October 4, 2024, 7:35 AM

October 4, 2024, 7:35 AM

Would you sacrifice one person to save five? It is the question of the typical tram dilemma, in which a short-circuited train hurtles uncontrollably onto five people working on a track.

It has been seen that different characteristics of moral dilemmas lead to different answers.

A response that is acceptable to many people is to pull a lever to divert the train to another track where only one person is working.

It’s what It is called a utilitarian response, because it is based on the lesser evil.

We accept the death of one worker to prevent five of them from dying.

The tram dilemma has another version, in which the options are either to let the tram continue its course and run over the five people working on the track, or to push a single person onto the track so that the train derails sooner. .

This second option carries a more personal implication than pulling a lever, so this version of the dilemma usually results in a deontological response: most people decide to do nothing and let the wagon run its course.

As these are two different ethical approaches, there is really no right answer.

The answer depends on each person’s cost-benefit assessment.

For example, religious people tend to give a deontological response, perhaps because voluntarily doing harm is more costly than letting “whatever God wants.”

In some variants of the dilemma it could also be that the person alone on the road is someone loved, and then the cost-benefit evaluation also changes.

The characteristics of each person also influence these decisions.

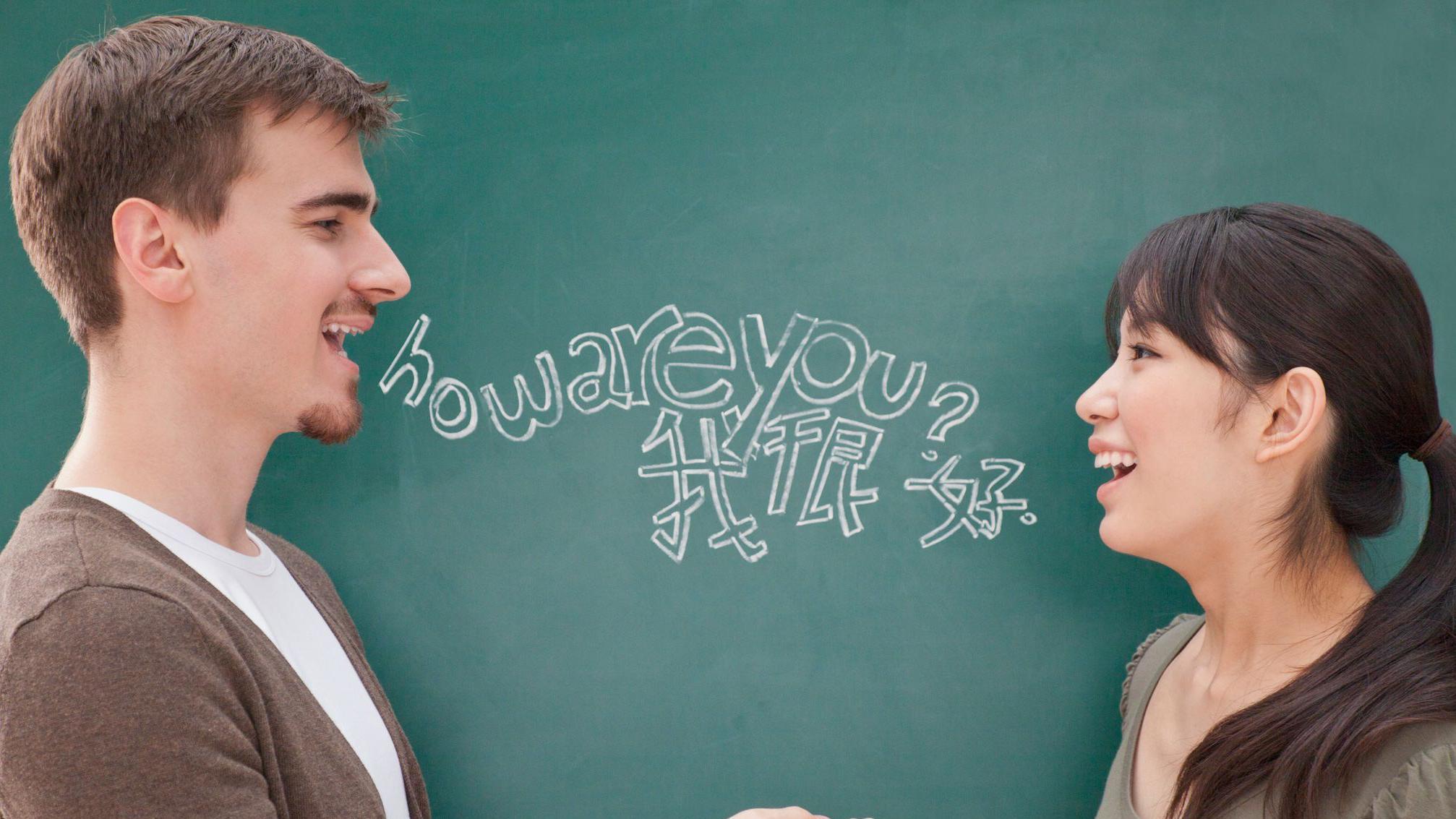

For example, bilingual people have been found to respond differently depending on whether they use their first or second language when faced with a moral dilemma.

If the dilemma is presented to them in their native language, they tend to give a deontological response.

Instead, in their second language they tend to respond in a utilitarian way.

Second language effect

This “foreign language effect” happens even when people have learned the second language at a very young age.

It also occurs in related languages, such as Italian and Venetian.

Our research group carried out a study to elucidate whether this also happens with another pair of Romance languages. Specifically, in Catalan-Spanish bilinguals.

All participants in our study considered that their mother tongue (L1) was Catalan and that they had a second language that, although acquired early, was not native (L2, Spanish).

Thus, we presented the participants with a series of moral dilemmas similar to the famous trolley dilemma.

As we have anticipated, based on different factors (such as personal involvement), The same dilemma can have different versions.

Thus, different versions of a dilemma could be shown in each language.

Surprisingly, we did not find a significant difference in moral decisions made in Catalan compared to those made in Spanish.

Our findings suggest that Catalan-Spanish bilinguals do not exhibit the second language effect.

Psychopathic Personality Traits

There is a hypothesis that we take greater emotional distance in a second language.

It is possible that this has to do with the specific ability or competence in that second language, but in our study it is not clear.

Although the participants acquired their second language early and were highly proficient in both languages, there were significant differences between the linguistic proficiency of their second language compared to their native language.

So what other variables might have to do with greater emotional distance?

Our study examined the influence of psychopathic personality traits on moral decisions. Boldness, disinhibition and malevolence were evaluated.

These personality traits are present in all people, without necessarily being considered psychopaths.

For example, who most of all has ever been ahead in line at the supermarket or insulted someone, right? This lack of empathy, when we give more importance to our time or hurt someone, even verbally, has to do with malevolence.

In this sense, our study shows that this malevolence is significantly associated with a higher proportion of utilitarian decisions, regardless of the language in which the dilemma is presented.

This aligns with previous studies suggesting that people with higher psychopathic traits are more likely to make utilitarian decisions, prioritizing the greater good over individual harm.

Dilemma variables

Furthermore, our study explored how differences between dilemmas could determine different moral decisions.

For example, dilemmas may be perceived as more or less plausible, or be more or less disturbing to those who read them. Thus, more troubling dilemmas, perceived as more vivid and realistic, were more likely to lead to utilitarian responses.

This happened particularly in people with higher scores in malevolence.

Other results of our study emphasize the importance of considering personal involvement, which we have already commented, but also other characteristics of dilemmas.

For example, dilemmas worded in such a way that the protagonist saves herself with her action (own benefit) obtain a higher percentage of utilitarian responses.

It also happens when the injured person was going to die anyway (inevitable death).

All these results are in line with previous studies carried out with this type of dilemmas validated in many languages.

Importance of context

The absence of the second language effect in early Catalan-Spanish bilinguals could be attributed to the close linguistic and cultural relationship between Catalan and Spanish.

Both are Romance languages used interchangeably in most social and educational contexts on the island of Mallorca.

Could it be that this linguistic wealth “protect” to Majorcan people from the effect of the second language? It is a hypothesis to test in future research.

For now, our study provides new data on the factors that influence moral decision making.

It highlights the role of personality traits such as malevolence in responding to moral dilemmas. It also remembers the role of language and the factors inherent to the dilemma or perceived by the reader.

Although we are not fully aware, our response to moral dilemmas depends not only on our reasoning, but also on our emotions, our language and our personality.

Knowing this may not lead us to make better decisions, because some are not more correct than others, but it could help us understand our responses.

*Albert Flexas Oliver, Daniel Adrover Roig, Eva Aguilar Mediavilla and Raúl López-Penadés are professors of psychology at the University of the Balearic Islands.

This article appeared on The Conversation. You can read the original version here.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate them.