October 23, 2022, 1:40 AM

October 23, 2022, 1:40 AM

“If a tiger walked into the room you’re in right now, you’d react, right?” asks neuroscientist Emily Holmes.

“Even if you only watch it for 200 milliseconds, you’d probably jump.”

Now imagine that at some point in your life a tiger actually came into the room you were in and attacked you.

And that image you saw is not true but an intrusive memory.

Replace the tiger with an accident, a violent encounter, a difficult birth… any situation where you or your world could be in danger, affecting you deeply.

Those kinds of experiences can leave you suffering from flashbacks or re-experiencing a traumatic event, “brief moments that come back to mind over and over and over again, as if you were seeing it all over again.”

“They take you back to time and place in a fraction of a second.”

Images like these have been the focus of Holmes’s investigation for much of his career.

They are fascinating because are so fleeting, yet so emotionally powerfulby the associations they evoke”.

And it is that, he explains, although the mental images are not real, we react in the same way as if they were.

“That is one of the brilliant revelations of neuroscience.

“Mental images have been discussed for decades and when we were able to examine the brain we learned that having the image of the tiger in your mind, even though the tiger is not there, is like having an actual experience of visual perception: the same areas light up.

“As far as the brain is concerned, a mental image is just as real as a real one.. And if we see something, even briefly, of course we have to react”, he tells the BBC program “Life Scientific”.

A picture is worth more…

In a landmark experiment in 2005, Holmes, a psychology professor at Uppsala University in Sweden, showed that images are more powerful than words in shaping how we think and feel.

This fundamental insight led her to develop a highly innovative image-based cognitive therapy and digital treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. with the video game Tetris.

“But I must say that there were a very, very large number of laboratory experiments before we got to what we’re doing today.

The treatment “stemmed from a deep interest in finding treatments that may one day be simple.”

And of his deep love for cognitive psychology and psychological experiments.

“Some of the beautiful and delightful work of the last few decades, particularly the 1970s, centers on the idea that our minds are limited in capacity: we cannot do two things of the same type at the same time“.

He realized that this, which seems like a disadvantage, in certain cases could work in our favor.

“It means you can’t hold an image in your mind, like the trauma image, and do something else that also requires you to have an image in your mind.”

Holmes and his team began to explore the idea and noticed that when doing two visual tasks at the same time, the second one caused the images of the first one to become blurry.

“If what we wanted was to dampen the force, so to speak, of the trauma image, we could use the concurrent visual spatial task to do that.”

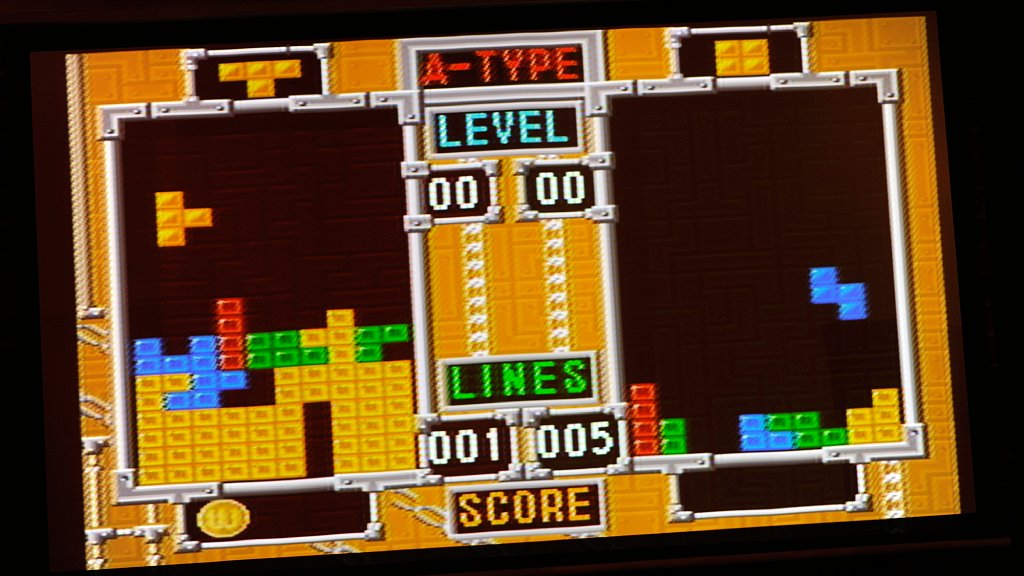

But why precisely with Tetrisan old video game where different shaped and colored blocks float around the screen and you have to fit them into place?

“This was in the late 2000s and at one of the weekly meetings, which our students go to, one graduate said, ‘there are all these free games on phones these days that are like what we’re using on the lab, but much more fun’.

“One of them was Tetris, so we tried it out and it worked wonderfully.”

Testing

The ability to give a wearable device to those who had experienced a traumatic event meant that the treatment could be tested in real life much sooner than normal.

“It’s a shame to see someone after decades of untreated trauma and my idea was always that we could do something sooner that wouldn’t hurt.“.

Despite everything, the first skeptic was herself. She didn’t think she would work. The ideal was, of course, to test the hypothesis in the real world.

They knew that most people who had a traumatic accident arrived at the hospital by ambulance half an hour later.

“We had never done a study with that time gap, but when we first did the intervention we designed, people who played Tetris had significantly less intrusive memories of the trauma one week later than those who didn’t.

“However, even when I got those first data I was hesitant, so the first thing we did was set up a new experiment with even tighter control conditions.”

This time, it was in the lab and with volunteers, who were put through a procedure that included watching traumatic movies, being asked to briefly recall the disturbing images, then playing Tetris, and then given a diary to record. intrusive memories as they went about their normal lives.

“What we found was that, compared to doing nothing, Our intervention significantly reduced the number of flashbacks“.

But they also found that just asking them to remember difficult moments or just playing Tetris did not have the same effect: the video game was part of the treatment, not the treatment itself.

memory degradation

What happened was that the visual memories stopped being so vivid and degraded so much that they mixed with other memories so that they stopped popping up all the time.

“That intrusiveness is problematic because the horrible of flashbacks it is not only that they are traumatic, but that they appear when we least expect it, interrupting our lives. So what we try to do is turn them into normal memories.”

Many more laboratory experiments later, the perfected treatment was put into practice in an Oxford hospital, where the wait for accident patients tended to be around four hours, and the incidence of post-traumatic stress was 23%.

“In that waiting period, patients were given the option to participate in the study and, if they wanted, we used an identical protocol to the one in the lab, which is something I’m very proud of because I really wanted to see if we could adapt the findings of the basic neuroscientific thinking to the clinic.

“The patient didn’t have to talk about what happened in detail, just briefly remember two or three critical moments, and then play Tetris while waiting.”

Incredibly, something as simple as that again worked.

Likewise with mothers recovering after traumatic births.

The hope of Holmes and his team is that while people are waiting to be treated to repair the physical trauma, the mental can also be alleviated.

The neuroscientist continues to work with all kinds of people suffering from different types of trauma, such as intensive care unit staff and refugees.

His dream is to develop psychological treatments for mental health problems that can be made available to everyone..

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC World. Download the new version of our app and activate it so you don’t miss out on our best content.