López was one of 13 Mexican journalists killed in 2022, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), a New York-based human rights organization.

It was the deadliest year on record for journalists in Mexico, now the most dangerous country for reporters in the world outside war-torn Ukraine, where CPJ says 15 journalists were killed last year.

A day earlier, López – who ran two online news sites in the southern state of Oaxaca – had posted an article on Facebook accusing local politician Arminda Espinosa Cartas of corruption related to her re-election campaign.

As he lay dead, a nearby patrol car responded to an emergency call, intercepted the van, and took the two men into custody. Later it was learned that one of them was the brother of Espinosa, the politician in López’s story.

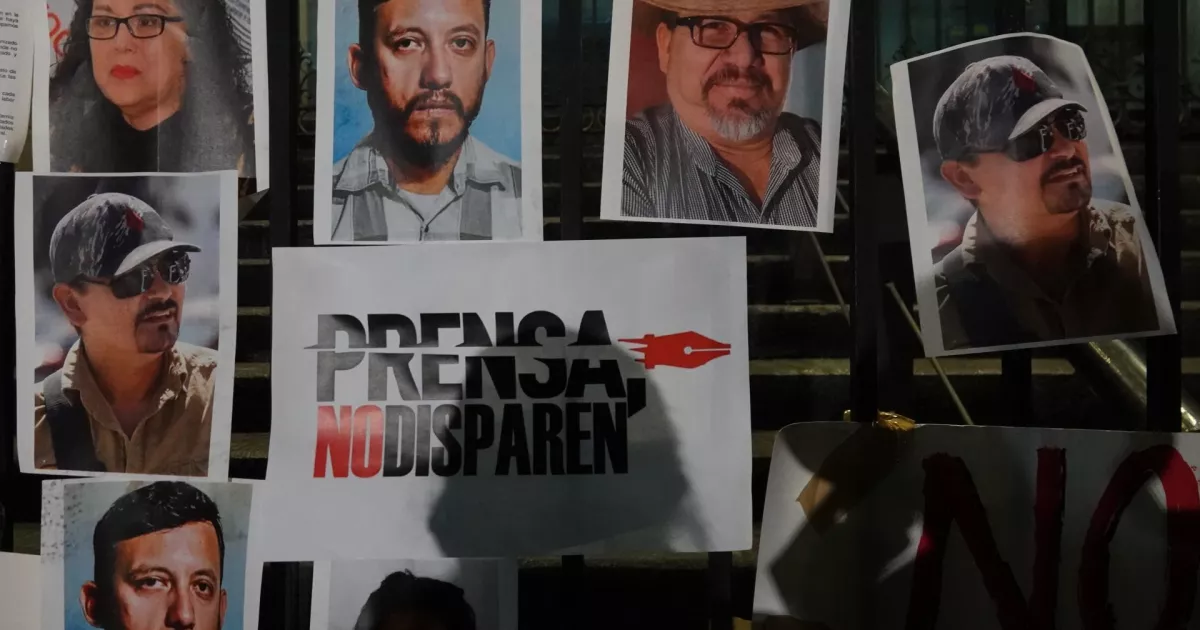

(Juan José Estrada Serafín/Cuartoscuro)

Espinosa has not been charged in connection with Lopez’s murder. She has not responded to multiple requests for comment and Reuters he has not been able to find any previous comments from him on his role in the possible corruption or on the Lopez story.

His brother and the other man remain in detention but have not yet been tried. His attorney did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

“I stopped covering drug trafficking and corruption and Heber’s death still scares me,” said Hiram Moreno, a veteran Oaxacan journalist who was shot three times in 2019, suffering leg and back injuries, after writing about drug deals in local criminal groups.

His attacker was never identified. “You can’t count on the government. Self-censorship is the only way to keep yourself safe,” she lamented.

It is a pattern of fear and intimidation that is repeated throughout Mexico, after years of violence and impunity that have created what academics call “zones of silence” where murders and corruption remain unchecked and undocumented.

“In the quiet zones, people don’t have access to basic information to lead their lives,” said Jan-Albert Hootsen, CPJ’s representative in Mexico.

“They don’t know who to vote for because there are no investigations into corruption. They don’t know which areas are violent, what they can say and what not, so they keep quiet,” he added.

The spokesman for the Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, did not respond to a request for comment about the attacks on journalists.

Since the start of Mexico’s drug war in 2006, 133 journalists have been killed for reasons related to their work, CPJ found, and another 13 for undetermined reasons. In that time Mexico has registered more than 360,000 homicides.

Attacks against journalists have spread in recent years to previously less hostile areas such as Oaxaca and Chiapas, threatening to turn more parts of Mexico into information dead zones, say rights groups including Reporters Without Borders and 10 local journalists.

López was the second journalist to be murdered since mid-2021 in Salina Cruz, a Pacific port in Oaxaca.

It is located on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, a strip of land connecting the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific that has become a landing point for chemical precursors to make fentanyl and methamphetamine, according to three security analysts and a source from the DEA.

López’s latest story, one of several he wrote about Espinosa, covered alleged attempts by politicians to get a company building a breakwater in the port of Salina Cruz to threaten workers into voting for it or otherwise Otherwise, they would be fired.

The infrastructure is part of the Interoceanic Corridor, one of López Obrador’s flagship development projects in southern Mexico.

José Ignacio Martínez, a crime reporter on the isthmus, and nine of López’s fellow journalists say that since his assassination they have become more afraid of publishing stories that delve into the corridor project, drug trafficking and state collusion with organized crime.

A media outlet you spoke to Reuterswho asked not to be named for fear of retaliation, said he had done some research on the broker but did not feel safe to publish after Lopez’s death.

López Obrador’s spokesman did not respond to a request for comment on the corruption allegations related to the broker.

In 2012, the Government created the Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists. Known simply as the Mechanism, the agency provides journalists with panic buttons, surveillance equipment, home police custody, armed guards and relocation.

Since 2017, nine reporters protected by the Mechanism have been killed, CPJ found.

Journalists and activists can request protection from the Mechanism, which evaluates their case together with a group of human rights defenders, journalists and representatives of non-profit organizations, as well as officials from government agencies that make up a governing board.

According to the analysis, not everyone who requests protection receives it. There are currently 1,600 people registered with the Mechanism, including 500 journalists.

One of them was Gustavo Sánchez, a journalist murdered at point-blank range in June 2021 by two hit men on a motorcycle. Sánchez, who had written critical articles about politicians and criminal groups, enrolled in the Mechanism for the third time after surviving an assassination attempt in 2020. Protection never came.

The Oaxaca prosecutor said then that Sánchez’s coverage of local elections would be one of the main lines of investigation into his murder. No one has been charged in the case.

Sánchez’s murder led Mexico’s Human Rights Commission to prepare a 100-page investigation into the failures of the authorities. The tests “revealed omissions, delays, negligence and breach of duty by at least 15 public servants,” according to the report.

Enrique Irazoque, head of the Department of Defense of Human Rights of the Ministry of the Interior (Segob), said that the Mechanism accepted the conclusions, but highlighted the role that local authorities played in the lack of protection.

Fifteen people from the government and civil society told Reuters that the Mechanism lacks sufficient resources for the size of the problem. Irazoque agreed, though he noted that his 40-person team increased last year to 70. His 2023 budget increased to about $28.8 million, up from $20 million in 2022.

In addition to insufficient funding, Irazoque said that local authorities, state governments and the courts must do more, but that the political will was lacking.

“The mechanism is absorbing all the problems and the issues are not federal, they are local,” he told Reuters.

Irazoque believes more convictions are needed most, as the lack of legal repercussions for public officials encourages corruption.

Impunity for the murders of journalists is around 89%, according to a 2021 report by Segob, which oversees the Mechanism. According to the report, local public officials are the main source of violence against journalists, ahead of organized crime.

“One would think that the biggest enemy would be the armed groups and organized crime,” said journalist Patricia Mayorga, who fled Mexico after investigating corruption. “But it’s really the ties between these groups and state officials that are the problem,” she stressed.

Many slain Mexican journalists worked for small independent digital outlets that sometimes only posted on Facebook, Irazoque said, saying their stories delved into local political issues.

Mexico’s National Association of Mayors (Anac) and its National Conference of Governors (Conago) did not respond to requests for comment on the role of state and local governments in the murders of journalists or allegations of ties to criminal groups.

López Obrador frequently lashes out at the press, calling reporters critical of his administration “liars” and devoting a weekly segment of his daily press conference to the “lies of the week.” He condemns the murders, but accuses his opponents of talking about violence to discredit him.

Irazoque says he has no evidence that the president’s verbal attacks have resulted in violence against journalists. López Obrador’s spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.

“What kind of life is this?” said journalist Rodolfo Montes, looking at security footage from inside his home, where the Mechanism, to which he first signed up in 2017, had installed cameras in the parking lot, the street and entrance.

Years before, a cartel put a bullet under the door as a threat and since then he has been on edge. In a corner of his house is a file box full of threats from over a decade. Looking at his phone after a cartel threatened his 24-year-old daughter a few days earlier, he said: “I’m living, but I’m dead, you know?”

(Additional reporting by Pepe Cortés in Oaxaca. Editing in Spanish by Adriana Barrera)