“Without autonomy there are no inflation targets with chances of success”stated the Brazilian economist, Alexandre Tombini.

The goals of inflation as a monetary policy regime -a scheme that is about 30 years old in the world-, was the main theme of the conference offered on Friday in Montevideo by the former president of the Central Bank of Brazil, and current representative for the Americas of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS for its English acronym)

In his presentation, Tombini said that after the general increase in inflation in the countries of the region, and despite having “reached a ceiling”, the new phase of decline “will be a gradual process that will take time.”

Without mentioning specific cases in any country, the Brazilian economist also stated that there is a risk that “high inflation will remain persistent.” This is associated with the unanchoring of expectations, indexing mechanisms and wage increases above productivity.

Tombini summarized the importance of lowering inflation in the distortions it generates in the economy, and because it is a “highly regressive” tax that hits low-income sectors more.

The expert highlighted that the vast majority of advanced and emerging economies today have inflation targets. Among its advantages, he highlighted that it is a system that “helps build credibility”, that it has been successful, and that it it is “flexible” and can adapt “to tomorrow’s challenges”.

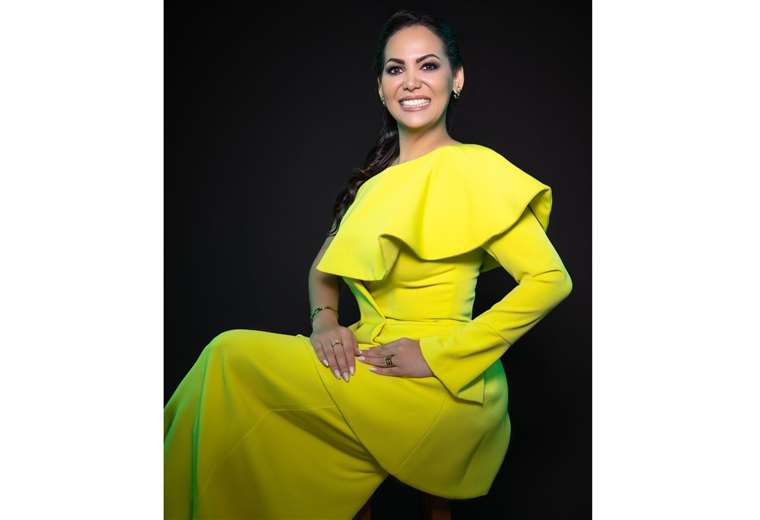

Ines Guimaraens

Tombini spoke about the advantages of the inflation targeting system.

Uruguay and its “comfort zone”

Uruguay has inflation targets since 2005. However, that indicator has been persistently outside the targets, and by average figures of 8% per year.

After Tombini’s presentation, the economists Diego Pereira, Tamara Schandy, Nicolás Cichevski, and Aldo Lema raised some thoughts on this topic.

Lema considered that for a small and open economy, the inflation targeting scheme is the “least bad”, above “some slowness” to fully incorporate it that has occurred in Uruguay.

The economist stated that the main problem in Uruguay has been that “the true objective”, which he called the “comfort zone”, has been located at 8%, and it is there where the expectations of the agents have been aligned.

“We could also conclude that there is a certain punishment for society as a whole when inflation jumps above 10%, and when it falls below 6% there is a temptation to have expansive policies to achieve some real effect in the short term or affect activity” , he claimed.

In this line of reasoning, the economist stated that “there has not been a sufficiently autonomous Central Bank, neither in fact nor in law.” And he added that “all governments have been tempted to aim at 8%, since it does not exceed 10%”, without “doing what had to be done” to reduce inflation to levels of between 3% in the short term and 4%.

“An important part of the problem is because of that convenience with that supposedly innocuous 8%, but that has costs,” Lema highlighted.

Pereira generally agreed with Lema’s statement, and also highlighted that in previous years there were periods in which monetary policies “were not aligned with quasi-fiscal policies” and exchange intervention processes “that were not always aligned” with the objectives of minimize volatility. He also mentioned the fact that the positions of the bank’s Board of Directors do not transcend the change of government authorities.

For his part, Cichevski agreed that there is a “comfort zone” located between 6% and 10%, because “there is no demand from the population to have a lower inflation level.”

From his point of view, the indexation rules, both for salaries and contracts, “end up conspiring” not only against monetary policy to lower inflation, but also with that public demand. “In general, both companies and workers do not perceive the benefits that inflation of 2%, 3% or 4% could have,” he said.

Ines Guimaraens

The conference was organized by the Central Bank.

The “policy alignment”

The economist Schandy considered that there were moments in the past where monetary policy was “inexplicably lax” in the face of inflation levels on the axis of 8%, with negative real interest rates until the 2008 financial crisis, and an average of 1% between 2010 and 2013, when the economy was growing strongly and inflation was off target.

“The lack of full consistency in the use of the instruments with respect to the goals also makes it difficult to know and have evidence of how effective monetary policy is with those instruments,” he said.

On the other hand, he pointed out by way of example, that the non-tradable portion of the CPI “has never been” within the target range in the last 15 years, and that more than 80% of the time it has been above 8%.

“It is like a very strong verification that there is interaction with salary, fiscal policy. (…) This leads to a genuine debate about what mandate the Central Bank has to bring inflation to the center of the target range, when in reality there is no full alignment with the rest of the policies”, pointed.

salary negotiation

By way of example, Schandy wondered what happens if the new round of salary negotiations sets “relatively high” guidelines in relation to the official goal of the BCU.

“If the inflation projections on which salary increases are based are not the axis of the target range, it is difficult to think that the political system is going to give the Central Bank the autonomy to pursue such an aggressive inflation target, when at the same time validates salary indexation mechanisms”, said.

The intention that the authorities had of bringing inflation to 3.7% in 2024 was abandoned in 2022, when the MEF proposed a new target of 5.8% in the Accountability. With this, inflation would be within the target range (3% to 6%) in the last year of government. Meanwhile, private sector economists project it at 6.7% for that year, that is, above the ceiling of the target range.