The repercussions of the Chile conference in the Dominican Republic exceeded all expectations and fears. In compliance with the Fourth Resolution of the Foreign Ministers, a special OAS commission visited different countries in the area in the following months, in order to render a report on the terrain of the political tensions that were plunging the international situation of the country into a serious crisis. Caribbean. In the meantime, the conflicts between Venezuela and the Dominican Republic became much more intense and the same happened with respect to the confrontation with the Revolutionary Government of Cuba.

In mid-January 1960, Colonel Abbes García’s SIM agents discovered a new conspiracy. This time, the networks extended to the most recondite corners of Dominican society. Upper-class youth were equally engaged with middle-class professionals and students and members of the proletariat.

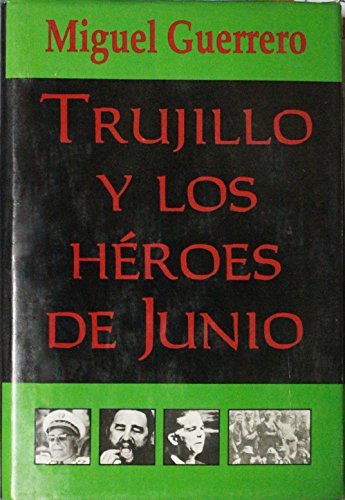

The list of those involved that Abbes García drew up startled Trujillo. Direct descendants of his close and trusted circle appeared in it. Their names worried Trujillo as much as their numbers. If the SIM reports were correct, and for the most part they were, it had to be concluded that the foundations of the regime were eroding. The noise of the June battles had ceased to be heard months ago, but it was the spirit of that deed that encouraged the young people who now faced him. They had even taken the date of his immolation as a flag: they called themselves the June 14 Revolutionary Movement, in memory of those heroes.

On June 24, 1960, a year after the landings, Trujillo carried out the worst and costliest of his foreign adventures. With the complicity of a group of Venezuelans opposed to President Betancourt, he planned and financed the execution of an assassination attempt on the Venezuelan leader.

While he was driving in his car to the Military College, on Avenida de los Próceres, in Caracas, where a military parade commemorating Army Day would take place, on the anniversary of the Battle of Carabobo, the conspirators remotely detonated a charge of dynamite deposited in the trunk of an old Oldsmobile parked on the side of the road where the presidential delegation would pass. Betancourt’s car rolled to pieces, killing the head of his military assistants, Colonel Ramón Armas Pérez, in the explosion. The president suffered serious injuries to his hands and face.

The attack was followed by a Venezuelan diplomatic action that culminated, two months later, in August, with a ministerial conference. The Sixth Meeting of Consultation of American Foreign Ministers, held in San José, Costa Rica, approved the imposition of unprecedented diplomatic and economic sanctions against the Dominican government. The move definitively isolated Trujillo and aggravated the internal problems that were gradually but steadily undermining the once-solid foundations of his absolute power.

Cornered by the effects of sanctions, external pressure and resistance in the provinces, the tyrant would astonish the world with one of the most horrendous and unjustified crimes of his three decades of bloody rule. On the evening of November 25, 1960, three months and four days after the sanctions were approved, Colonel Abbes García’s agents stopped the vehicle in which three sisters were traveling and after beating them to death, they threw their bodies and that of their driver for a cliff The murder of the sisters Minerva, Patria and María Teresa Mirabal, while they were returning to their native Salcedo, from Puerto Plata, where they had gone to visit, as usual, their husbands imprisoned since the January raids, filled the community with fear and indignation. Dominican society.

This barbaric crime broke the last weak ties that still united the regime with the representative sectors of society. Internal resistance grew and with it the repression became more drastic. The prisons were filled with young people and at the slightest suspicion they went straight to the torture centers of the forty and the kilometer 9, the first under the orders of Abbes García and the second under the jurisdiction and care of Military Aviation officers. Thousands of Dominicans of all ages and sexes died there from the effects of beatings and the most sophisticated ordeal between June 1959 and the following two years.

On May 30, the Generalissimo was the victim of his own violence. While he was driving, at night, in the sole company of his faithful driver, Captain Zacarías de la Cruz, to his country residence in his native San Cristóbal, located about 20 kilometers east of the capital, his Chevrolet model 1957, was intercepted by a group of conspirators made up of friends and collaborators, who shot him to death. After being kicked, Trujillo’s body was deposited in the trunk of the car of one of his killers and taken to a residence, where hours later he would be found by SIM agents.

The attack unleashed a bloody hunt that culminated days later with the murder of those involved and the imprisonment of their relatives. But it also allowed the start of a transition period that would end seven months later with the installation of a seven-member Council of State headed by President Balaguer, who had already been sworn in as such on August 3, 1960, in a Trujillo’s useless attempt to stop the diplomatic process that would lead to the imposition of sanctions against him.

Formally, the Era of Trujillo was liquidated. However, the deep imprint of his iron fist would remain marked for years in the development of life in the country. After months of instability, which forced Balaguer into exile in March 1962 amid violent street clashes, Dominicans elected their first democratic government on December 20 of that same year. The presidency of Juan Bosch, an anti-Trujillo exile leader with very liberal ideas for a nation marked by obscurantism and political ignorance from three decades of tyranny, only lasted seven months. In the early hours of September 25, 1963, Bosch was overthrown by a right-wing military coup that installed a Triumvirate in his place.

Between late November and December, the de facto government faced strong opposition, including a guerrilla uprising led by the June 14 leadership, the organization formed four years earlier in the wake of the 1959 guerrilla expeditions. The insurrection was quickly decimated. and its main leaders assassinated, among them its commander in chief, Dr. Manuel Aurelio Tavárez Justo (Manolo), widower of Minerva Mirabal, the eldest of the three sisters assassinated by Trujillo’s henchmen in November 1960.

Dominated by corruption, the Triumvirate soon found itself the target of numerous civil and military conspiracies. On Saturday, April 24, 1965, a military movement calling for Bosch’s return to power degenerated into a popular rebellion that provoked a US military intervention. At the beginning of May there were already more than forty thousand US soldiers in the national territory, an intervention to which the OAS later conferred a multilateral character by creating an Inter-American Peace Force (FIP), to which symbolic troops from Brazil, Costa Rica and , Nicaragua and Paraguay.

After bloody fighting, with an estimated balance of several thousand dead, the parties to the conflict reached an agreement that put an end to hostilities. On June 1 of the following year, 1966, elections were held again with the presence of the occupying forces. Balaguer, who had returned from exile, was elected President of the Republic against a Bosch who was barely able to campaign under strong pressure and threats from his enemies in the Army and the radical right.

After several reelections, all of them denounced as fraudulent by his opponents, and a brief interlude of eight years in the opposition, between 1978 and 1986, Balaguer was still President of the Republic in 1996, when this work was published.