May 14, 2023, 8:11 AM

May 14, 2023, 8:11 AM

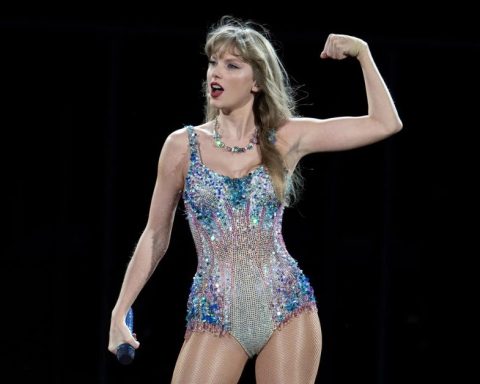

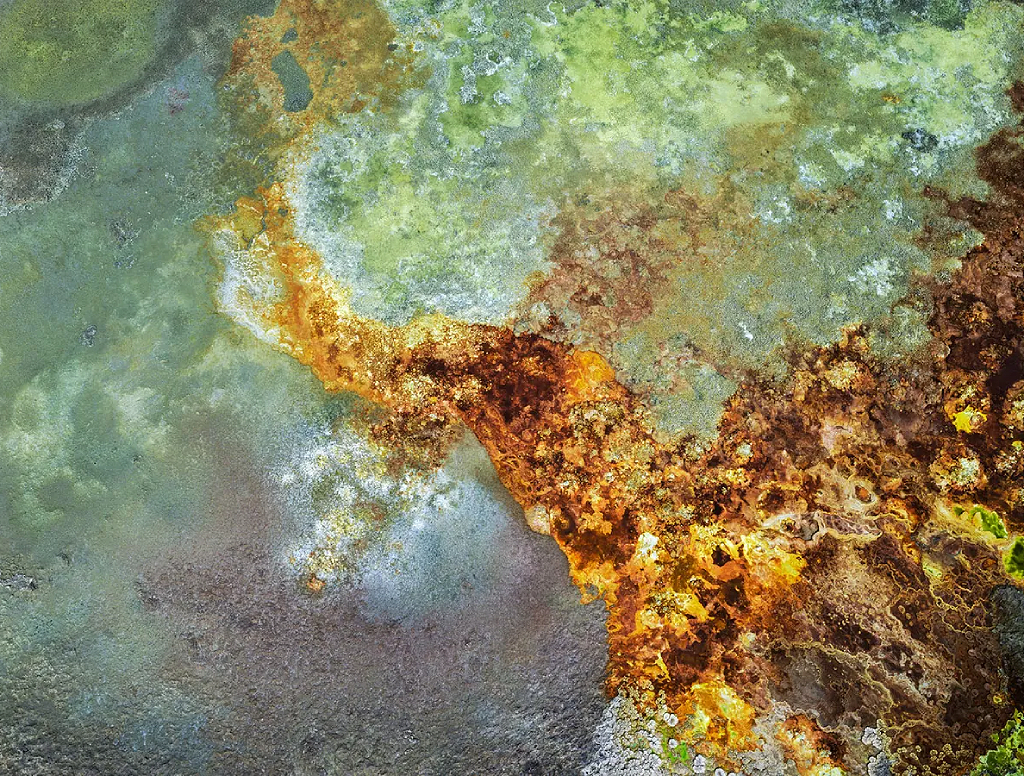

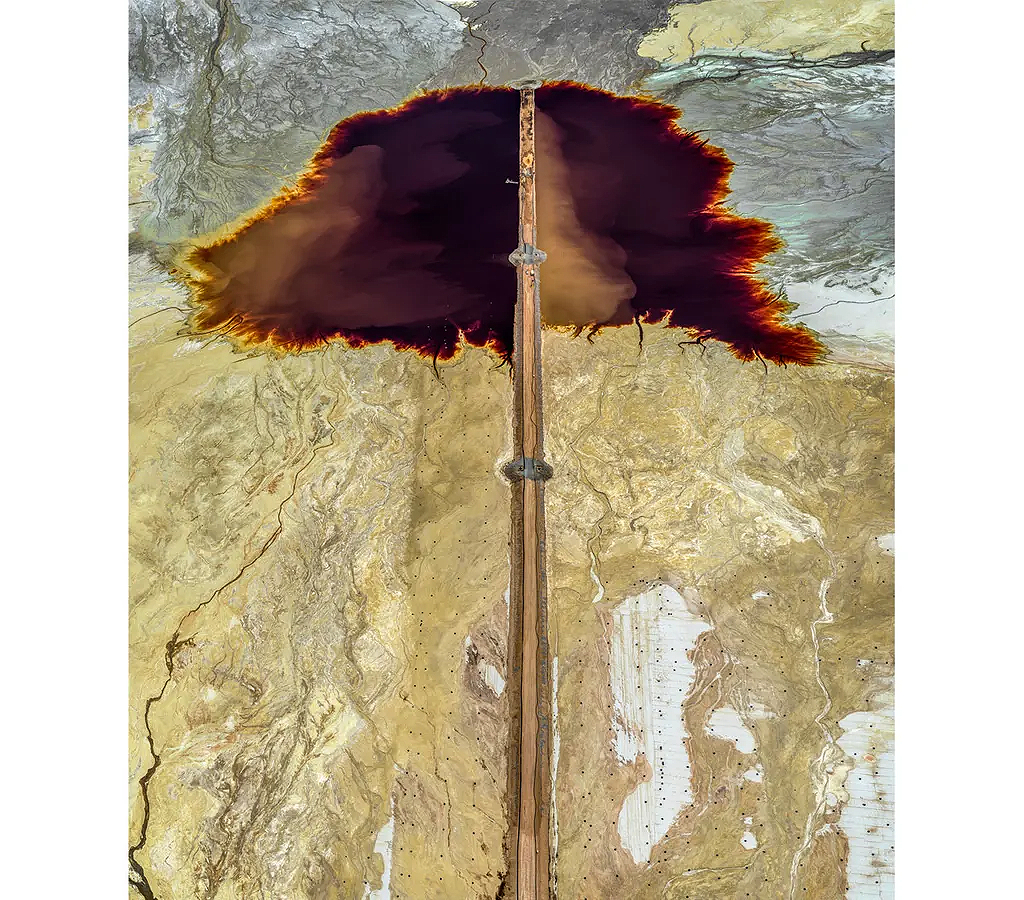

For more than 40 years, Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky has recorded the impact of humans on Earth in large-scale images that often resemble abstract paintings.

The writer Gaia Vince, whose book “Nomad Century” was published in 2022, he interviewed Burtynsky for BBC Culture about his latest project, African Studies, which are now collected in a book.

All images credit: Edward Burtynsky, Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto/Flowers Gallery, London

With your photos we have seen the results of our consumption habits or our lifestyles in our cities, as well as in natural landscapes. Can you tell me about African Studies?

I read that China was starting to operate in Africa, and I thought it would be very interesting to follow what was happening.

It has been a decade long project, researching and then photographing in 10 countries. I started in Kenya, then Ethiopia, then Nigeria and then South Africa.

Tell me about your experience in the Danakil depression, in Ethiopia.

All of our drone equipment didn’t work because we were 400 feet below sea level. The drone’s GPS said: ‘You’re not supposed to be here. You are at the bottom of the ocean.’

The Danakil Depression is a vast area covering about 200 km x 50 km. It is one of the hottest places in the world and is known as “hell on Earth”.

I have never worked in temperatures above 50 °C. At night it was 40°C, even that is almost unbearable. We slept outside because there are no buildings, there are no interior spaces.

We were there for three days photographing; every morning we would drive up to 25 kms to go to the locations.

One of them was Dallol, a volcanic hell of sulphurous springs. Getting there required us to lug all of our heavy gear up while climbing jagged rocks for about 1.5 km.

Africa is the last major continent with large amounts of wildlife left. Partly due to colonialism and other extractive industries of the global north, the industrial revolution in Africa is happening now. How do you see it?

The African continent has a lot of desert left and there are a lot of resources, like the oil discovery in Tanzania and in northern Kenya and other places.

There is a great rush to install pipelines, particularly with the involvement of China.

And many maneuvers to build infrastructure in exchange for access to resources, be it farmland for food security, or oil, yellow cake (uranium oxide), etc.

It’s like economic colonialism: I don’t think they want full control of these countries. They want an economic advantage, your resources and the opportunity they provide.

For example, the Chinese have the largest deposit of yellowcake on the entire African continent: I photographed that mine.

I also saw your amazing photos of the shoe factory in Ethiopia. It seems completely transposed from China to Africa.

Some of the photos were taken in Hawassa, which is an 80,000m2 Special Economic Zone, like Shenzhen in China.

The Chinese built 54 sheds, roads, lighting, plumbing… everything, from start to finish, in one year.

All the structures were brought by ship and then by rail to Ethiopia and erected as a Meccano set.

And when I went, they were filling those sheds with sewing machines and weaving machines.

The industrial revolution started in England and the factories of the global north, and then that moved to poorer countries… Now it’s affecting Africa. But where will he go next? There is no other place.

I often say that ‘this is the end of the road’.

They had to leave China because they are choking on pollution, and the workforce said, ‘I’m not going to work for such low wages anymore.’

So the Chinese are training textile workers, mainly women 16, 17 years old, in Ethiopia and Senegal.

In a matter of two or three months, these girls, separated from their families, are stuck in a workshop behind sewing machines and at par with Chinese production rates.

Deep down your images are very political, right?

I have been following globalism but started with the idea of just looking at nature.

I started with ‘who is paying the price for our population growth and our success as a species?’

Generally speaking, it is nature. They are the animals, the trees, the grasslands, the wetlands, the oceans; that’s where the price is paid.

They are all the natural environments of the planet that we used to coexist with, but that we are overwhelming.

So nature is at the center of all my work, which is really a kind of prolonged lament for the loss of nature.

Do you see yourself as an activist, are you trying to bring about change?

I wouldn’t say activist. Someone once said ‘artivist’ and I liked that better.

‘Activist’ seems to lean more towards direct political discourse: I don’t want to turn my work into an accusation, some kind of two-dimensional blunt tool to say, ‘This is wrong, this is bad, cease and desist.’ I don’t think it’s that simple.

I’m trying to show parts of our world that are developing every day to support what is now 8 billion people, wanting to have more and more of what we have in the West.

I understood 40 years ago, when I started looking at population growth and had a chance to see the scale of production, that this would only get bigger.

I decided to continue looking at human expansion, how we are reaching out to the whole world, pushing back nature, but we live on a finite planet.

I think the term ‘revealer’ versus ‘accuser’ has always made me feel more comfortable, in that I’m pulling back the curtain and saying, ‘Look, we can still turn this ship around if we’re smart. We are betting the planet’.

Photography makes everything sharp and present at the same time.

Seeing my work to scale, like big prints, you can walk up to them and you can look at the tire tracks and you can see the little truck or the person working on the corner.

youYour photos are very pictorial. Do you see yourself more as an artist or more as a photojournalist?

I walk that line. What I share with photojournalism is that there is a narrative behind it.

I would say my rudder is art, but everything I’m photographing is tied to this idea of what we humans are doing to transform the planet, so that’s the overall narrative.

He also photographs some natural landscapes, and often landscapes, such as repeated circles of agricultural monocultures, that appear natural because they have patterns that occur in plants and natural river systems.

I start from art, so I look for historical references to art, be it abstract expressionism or other ideas shared with painting.

I look at a particular topic and then spend time on how to approach it.

If Abstract Expressionism had never existed as a movement, I don’t think I would have made these images.

We live in a human-altered world, but we depend on Earth for everything and we are all interconnected. I wonder how far a photograph can go to explain that complicated concept of interconnectedness.

One of the things that photography and documentary film can do is reveal that over and over again.

It can show you places average people wouldn’t normally go and bring you to the areas we all depend on.

People can absorb information better than reading – images are really useful as a kind of turning point for a deeper conversation.

I don’t think they can give answers, but they can certainly lead us to awareness, and awareness is the beginning of change.

With my photography, I observe, and my work has never been about the individual, it’s been about our collective impact.

* To read the interview originally published by BBC Culture, Click here.

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC Mundo. Download the new version of our app and activate them so you don’t miss out on our best content.