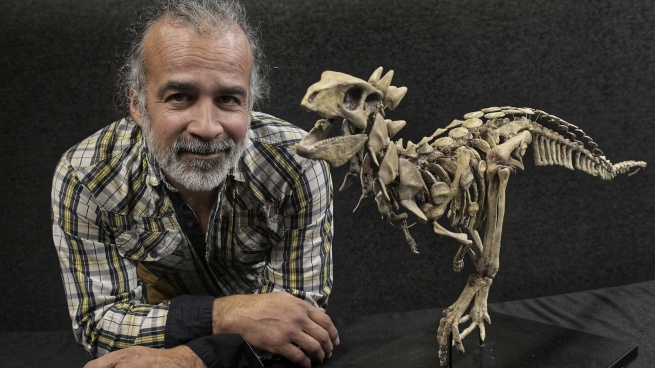

Currently an independent researcher at Conicet and director of the Paleontology Area at the Azara Foundation, Apesteguía received a doctorate in Natural Sciences from the University of La Plata and has to his credit the discovery of more than 30 species of prehistoric animals in our country, 62 publications ( six of them in the journal Nature).

Among his feats, the most recent were the presentation of Jakapil kaniukura, the first armored dinosaur found in the Southern Hemisphere, and the alphabet of Argentine dinosaurs to spread in schools.

But beyond his recognized achievements, Apesteguía is still the boy who dreamed of carrying out expeditions. Each of the answers that he gave in an interview with Télam-Confiar should be read with a laugh in the background, with the joy and enthusiasm of someone who fulfilled his mission, but without stopping “playing”.

In this interview he reviews his history, from when he drew dinosaurs on his school bench to his more than 30 discovered species.

As a boy, he already dreamed of being a paleontologist. How were those fantasies and the transition to your reality?

I started drawing prehistoric animals on the benches at school, but later I wanted to know about them and compiled data, although my knowledge was messy. Until in sixth grade, my teacher Noris asked me to teach a class with her about prehistory. She posed a challenge to me, she had never thought before to order the information that she had to transmit it.

A year later, an article came out in Billiken Magazine that blew my wig off. It said: “Living dinosaur found in Africa.” The short text mentioned the researchers and the source of the note: NYT, by The New York Times. To find out more, I went to the Lincoln Library in CABA, which was connected to the US Embassy. I told them that I wanted to look for an article and since I didn’t know which newspaper it was in, they gave me all of them, a giant pile in English, a language that I handled very crudely. Then we go to microfilm. I spent a month until I found the news, which I transcribed by hand. I wrote a letter to the authors, from the University of Chicago, they responded and I even became a member of the International Society of Cryptozoology, but I only lasted a month because I was 13 years old and I did not have the means for a dollar fee.

I continued with the idea of traveling to the Congo when I could to look for the “living dinosaur”. Two years later I said to myself, “What can I do to prepare? So I set out to learn a native language. I told a high school teacher of mine, Susana Andrés, who got me an interview with the president of the Argentine Association of African Studies. I remember that he was an older man who told me then: “I don’t think there is anyone who speaks Lingala in Argentina, but let me find out, I’ll call you in a month”. Fifteen days passed when she contacted me to tell me that he had made an appointment for me with a Congolese nun who was doing an internship in a restaurant in Luján. I went there with a piece of paper on which I wrote down a list of words. A week later, she translated everything for me, although I confess that Lingala was impossible for me.

When I was 16, I became a boyfriend and when we broke up, two and a half years later, in addition to being sad, I noticed that I had a lot of free time left. So, when I was 18, I went to the Museum of Natural Sciences, I applied to paleontology and Dr. José Bonaparte attended me there. I told him that he wanted to help. He, big, imposing in his white apron, replied: “Come in a month, kid, now I don’t have time.” I showed up and he gave me the first task: he brought a can of bent nails, a hammer and told me “straighten them all”. Later I moved on to work more related to paleontology and that same year, precisely in the summer of 1989, I went on a campaign to Patagonia for the first time. But that’s how I started, straightening nails.

Was the nickname ‘Ninja’ born at work?

Yes, but like a load, it’s not that they called me that seriously. Since I am the son of a lawyer and a shop assistant, I hardly had any tools at home. So, when I arrived at the museum, I had a universe of them: welding machines, grinders, everything was necessary to assemble the skeletons of the dinosaurs, the platforms, break a wall. When I finished my work and had a little free time, I would shape an iron to make a sword for myself. And I cut little pieces of tin to turn them into little ninja stars. With all this, the nickname was quickly put.

How was the experience of working with José Bonaparte, the “master of the dinosaurs”?

Bonaparte always gave you the opportunity, but he was a difficult guy, because he was always right and unapologetic. He was of very humble origin and in his native Mercedes, he had worked as a carpenter. I remember an anecdote in which he skillfully sawed wood to make a platform. At one point he got stuck with the saw and the blade, which went flying, touched the back of my hand. I started to bleed, not as much, but he was bleeding. I, who already knew him, stood firm without blinking, holding the wood. He replaced the saw and went on with his business. When he finished, he said to me, “So you had red blood too?” In fact, I wrote about working on it in a free downloadable book.

How did paleontology and its conditions change from when it began to today?

Paleontology is a science that changes little over the years. Even the field photos of colleagues from other countries like the United States are practically identical to ours. That makes it special and it has its magic, because we work the same way we worked in the 19th century. Of course now we have better vehicles, like a late-model truck owned by the Azara Foundation, but I started with my ’58 model car, with which I went to Patagonia even though it broke 10,000 times. At the beginning we put everything from our pockets because otherwise the expedition would not take place.

Currently, a large part of those who graduate in paleontology if they do not have all the guaranteed means, if there is no institutional vehicle, if they have to put up money themselves, they do not campaign. And that when I started was unthinkable. The first thing was to go. How? We saw it. If money had to be put, it was put, even if we didn’t have it. In one of my first campaigns I went by bus, it was risky and I wouldn’t do it today, but there was another spirit as well.

He recently presented an alphabet of Argentine dinosaurs. How did that idea come about?

Argentina, due to its large number of discovered dinosaurs, has become the only country in the world with the possibility of giving each of them a letter of the alphabet. I realized this when I saw an alphabet made in the United States with species from all over the world, but not a single one from our country. Then I began to replace each letter with an Argentine dinosaur and I saw that we had almost all of them. We were only missing the “J” and the “Y”, but for the latter we could put a Cretaceous bird and explain that birds are also dinosaurs. There was only one letter left.

So when it was our turn to name the last discovered dinosaur, we discussed the name with my student Facundo Riguetti and I told him “Facu, whatever you want, but it has to be with J” “Why?”, he asked me. I told him it was the missing letter of the alphabet. “So?”, he answered me. I excitedly explained that we could distribute the alphabet to every school in the country. It was Facundo who named him Jakapil kanikura, with the condition that I put on him that he start with J. That’s how his name stayed.

What does paleontology mean to you?

I usually define myself as a “history diver” because I’m not only interested in paleontology but going to what was before. In fact, when I and my partner Cecilia were in France, we were given the chance to visit Roman ruins, but we ended up visiting an oppidium, which are much older ruins.

On that same trip, I wasn’t interested in studying French but learning Occitan, which was the language spoken before the Franks arrived. And one of my three dogs is a pile dog, which is the Native American canine. I am driven by origins, the ancient history of things. So paleontology is just one more chapter in this dive of history.

What is the achievement you remember most fondly?

The achievement I remember most fondly has nothing to do with paleontology: it’s being a dad. I went when I was 41 years old, when I already had a large part of my career on the way. Then I was able to dedicate myself fully to fatherhood. Regarding the achievements in paleontology, the most important is the discovery of the paleontological area of La Buitrera, my main place of work in Río Negro.

It was defined by foreign researchers as the “South American Gobi” because the Gobi is an icon of world paleontology. It is important to point out that in La Buitrera, unlike other large sites that deal with the great dinosaurs of the same era (that of the giants), small animals are preserved: lizards, snakes, crocodiles.

What advice would you give to those who want to study paleontology?

First, that paleontology is very large and encompasses much more than dinosaurs and vertebrates. It is all life carried into the past, even fossil unicellular beings, where evolution and natural selection were the same. You have to allow yourself to delve into other species, because paleontology requires the effort that there are people studying them.

Second, that to graduate in paleontology you have to study many subjects that may seem useless to you, such as “mathematical analysis” or “plants.” But students should not fall for the subjects that they do not like at the moment, since most of them have a reason for being: since paleontology is so broad and studies all the manifestations of life in the past, future professionals are going to need various tools to understand it.