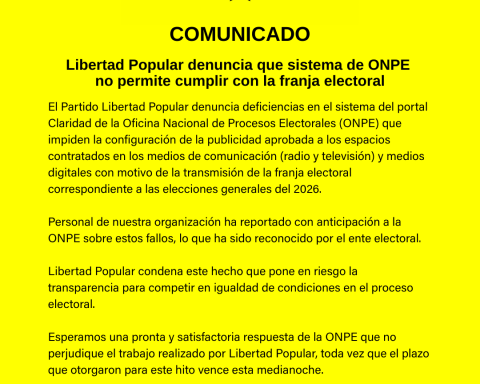

From Saudi Arabia to West Texas, Drillers are pumping more oil to cash in on the scorching price rally. However, the region that is home to a fifth of the world’s crude oil reserves is missing the party.

(Read: Health concern: America, epicenter of monkeypox).

Throughout Latin America, the advantages of price of US$100 per barrel they have been tempered by nationalist policies that tightened government control of the energy industry and marginalized foreign investors who had helped boost production. Production from Brazil and Guyana is increasing, but throughout the region, supply has fallen so far that it now barely meets local demand.

Mexico and Argentina they import more crude oil and natural gas than they export, a change from the last oil boom a decade ago. Reliance on expensive fuel imports is putting the leaders of Latin America’s oil-producing countries squarely in the political crosshairs.

The violent reaction of motorists after the price increase is leaving the Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro lagging behind his main rival before the October elections. Ecuador’s president was narrowly ousted after protests over fuel prices and inflation.

For its part, Mexico spends billions to subsidize gasoline. All this means that the world does not count on Latin America to increase oil and natural gas production as the Russian invasion of Ukraine reduces world supply. While US and Middle Eastern producers are increasing supply, it is not enough to stop runaway price increases that threaten to trigger fuel rationing and push economies into recession.

It’s a stark contrast to how early booms played out. commodities in Latin America. In the 2000s, leaders like Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez used windfall cash from oil and gas to bolster their popularity at home and expand their regional influence. But those gargantuan revenues were only made possible by foreign investments that boosted production.

When Chavéz nationalized the oil industry, the big projects were mismanaged and the money dried up. “The oil industries have fallen victim to the resource nationalism that prevailed during the super cyclesaid Francisco Monaldi, professor of energy economics at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy and an expert on Latin America. “Now they don’t have the ability to do what Chavez did in 2003 and 2004, to generate massive spending “.

(Keep reading: How were the 4 unique visits of Queen Elizabeth II to Latin America).

Of course, if crude prices hadn’t soared this year, trade balances would be even worse for Latin America’s state-owned oil exporters. Brazil’s Petróleo Brasiliero SA, Ecuador’s Ecopetrol SA, and even Petróleos Mexicanos, Mexico’s heavily indebted oil company, are reporting stellar profits and paying solid dividends.

But it takes time for higher tax revenues from crude exports to reach government coffers, and only a prolonged supercycle would eventually bring relief to tension in the region. The broader economic benefits of the oil rally have not been enough to derail an anti-system wave throughout Latin America.

Latin America

istock

Colombia recently elected a leftist to the presidency who plans to ban fracking. In Brazil, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who presided over an economic expansion during his first Administration thanks in large part to commodity, sounds like the favorite to replace Bolsonaro in the next elections. In Monaldi’s view, oil fields in Latin America would be pumping 20 million barrels per day, more than double current levels, if producers had all the benefits Texas drillers enjoy, such as easy access to capital. , low taxes and light regulation.

(Read: The agreement between the EU and Mercosur “remains firm”).

Instead, interventionist policies, such as seizing stakes in oil fields from foreign partners, raising taxes and not exploring areas conducive to drilling, are hurting production. small gains

This year’s top winner in the region is offshore drilling newcomer: Guiana.

However, the country will not see further increases until 2023, when production arrives. floating Exxon Mobil Corp. Venezuelan production recovered following a relaxation of US sanctions in 2021, but it is not clear if it will be able to expand or even maintain current levels, its production remains a shadow of what it was just five years ago.

The gains for Brazil, which has significant offshore resources yet to be exploited, have been modest. Even the increased production from Argentina at the highest level in a decade it is unlikely to bring any relief to the markets, as the country is only a medium producer. Infrastructure restrictions and internal price controls limit how quickly it can expand despite world-class shale deposits.

In total, the International Energy Agency it only expects 400,000 barrels per day this year from Latin America, a third of the expected growth in the US The region’s main production success story this century has been Brazil, but even there production would double current levels if the first Lula would not have stopped development for half a decade to rewrite oil legislation, Monaldi and other analysts said.

If Lula wins as expected, one of the main concerns is that the government will delay the development of large fields to increase the state’s participation, said Andre Fagundes, who covers Brazil for energy consultancy Welligence. Petrobras is currently preparing to drill in a little-explored offshore region near the equatorial margin.

If Brazil makes major new discoveries, such as the recent successes in Guyana and Suriname, the Lula government could delay development to raise taxes, Fagundes said. “This could be a subject of review for future licensing rounds,” he said.

BLOOMBERG