It is an innovation that was developed in China. They published the results in the scientific journal Matter. How the wearable device works and in which situations it would be most useful.

A team of scientists in China has created a mask that can detect the most common respiratory viruses, such as the flu and coronavirus, in the form of droplets or aerosols. It is a highly sensitive mask that can alert users via their mobile devices within 10 minutes if pathogens are present in the surrounding air.

During the pandemic, different masks have become essential to reduce transmission and save lives, along with physical distancing, reducing gatherings in closed and crowded environments, permanent and cross-ventilation of interior spaces, regular handwashing and cover your sneeze or cough with a tissue or the inside of your elbow.

Chinese researchers sought to add value to the use of the chinstrap. So, they created a product that not only protects against pathogens but also alerts them to their presence. “Previous research has shown that the use of masks can reduce the risk of contagion and contracting the disease. That’s why we wanted to create a mask that would detect the presence of viruses in the air and alert the wearer,” explained Yin Fang, one of the study’s authors and a materials science researcher at Shanghai Tongji University. The research was published in the Cell group’s journal Matter.

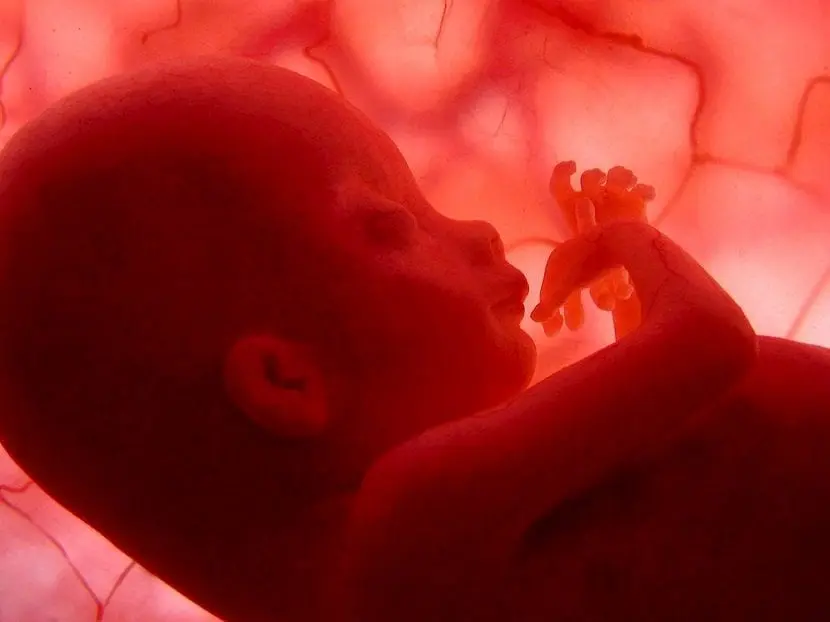

How the mask that detects COVID-19 and the flu virus can be used Down: They created in China the portable bioelectronic mask that may be able to detect if there are viruses in the air of the place Credit: Matter / Wang

The respiratory pathogens that cause COVID-19 and H1N1 flu are spread through droplets and aerosols released by infected people when they talk, cough, and sneeze. These virus-containing molecules, especially tiny aerosols, can remain suspended in the air for a long time.

Fang and his colleagues tested the face mask in a closed chamber. They sprayed viral surface protein containing fluid and trace-level aerosols onto the mask. The sensor responded to as little as 0.3 microliters of fluid containing viral proteins, between 70 and 560 times less than the volume of fluid produced by a sneeze and much less than that produced by coughing or speaking, Fang said.

The team designed a small sensor with aptamers, which are a type of synthetic molecule that can identify unique pathogen proteins such as antibodies. In their proof-of-concept design, the team modified the multichannel sensor with three types of aptamers, which can simultaneously recognize the surface proteins of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, and the H5N1 and H1N1 influenza viruses.

Once the aptamers bind to the target proteins in the air, the attached ion-activated transistor will amplify the signal and alert users through their phones. An ion-activated transistor is a new type of highly sensitive device, so the mask can detect even minute levels of airborne pathogens within 10 minutes.

“Our mask would work very well in spaces with poor ventilation, such as elevators or closed rooms, where the risk of getting infected is high,” Fang said. In the future, if a new respiratory virus emerges, they will be able to easily update the sensor design to detect the new pathogens, he added.

The team hopes to reduce detection time and increase sensor sensitivity by optimizing the design of the polymers and transistors. They are also working on wearable devices for a number of diseases, including cancer and cardiovascular disease.

“Currently, doctors rely heavily on their experience to diagnose and treat illnesses. But with the richer data collected by wearable devices, disease diagnosis and treatment can be more accurate.”

The work to create the mask was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Science and Technology Commission of the Shanghai Municipality, the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project Shanghai and the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities.