HAVANA, Cuba. – For many it may be difficult to believe that the singer-songwriter Ela O’Farrill (1930-2014) in the early 1960s she was censored, branded a “worm” and ostracized for composing a love song called Goodbye, happiness.

This song, which in 1962 became very popular in the performances of Elena BurkeDoris de la Torre, Bola de Nieve, Ela Calvo and the Aragón Orchestra, was considered “counterrevolutionary” by ridiculous censors who saw allusions contrary to the regime even in the soup and who could no longer think of what else they could prohibit.

One night, Ela O’Farrill was arrested in the lobby of the Saint John hotel in El Vedado, where she was singing with her guitar, alternating with José Antonio Méndez, and they took her to Marist Villathe headquarters of State Security. There, grim interrogators asked him about the people he associated with and what he was up to when making pessimistic and defeatist songs like Goodbye, happiness.

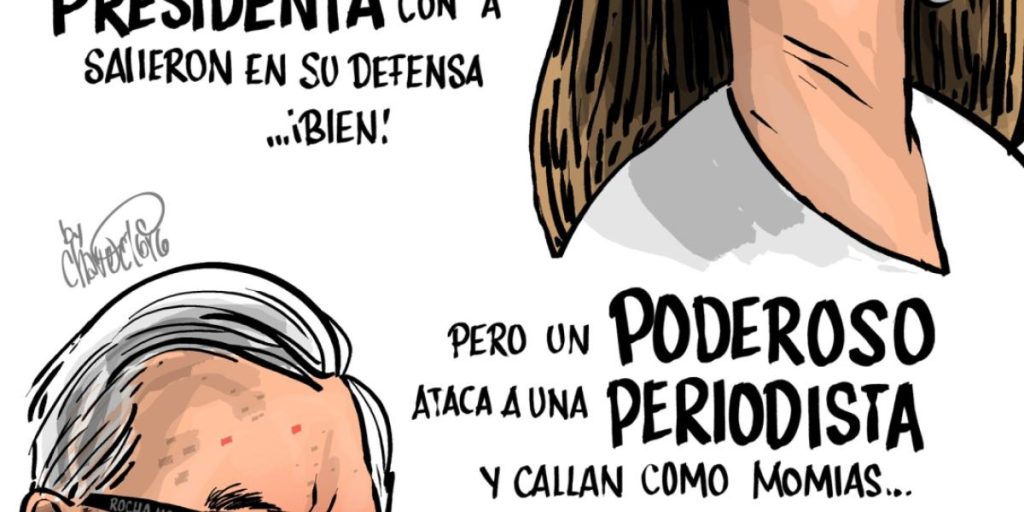

The Castro commissars considered it something suspicious and malicious that in Cuba in 1962 someone dared to sing “goodbye, happiness, I almost didn’t know you…”. You had to be happy with the Revolution, the promises of the Maximum Leader and with the bright future of socialism.

You had to be happy, regardless of the fact that Havana was filled with filth and military uniforms, that the boleros and the son were replaced by war marches, that there were numerous shootings, that the prisons were full, that the food was rationed and the empty store windows, that more and more families were broken up, and that the State controlled everything, absolutely everything, even who you slept with.

That happiness could not even be clouded by the fact that the country was on the verge of being annihilated due to the “commander in chief”’s decision to allow the Soviets to install Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba…

Even so, you had to be happy, there could be no room for sadness. Those who did not show joy and enthusiasm in daily work and the fulfillment of “the tasks of the Revolution” were frowned upon.

The joy had to be expressed, in the classrooms, the workshops or on board the trucks that led to volunteer work, to any military mobilization or to the Plaza of the Revolution. Smiling, they had to chant mottos and slogans and applaud loudly to receive the bosses on their tours, and sing songs, like that horrible “bon bon chia” that no one knows who invented, to flatter the most prominent in socialist emulation or the who, for any reason, received a diploma or a medal.

The State-Party-Government that eliminated Christmas, decided that the subjects would get drunk and drink soup from a collective pot on the anniversaries of the attack on the Moncada barracks and the creation of the CDR; or when they celebrated imitations of carnivals, so that, beer in hand, they would roll to the beat of the Santiago conga, and shake with the Mozambique and The tired ox.

Anyone who did not join the official celebrations was frowned upon, taken into account by those responsible for monitoring the CDR, and his name was added to the list of those who were apathetic and possibly disaffected.

The regime also decided when it was appropriate to stop the revelry and become mournful and solemn to honor “the martyrs of the Revolution” or the leaders who were dying of old age.

In recent decades, no matter how hard they try, the leaders have not been able, in the midst of so much disaster, to fulfill their calls for enthusiasm and joy. That is only seen in the Television Newscast.