The pandemic that leaves us has placed health and its relevance for humanity in a position that perhaps it never had before, with everyone understanding that the patient must be at the center. This generates an immediate political effect: pressure to increase health budgets. This was confirmed by a recent study by the OECD, for a group of 17 member countries, where health spending increased by an average of 6% in 2021 alone. This is especially worrying in the face of the challenge that global inflation imposes on us.

In this context, it is worth remembering that numerous investigations worldwide have shown significant inefficiencies in health spending, so simply increasing it is not the solution. As a way of comparing the different realities between countries, these studies usually use indicators such as life expectancy and infant mortality rates as production variables. Back in 2004, a global analysis by William Greene revealed an average efficiency score of 0.80, meaning that, on average, countries could increase health outcomes by 20% without using additional resources. Subsequent studies have confirmed this trend.

A few months ago, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) published a study on patterns and driving factors of the efficiency of health spending, where it highlighted that the main levels of inefficiency occur in countries with a lower level of development, compared to economies advanced. The good news, yes, is that it was also shown that for the vast majority of the countries analyzed there had been gains in efficiencies in health spending, for the period 2007-2017.

Among the factors highlighted by the IMF as positive for spending efficiency are, first of all, and this is not new, immunization campaigns. Likewise, the integrated care strategy, in which several health problems are addressed simultaneously, contributes positively to efficiency. Similarly, other studies highlighted by the IMF point to inefficiencies inherent in systems centered on the hospital, while those whose center of gravity is primary care tend to reverse this phenomenon.

On the other hand, the IMF itself highlights other factors that are not only specific to the health sector, but that would also affect the levels of inefficiencies.

In this sense, income inequality in the population and/or low educational levels, linked to the so-called “Social Determinants of Health”, can inhibit the effective conversion of financial resources allocated to the health sector, in a longer life expectancy. . In the case of countries with lower levels of development, where hygiene conditions are often inadequate and nutritional security is still not achieved, investment in the health system can continue to expand, without observing positive results in terms of efficiency. As a counterpoint, populations with higher levels of education tend to have healthier lifestyles, with which they avoid, in an important way, having to recharge the health system. In the same sense, more educated populations use preventive health more frequently, reducing the prevalence of diseases.

On the other hand, the harmful effects of poor governance and corruption on the efficiency of health service delivery, which in turn hampers their growth and development, are widely documented. In the health sector, in particular, it is estimated that 455,000 million dollars of health expenses are lost worldwide due to corruption.

Finally, the IMF highlights that the coverage of the population with essential health care, consisting of a minimum and basic package that includes prevention, treatment and rehabilitation services that is progressively expanded, can be an efficient way to deal with the most important causes of illnesses and deaths.

What the IMF study does not mention, as a measure to be implemented in the various countries, is the enormous relevance of the economic evaluation of health technologies (known by the acronym ETS or ETESA, and which is part of Health Economics) , as a way to improve efficiency in the use of health resources. There are already several decades of HTA development, with more or less robust institutions in various countries. ETS should inform policy makers about the value that a given resource allocation (health intervention) confers on society, usually conceptualized as utility maximization or quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) .

However, efficiency should not be the only thing pursued through decisions on the allocation of health resources, but also equity, social preferences, among other factors, that make these decisions acceptable to the population and sustainable in the future. long term, both financially and politically. Notwithstanding this, in times of global uncertainty, it is increasingly necessary not only to spend more on health, but better, in a collaborative exercise of the different actors in the system. For this, it is necessary to constantly invest in improving the institutional framework and training of experts capable of making sophisticated and complex decisions, always listening to civil society, which, as far as possible, are followed by the political systems. This, for the benefit of the population, but above all, to the patients.

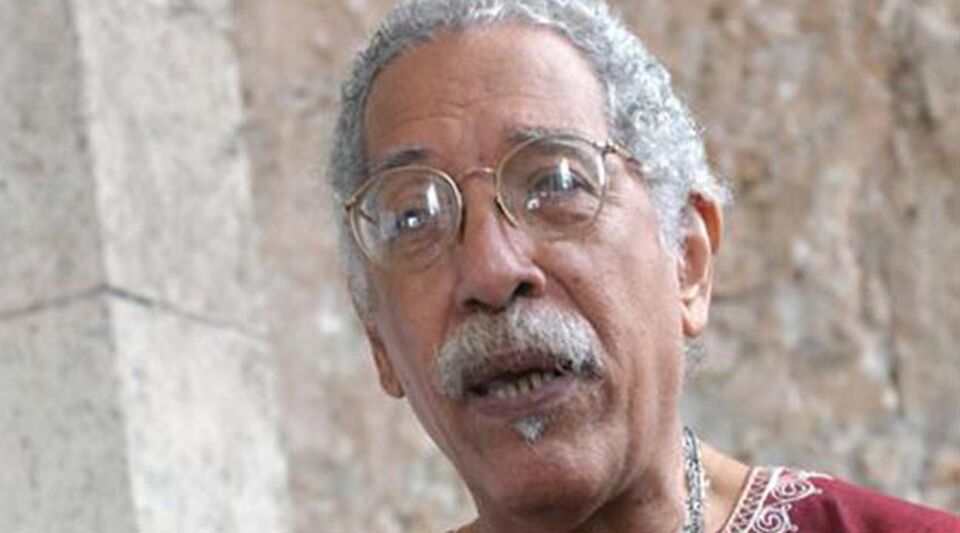

*The author is an expert in public health policies, Director of the Chilean Association of Health Law, and has been an academic at various Chilean universities on issues related to health systems.