At 87 years old, the Cuban Francisco Ramírez Rojas began to cry before being given the result of DNA study where he ratified what his grandfather had repeated so many times: that they, despite everything that was said, were descendants of indigenous people.

The document proves that he, chief of the community of La Ranchería (eastern Cuba), is one of the few living descendants of the Tainos, pre-Columbian settlers of much of Cuba and the Caribbean. It also confirms that, contrary to what is usually thought, the natives were decimated by the Spanish, but not totally exterminated.

Francis is not alone. The members of 27 families in 23 communities in eastern Cuba present a proportion of Amerindian indigenous genes that is double the Cuban average, according to an unprecedented study presented this Thursday by a multidisciplinary team in Havana.

The new research, five years of field work behind decades of previous investigations, adds to ethnographic, historical and even photographic studies, for the first time on a relevant scale, the scientific certainty of DNA tests.

The study “is a milestone”, says the historian of Baracoa, Alejandro Hartmann, one of the promoters of the research on these communities. It also adds to the work carried out by specialists from regions such as Holguín, where the Chorro de Maíta Museum is located.

The analysis of Francisco, for example, reveals that 37.5% of his genes are of Amerindian origin, compared to 35.5% European, 15.9% African and 11% Asian. In the country as a whole, by contrast, the Amerindian component on average is 8%, compared to 71% for the European.

ONLY ANTECESSORS

One more detail is that all the DNA tests in this study -on 91 people, 74 with conclusive results- refer to female Amerindian ancestors. All male ancestors are European and, to a lesser extent, African.

Specifically, as he explains to efe Cuban geneticist Beatriz Marcheco, from the National Center for Medical Genetics, based on these DNA studies, it can be estimated that all these people analyzed come from “between 900 and 1,000 Amerindian women” who lived in the 16th century.

Hidden in the remote areas that their descendants still inhabit, they survived the “demographic debacle of unimaginable dimensions” that, Marcheco explains, followed the invasion of the Spanish in Cuba. Of male Amerindians there is no trace.

Due to the combination of slavery, the brutality of the conquerors and the new diseases, the Island went from around 112,000 inhabitants at the arrival of Christopher Columbus -according to various estimates- to just between 3,000 and 5,000 five decades later.

“It is not unusual that our own books have for years, even the most recent, addressed the total extermination of the Amerindian component of our population. Indeed, we do not have closed communities, but we do have these people who have preserved those physical characteristics, who have that imprint in their DNA,” says Marcheco.

AMBITIOUS MULTIDISCIPLINARY STUDY

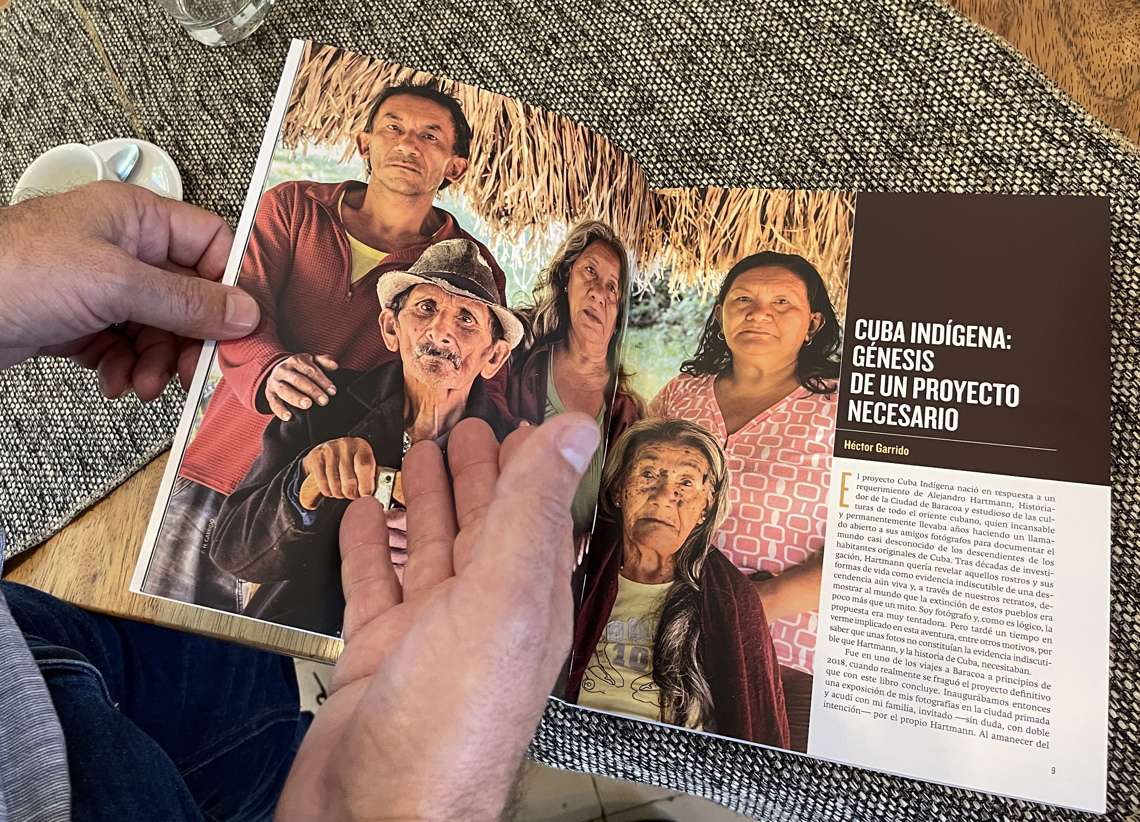

The DNA studies have been the finishing touch to the project, which emerged five years ago as an initiative to portray descendants of the island’s pre-Columbian settlers.

But as the Spanish photographer Héctor Garrido, coordinator of the “Cuba Indígena” project, explains, the initiative evolved towards a “more comprehensive” approach that ended up including historical documentation, portraits, ethnographic studies, anthropological research and, as a “cornerstone”, the genetic analysis.

All these perspectives underline the thesis pointed out by DNA. The physical features show that Amerindian component in the portrayed faces and ethnographic studies collect indigenous traditions such as making casabe (leavened bread cakes), using the coa (agricultural tool), growing wild tobacco and celebrating their own religious rites.

REPERCUSSION

The study, according to its authors, has repercussions in multiple areas. Beginning with the investigated communities -Francisco’s tears are proof of this- and ending with the whole of Cuba. He has also marked them personally, after an intense coexistence with the communities with “big personal implications”, as the project director says.

Garrido emphasizes that these families were “fully aware of being descendants of indigenous people” and felt the “pride of who they are.” However, he adds, they had mixed feelings when they were taught at school “that the indigenous people were extinct.”

The editor of the book on the project, the Cuban Julio Larramendi, is convinced that Cuba will welcome these conclusions with “welcome” and that now is a “good time” to make them known.

“We have that living root, a root that must be fed, given its water, given the opportunity to grow and reproduce, to show which traditions have survived, to show that it is part of our culture,” he points out.

Marcheco delves into this idea: «All this will allow us to reflect, a new look, a reunion with our roots, a reinterpretation of our origins. And that is going to have an influence, not only on Cuban thought, but also on the way in which we accept our culture, our diversity, to the extent that we seek a society that includes all of us.”

Juan Palop/Efe/OnCuba.