A few years ago a Spanish woman told me that she saw certain links between the precariousness and political turbidity that exist in Cuba with the stage of the civil war and the Franco regime, saving the distances, of course. I remember jokingly asking him, do you think there will be an uncovering later? And we end up making jokes in which we mention Stella Reynolds, a hilarious character in the series the one that is cominga forgotten star uncover Spanish.

Over time I have discovered great authors who portrayed the Spanish Civil War from various angles, approaches and styles, before, during and after. The theme touches me very closely, because my great-grandfather came from Galicia to Cuba fleeing that war. In any case, it is more a matter of getting to know the prose of these great authors who marked the history of literature in our language and who, coincidentally, shared a time and therefore a theme.

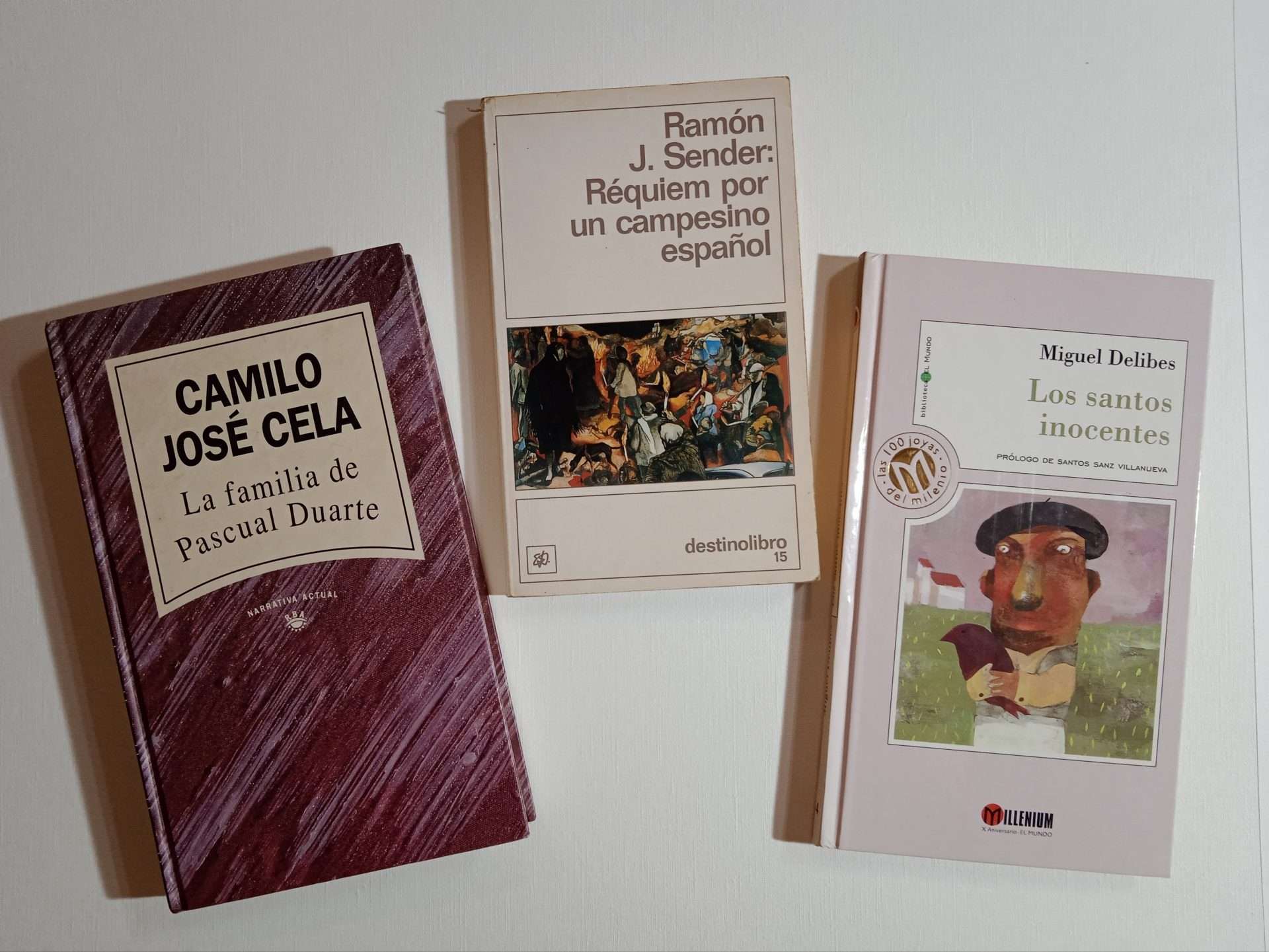

not so long ago I told them of Anya novel by Carmen Laforet, who shared correspondence with Ramón J. Sender, one of the authors I recommend today, and from the same generation as Camilo José Cela and Miguel Delibes, writers all of whom I greatly admire and therefore enthusiastically recommend.

Let’s go, then, to see what these tremendous authors bring us:

Pascual Duarte’s family, by Camilo Jose Cela

The Nobel Prize winner for Literature offers us a story as an exercise in memory, made by the protagonist Pascual Duarte from prison, in which he portrays the precariousness, brutality and spiritual drought that preceded the Spanish Civil War, and does so with a language full of country jargon and careful style.

It is a short, intense and direct novel like a bullet, which seeks to bring the reader closer to those rural spaces where there were no resources, no compassion, no hope of improvement, much less health. It demonstrates the radius of action that marginality has, suffers and reproduces: “(…) It took me a while to find out that tranquility is like a blessing from heaven, like the most precious blessing that the poor and the frightened are given to expect…”teaches the protagonist a lesson, albeit late.

In times of crisis and extreme poverty, vices, criminality, MADNESS increase; the history of the world has shown it. This novel is set in the second decade of the 20th century, and has jumps to the time in which the protagonist was imprisoned until the mid-1930s. It uses letters, plus Pascual’s writings and the notes of the transcriber who tried all his manuscript to put together the complete novel.

The history of this family is the history of any Spanish country family of those years, which taken to the extreme, and who knows, fiction will never be bigger, broader and more unlikely than reality. This novel is quite believable, and almost seems to have a metal plate. based on real events. My great-grandfather, who came fleeing from all that when he was fifteen years old and when Cuba was a country of opportunities, he told me things that he lived in Panton de Lugo, Galicia, where he was from. At times I remembered him sitting in his chair on the porch of my great-aunt who took care of him, with his strong Spanish accent that he never lost in his more than eight decades living in Cuba, telling me about his childhood marked by the rudeness of that stage. . He, like that man Pascual Duarte met during his stay in Madrid, was one of those who was able to escape to Havana and change from madness.

The novel is considered the initiator of Tremendism, which, hey! Look how tremendous Pascual’s life is, and Cela’s prose! It has a style that is pure Spanish idiosyncrasy, it plays with phrases, word order, popular wisdom, and with a level of synthesis and beauty that manages to narrate the cruelest in an attractive way. The impressionism of his prose makes you feel smells and colors, his descriptions are plastic and the dialogues very precise.

The life of Pascual Duarte’s family makes us reflect on the lack of affection and its consequences on mental health; the value of freedom; about the value of family support and understanding; about man as the fruit of his context; about the virtues of tranquility, that which seems so foreign to the condition of being poor; about the importance of patience, communication and venting when it comes to overcoming traumas, as opposed to impulses, silence and unhealthy discretion; about the toxicity and violence that surround the masculine condition and the suffering and submission that prevailed in the feminine condition —according to social and religious precepts.

Pascual is regressing, his values begin to be distorted and he loses the north to become a receptacle of hatred. We know that he ends up in jail, and yet the ending is unpredictable. Brutal scenes of violence.

Coincidentally, this novel, which together with Don Quixote of Cervantes and Any by Carmen Laforet, are among the three most translated into other languages in Spanish literature, they present an image of Spaniards that is quite flirty with mental disorders, mainly in men —what a coincidence!

Here is an unmissable and fundamental classic for those who like good literature.

Requiem for a spanish villagerby Ramón J. Sender

It is a story about the horrors of the Spanish civil war. In a small Aragonese town, Monsén Millán, the town priest, before officiating the requiem mass for the soul of Paco, for whom he was very fond, recalls details of the deceased’s life, since he was always in his life, from the birth, baptism, upbringing, wedding and death. Paco’s enemies want to pay for his mass, but why? Why is there so much guilt around the deceased?

The story manages to give an idea, in a few pages, of the horror of the war, of how it transformed the lives of the peasants, sowed division, and also sheds light on part of the causes of that war. All part of the tragedy; the reader knows that Paco is dead from the beginning, and that his death was scandalous. Hence, everything is more about how Paco died, and who he was.

Written in a sober and simple way, it also uses the jargon of the Spanish peasantry and its superstitions to create realistic dialogue. It does not fall into pamphleteering, although history lends itself to it.

Paco is the true protagonist, despite the fact that the narration is guided by the priest Millán from the third person. The flashbacks What the priest does while waiting to start mass make up the round story that, on the other hand, rolls like a movie in the mind of the reader. The death scene is very filmy and melodramatic. There are quite picturesque characters such as Jerónima and the shoemaker, the others, well, from the heap and go through shots, mainly the rich.

It is a little book that can be read in one sitting and keeps alive the memory of macabre events that should not be repeated.

I liked it, and it has left me thinking about the uselessness of religion for practical things, the importance of discretion when thinking against the current in environments hostile to “what is different”, and how much lies and lies can save and achieve. mischief in times of war.

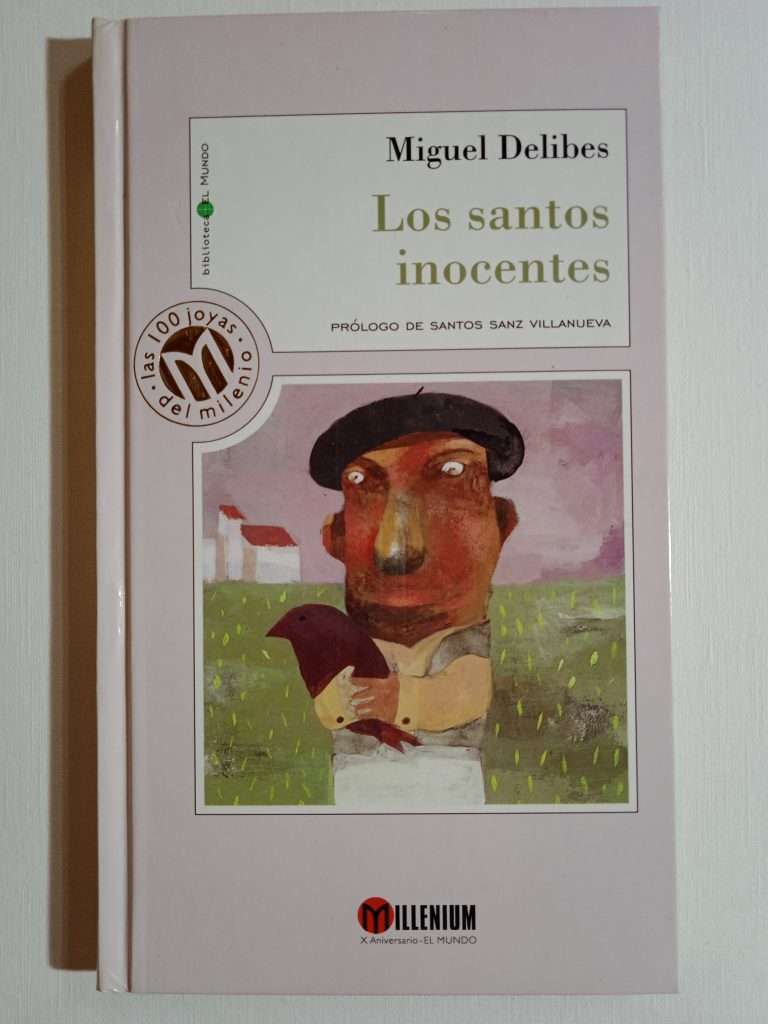

the holy innocentsby Miguel Delibes

It is a short novel, considered one of the best of the 20th century in the Spanish language.

It portrays the rural life of Franco’s Spain, and how even in those environments people lived in a backward, almost feudal way. He uses half-caricature-like characters, models of good and bad, or rather exploiter and exploited, who represent the two main social classes of that time and context: the servile poor with no choice but to serve, and the rich despots, conceited and spoiled.

The novel is a prose denunciation against inequality, abuse, social injustice, as well as the objectification of workers, reduced to machines for making things. There are moments of such organic cruelty, and narrated with such little sentimentality, that they leave you speechless, like when Paco el Bajo broke his leg and Iván el Señorito thinks about his stupid hunt more than about the health of his employee. The character of Zacarías caused me a little pity, because, unfortunately, people with mental challenges are underestimated, and their emotions are not taken into account. However, he is the “alienated” person, the only one who takes revenge against the despot who has hurt him on purpose.

Not only the novel, which is read in nothing, contains the story itself, its ending is like a suspense, but the very rhythm of the story and everything it denounces makes one know where everything is going to end. Which leaves us wondering about the continuity of these abuses of power, these injustices, and how the poorest continue to be the greatest accumulators of injustices and humiliations. I loved the style of his narration; the omission of the scripts when capturing the dialogues, the rhythm, the economy of language, the aesthetics in general. Zacarías, as a character, helps us to notice the importance of respecting everyone’s feelings, above their economic and mental conditions. Another detail that I liked was the lack of partisanship, there is nothing pamphleteering; It is an exhibition of facts and people, a portrait of rural Spain in those years.

These three “Librazos” —also brief— marked the history of literature in Spanish. It is important that we read about what others lived in another time, and thus avoid repeating mistakes, although history has a bad habit of repeating itself, and ignorance always tends to invoke injustice. Let’s save ourselves then with reading.