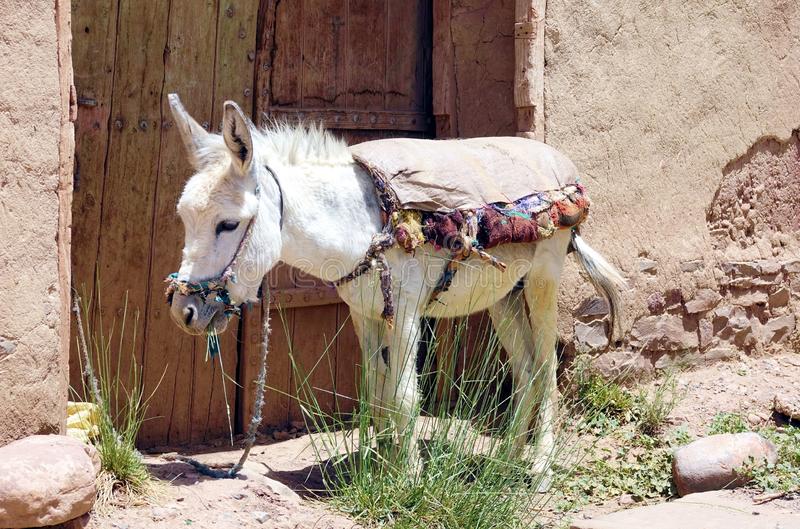

Domestic donkeys have been important to humans for centuries, even today in many countries, however their genetic history is little known and suggests that this animal has been with us for more than 7,000 years and was domesticated in Africa.

Source: EFE

This is the conclusion of a study published today by Science by an international team led by the Center for Anthropology and Genomics in Toulouse (France).

The team performed a comprehensive genomic analysis of modern and ancient donkeys (Equus asinus) to trace the origins, spread, and management practices underlying the domestication of this important pack animal over thousands of years.

Experts believe that understanding the largely ignored genetic history of the donkey is not only important to assess its contribution to human history, but could improve local management of the animal in the future.

Despite its importance to ancient pastoral societies in Africa, Europe, and Asia, little is known about its long history with humans, particularly regarding its origin, domestication, and the impact of human management on its genome.

The team headed by Evelyn Todd, from the aforementioned French center, evaluated 238 genomes of modern and ancient donkeys to discover new clues about their history of domestication.

The researchers found strong phylogeographic evidence supporting the existence of a single domestication event in East Africa more than 7,000 years ago, around 5000 BC.

This was followed by a series of expansions throughout Africa and into Eurasia, where the subpopulations became isolated and differentiated, perhaps due to the aridification of the Sahara.

Over time, gene flows from Europe and the Middle East made their way to donkey populations in West Africa, explains Science.

The analysis also uncovered a new genetic lineage from the Levante region that existed approximately 2,200 years ago and contributed to increased gene flow into Asian donkey populations.

The study also contains information on donkey management, including breeding and ranching, as well as evidence of selection for large size and significant inbreeding in former donkey populations.