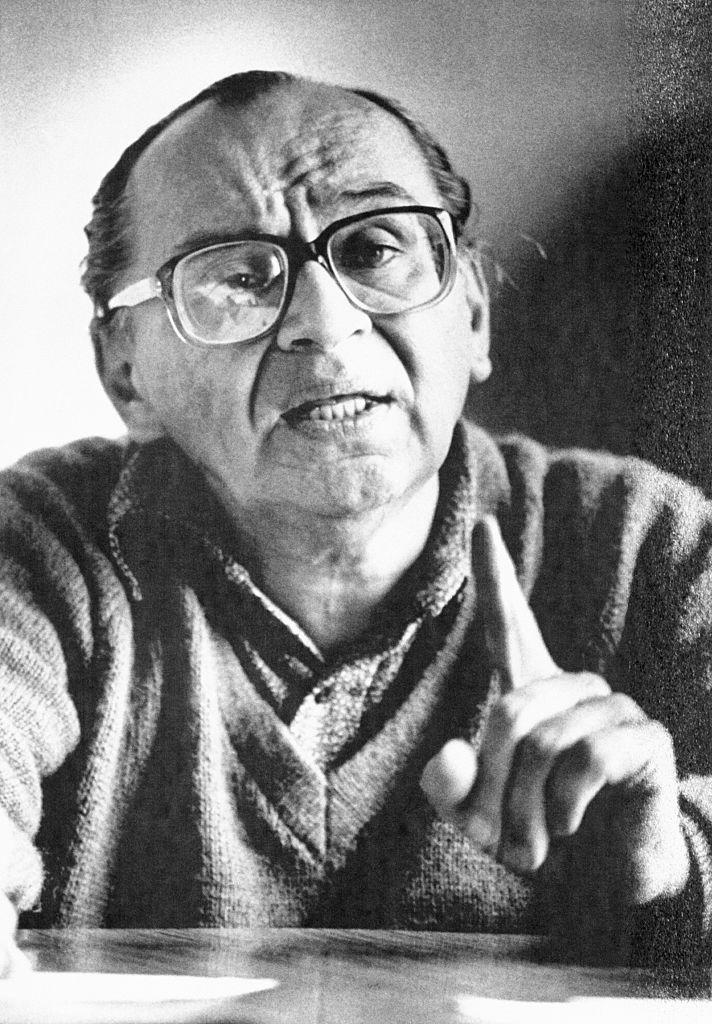

This is Gustavo Gutiérrez, a Peruvian priest, then 41 years old, who in 1969 captured that phrase along with other reflections in a pamphlet. Its title: “Towards liberation theology.”

The book became the fundamental work of, precisely, liberation theology, a social and political movement within the church that advocates an active role for the Roman Catholic Church in the fight against poverty.

Gutiérrez, theologian and Dominican friar, died this week at the age of 96 in his native Lima.

“The Dominican Province of San Juan Bautista of Peru regrets to inform that today, October 22, 2024, our dear brother Fr. Gustavo Gutiérrez Merino has left for his father’s house,” said a statement signed by Rómulo Vásquez, prior provincial of the order.

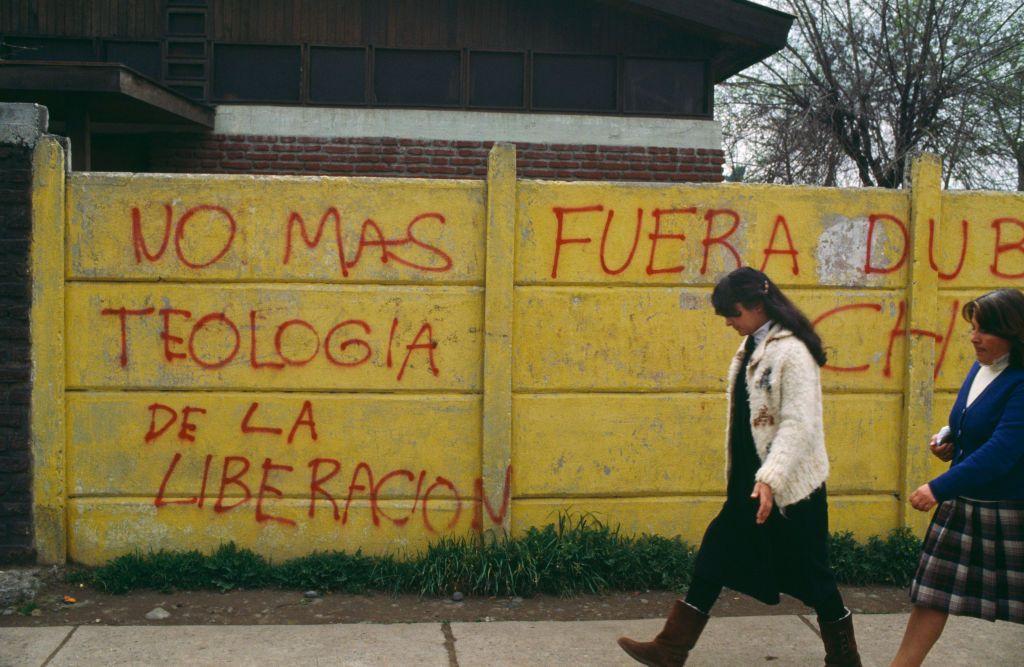

Their Progressive theories were adopted by many in Latin America, but they also encountered opposition and even disdain by more conservative voices within the Church.

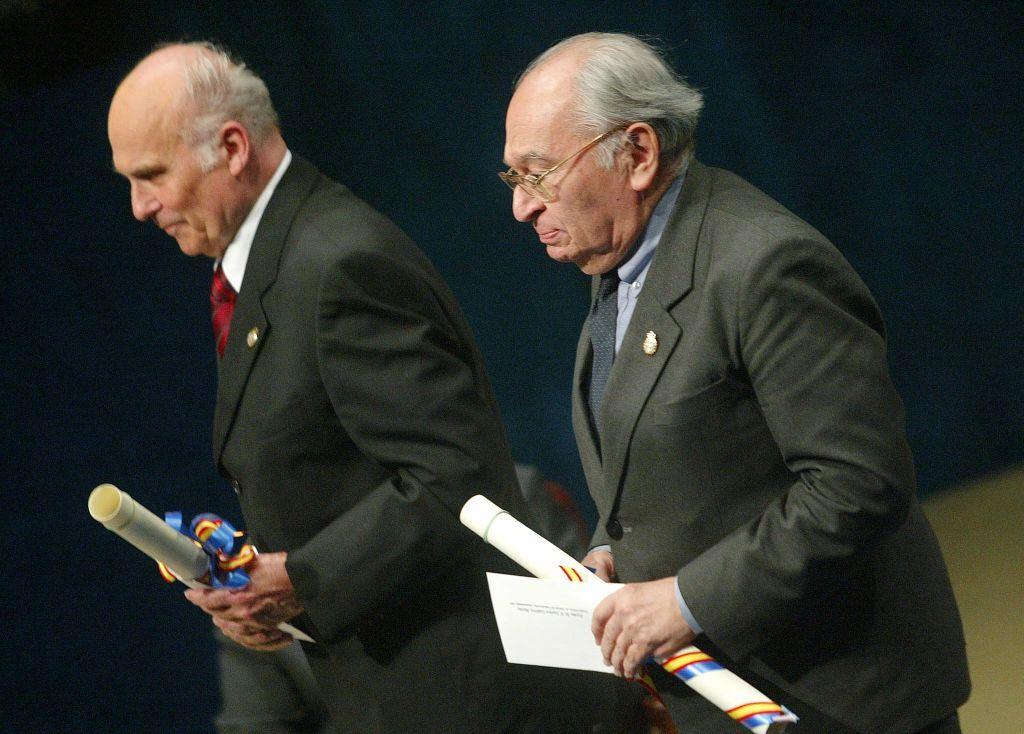

But although his beginnings were full of criticism, over the years his figure was restored and he received awards such as the Princess of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities (2003) together with the Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski or he was named Knight of the National Order of the Legion of Honor in France.

A “Marxist” theory

For Daniel Esparza, doctor in Philosophy of Religion from Columbia University and researcher at the Blanquerna Observatory of Religion, Communication and Culture, Gutiérrez “is a central figure in contemporary theologyand liberation theology, the first theological school in the history of Christianity that we can properly call American.

Until that time, theology was always influenced primarily by Europe.

With this movement, which began in the 1950s but was formulated by Gutiérrez in the late 1960s, religion is talked about from the perspective of the poor.

“Liberation theology supposes a praxis that seeks free the poor from structural poverty so that you can experience the fullness of life – a life that is understood as a loving gift from God. It is a solid project, biblically and politically speaking,” explains Esparza.

In the words of Gutiérrez himself in an interview he gave to BBC Mundo in 2003, “liberation theology was born in the second half of the 60s, which were not comfortable years. It was the time of the Tlatelolco massacre in Mexico , of the military dictatorship of Brazil, of the military government of Onganía in Argentina”.

“He always tried to raise awareness about the problems,” he added.

But, of course, this message was not so popular in some church groups and in the traditional sectors of politics on the American continent.

Before becoming a priest, Gustavo Gutiérrez studied Medicine and Literature in Peru, and then studied in Europe; specifically, Philosophy and Psychology in Belgium and Theology in France.

There he read the works of the German philosopher Karl Marx, author of “Capital” and “The Communist Manifesto”, the latter together with Friedrich Engels.

This, along with his vision of what the Church should be in the community, meant that his detractors often said that his emphasis on helping the poor was because he was a Marxist and they branded him a communist.

Thus, Gutiérrez and his theology received criticism from a figure such as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who later became Pope Benedict XVI.

The then cardinal feared that the “Marxist ideas” of liberation theology would foster rebellion and division, and even described them as a “fundamental threat to the faith of the Church.”

In the years following Gutiérrez’s publication that would shape the movement, many priests aligned with a radical current of liberation theology joined revolutionary movements, such as the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, which overthrew the dictatorial government of the Somoza family.

Neither the conservative sectors of the Church nor political sectors saw it favorably.

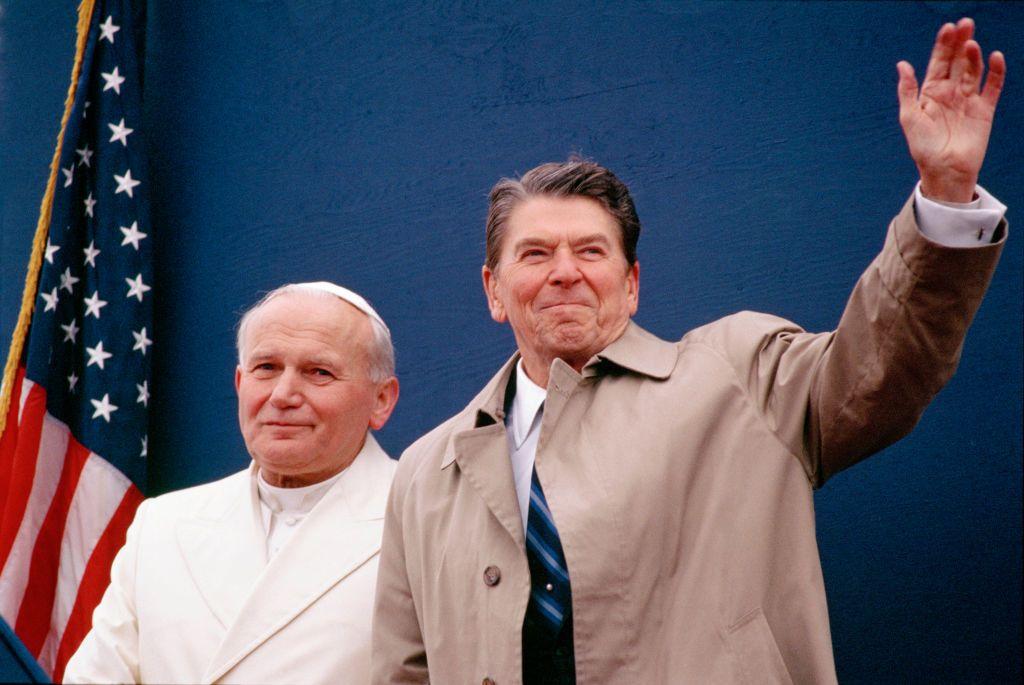

In the United States, the 80s began with a president like Ronald Reagan, a staunch fighter of communism. And everything that, in his opinion, sounded like that.

In the first Santa Fe Document He reacted against liberation theology and criticized it, saying that the Church had introduced more communist ideas than Christian ones..

The new ideas did not have the sympathy of Pope John Paul II either.

“Considering that the Polish pope was instrumental in the fall of the Soviet bloc, that he saw a threat of heterodoxy (theological and political) in any speech that could seem ‘Marxist’ was to be expected,” maintains Esparza.

“However, Gutiérrez himself never felt that he was ‘confronting’ anything – at least, that’s what Gutiérrez himself said.”

When Ratzinger became Benedict XVI, he even received Gutiérrez in Rome, “as if burying the hatchet” that had been sustained with the Vatican for so many years.

Then, With the arrival of Pope Francis at the head of the Church, they thawed somewhat more.

Father Gutiérrez praised Pope Francis for speaking of “a poor Church for the poor,” and in 2018, the pontiff sent Father Gutiérrez a letter for his 90th birthday.

The theologian and the neighborhood priest

Liberation theology, in the words of Gutiérrez, “It was born as a criticism made from within, because we were part of this Church and we wanted to live the Gospel authentically.”

That, as we are seeing, generated criticism.

“Any innovation is always received with a certain amount of resentment, especially when we talk about institutions that are at least 2,000 years old,” says Esparza.

And for this, he gives an important key that also shows the character that Gutiérrez was: “Doing theology from a Lima neighborhood without electricity or running water is not the same as from the library of the University of Tübingen (Germany).”

Because, despite being a theologian, “an accomplished intellectual, founding the Bartolomé de las Casas Institute, being a member of the Peruvian Academy of Language and a long etcetera, he was still a parish priest,” Esparza remarks.

His parishioners describe him as a “humble man with great ability to make friends”.

He combined his work as a professor and lecturer – a “born orator”, as Esparza was able to verify when he met him at an Ibero-American Congress of Philosophy in the early 2000s in Lima – with his work as a parish priest, officiant at weddings and retreats. .

Félix Grández, a Peruvian sociologist who met Father Gutiérrez at a spiritual retreat in 1978, said the priest radiated “a happiness that came from doing good, from his dedication to the poor.”

Grández told the BBC that one of the priest’s gifts was distilling theology into clear messages that appealed to young people, something he said he saw Father Gutiérrez do when he officiated at Mr. Grández’s own wedding and again at his daughter’s.

“He was well known as a theologian, but his way of connecting with people was by talking about chess, traditional music, movies and his support for the Alianza Lima soccer club.”

Another parishioner whom Father Gutiérrez married said she felt “immense gratitude for his life and everything he has contributed to the Church.”

And, always, they point out, with humility and feet on the ground. This is what he did during the years he was in the parish of popular neighborhood of Rímac, in Lima. And this is how he himself told BBC Mundo what he did there:

“There we have collaborated with a soup kitchen, medical care, but without getting our hopes up. These are things that have to be done, because there are immediate needs, but we must not think that this is going to transform society. What we have to do is go to the causes of poverty, and not just giving ‘aspirins’ for its effects.

Ideas from the Bible

Gutiérrez always maintained that his teachings were far from revolutionary, but rather deeply rooted in the Bible.

“Gutiérrez is deeply traditionalist. The biblical narrative is basically a story of sustained liberation. All revolutionary movements of the ancient world, including Christianity, had the same program of debt cancellation and redistribution of land and property rights. Gutiérrez simply takes this tradition and applies it to his concrete Latin American reality,” says Esparza.

The theologian himself said that, after being in Europe and returning to Peru, he found that the Church often “answered questions that the faithful did not ask themselves,” which implied that The Church hierarchy had distanced itself too much from the problems of its parishioners, especially in poor and disadvantaged areas..

He argued that the clergy had much to learn from the faithful in the poorest parishes who, he said, demonstrated day after day how hope can arise in the midst of suffering.

In his book “The Hermeneutics of Hope” he recalled how he had fought against a prevailing view among many faithful of the time that “we were born to suffer.”

“For many poor people in Latin America, their situation of poverty is a fatality. And they justify it even religiously. They believe they see the will of God behind it (…) What we have to do is go to the causes of poverty” , he said in statements to BBC Mundo.

In the letter that Pope Francis wrote to Gutiérrez for his 90th birthday, in 2018, he told him: “I thank you for everything you have contributed to the Church and humanity, through your theological service and your preferential love for the poor and those discarded from society.”.

And always, according to those who knew him, with an eternal smile on his face. It is not surprising that one of his life phrases was “no one is born to suffer, but to be happy.”

Subscribe here to our new newsletter to receive a selection of our best content of the week every Friday.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate them.