August 25, 2024, 7:59 AM

August 25, 2024, 7:59 AM

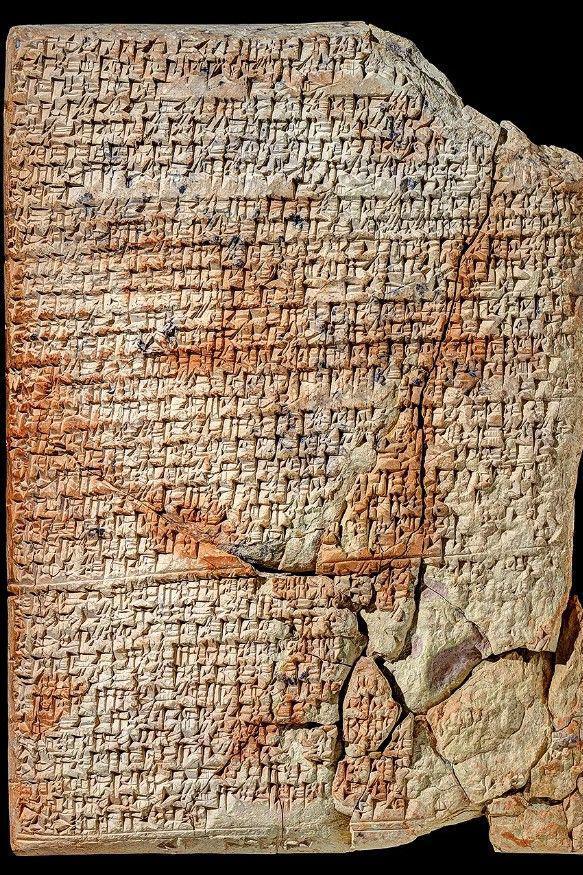

No one knows exactly where they came from and for a long time no one really understood what they were saying.

Scholars at Yale University thought the small clay slabs covered in dense cuneiform script – one of the longest-lived writing systems in human history – contained a list of medicines.

Unearthed in an archaeological dig in the Middle East, they have probably been in the Yale Babylonian Collection since 1911. However, it was not until the early 1980s that French scholar Jean Bottéro finally discovered what the tablets said.

In their own discreet way, for nearly 4,000 years, these four plates have been talking about dinner.

The three largest are the size of a large bar of soap, the smallest, more than a thousand years younger, is a simple round handful of clay.

They all have the ingredients engraved on them, not of pharmaceutical products but of dishes. Dating back to at least 1730 BC, the three largest tablets mostly contain descriptions of stews; the smaller, later one, describes broth.

The very fact of its existence is a mystery. In ancient Mesopotamia, people rarely wrote about food preparation, explained Agnete Lassen, deputy curator of the collection.

“Out of hundreds of thousands of cuneiform documents, these are the only food recipes that exist,” he said. “We don’t have an explanation.”

In fact, when ancient scribes placed a stylus into clay and recorded stories and tales that mentioned food, used words that are sometimes mysterious to modern scholars.

They appear ingredients that still cannot be identified todaysaid Gojko Barjamovic, an Assyriologist at Harvard University. “Asum” is myrtle, “salu” are cress seeds, but what is “hurrium”?

Just read the list of unknown spices cited in an article by Barjamovic, Lassen and their collaborators, conjures up visions of a lost garden, nestled between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers: Kurullu, kuruš, nīnu. Silaru, zanzar, zibibianu.

The Yale Culinary Tablets, as the four clay slabs are known, assume many things in the same way that modern recipes do: the writer expects the reader to basically already know how to make them.

The instructions are concise and short. And as with many old recipes, no quantities are specified.

Following the recipe

So, given all of this, it can be difficult to clearly imagine what food or the dining experience was like in Babylon long, long ago.

But a few years ago, Barjamovic, Lassen and their colleagues, including Iraqi food historian Nawal Nasrallah, made some progress in that direction. They updated recipe translations by Jean Bottéro using new interpretations of some words and made careful experimentation, trying out the ingredients in the recipe one by one.

They eliminated one of the possible ingredients that made the resulting dish unbearably bitter, to the point that none of the other carefully incorporated seasonings were detectable.

While it is possible that this was the desired effect, it does not seem likely.

It is striking, however, that Stews and broths make up the totality of the recipessaid Nasrallah, author of the cookbook “Delights from the Garden of Eden.” Stew (meat and vegetables in broth) is a staple of modern Iraqi food.

It was also an important feature of food in medieval Iraq, as described in a 10th-century cookbook that Nasrallah translated.

And when the research group cooked the recipes Of the four culinary tablets, they produced something that must at least evoke that ancient tradition.

Copying the recipe

This is how one of the stews is made: for the lamb stew known as tu’hu, First, you get water. Then you brown the leg meat with some kind of fat.

It is put salt, beer, onion, arugula, cilantro, shallot, cumin, beetroot and more water. Then crushed leek and garlic, more coriander to give it a spicy flavour. Then add the kurrat, an Egyptian leek.

Beets give it an electric red color, and of the four, it’s Lassen’s favorite recipe. “It’s spicy and very well seasoned,” she said. “It has good flavors.”

Even with all this careful processing, the fact remains that people’s tastes might have been quite different back then.

A famous example of A food that is no longer so popular is the Roman fish sauce garum: This potent, fermented umami substance is not a common part of modern Italian cuisine.

Researchers recognize this difficulty: using the tastes and impressions of people living today to Trying to establish the flavour of these ancient dishes is a tricky business.

Between then and now, Islam also reached the Middle East, making pork a less popular ingredient, and the so-called “Colombian exchange” (as trade between America and Europe was called since the 15th century) He brought tomatoes, eggplants and potatoes from the New World. Modern Iraqi cuisine is not a replica of what was eaten in Babylon.

Who knows if in 3,000 years people will be eating something similar to what you eat today? In a modern food system where What we eat does not particularly depend on where we areit seems that the connection between food and local geography has evaporated.

In thousands of years, after who knows what changes, perhaps that link will have returned. Perhaps the climate will be so different that lentils will be grown in the British Isles. Perhaps there is a booming business in coconuts in what was once Siberia.

Barjamovic notes that when it comes to these ancient recipes, the story is not over either. Each season of archaeological work brings with it the possibility that new texts will be unearthed, shedding new light on mysterious words for spices and other ingredients.

The Mesopotamian way of thinking was not copied or transmitted as the Greek texts were. It disappeared from human knowledge in the first century BC. “But since they wrote on clay,” he said, “it is there, indestructible.”

*This article was published on BBC Future. You can read the original article here following this link.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate them.