You have to carry a few years on top to remember that concise and inviting notice. In the golden age of cinema, we all knew that before the movie we were going to be bored with an advertising campaign. Personally, I remember the picturesque key-li, or Scottish dance that was danced, to the sound of bagpipes, by the carved goblets of Johnny Walker. Or the dazzling navy blue color of Nivea cream. You have to be located in a time when there was no television so the barrage of images in dazzling colors was enveloping and magical.

And at the end of the series, a slide with that “And then, everyone to the Lido Bar…” would come crudely onto the screen. I don’t know if it was coincidence or some marketing genius, but we all knew that after the Lido announcement, the movie was coming. A pleasant association of ideas. That after could be a surubí soup, or a horse steak with egg and, why not, a bread pudding with lots of caramel sauce.

I do not know if that advertising as simple as it is effective is still valid. What is certain and definitive is the corner of Palma and Chile, with the Panteón de los Héroes opposite, is closing its doors and moving elsewhere.

It’s not just the closing of a bar. It is the disappearance of a privileged witness of much of contemporary history.

LOS AGITADOS ’50 – The Lido Bar appeared on the scene on July 26, 1953. Two political events, one distant and the other close, would accompany its birth. That same day, month and year, Fidel Castro led the unsuccessful assault on a Fulgencio Batista army barracks in Santiago de Cuba, a setback that after the 1959 revolution, the Castroists would turn into a heroic triumph.

A year later, on August 15, 1954, Alfredo Stroessner came to power, inaugurating his long 34-year dictatorship, which, however, the regime presented as “democracy without communism.”

Without a doubt, the founders of the Lido Bar took the name from the Lidó de Paris, a cabaret located on the emblematic Champs Elysees avenue that had opened its doors seven years earlier.

Enrique and Elizabeth Schulz, two German immigrants, decided to settle on the ground floor of the then brand-new building located in Palma and Chile and which was on the corner of the Ministry of Finance, the Panteón de los Héroes and an old building that would fall under the pickaxe to give transfer to a foreign bank.

BEFORE THE EDICT – The Lido Bar was always one of the refuges of the Asuncion nightlife since it never closed its doors. It was the ideal place for some post-party yorador or, if you had worked until the wee hours of the morning, to regain your strength with a powerful fish broth, a chicken villeroy, Neapolitan milanesa or any of the delicacies that came out of a kitchen that activated 24 hours a day and “also at night” as the routine night owls used to joke.

But the Lido was not just night. During the day, the technical stopovers to take a snack on the go could be complemented at noon with their battle dishes: horse steak with onion and egg, Neapolitan milanesa, gnocchi with stew and the immortal Provençal fries that no one, in his right mind, he would dare to resist. That, and the ham and cheese, corn and chicken cakes could close a sitting that each one could adjust to the realities of his pocket.

But it was on January 19, 1978 when the Asuncan pax was broken with Police Edict No. 3 that forced all nightclubs to close their doors after 01:00. Although the Lido seemed to enjoy some franchise for a while, the obligatory paralysis finally caught up with it, having to silence its kitchens until the early hours of the morning.

HISTORICAL SCENARIO – It could be said that the Lido Bar was from its beginnings at kilometer zero of events, in addition to the geographical zero symbolized by the Oratory of the Virgin. Professor Luis Alfonso Resck was dragged from his surroundings by the political police of the Estronist regime. There Domingo Laíno debated amid clubbing and kicking, in the days when Ramón Aquino’s acolytes moderated demonstrations and public debate with braided wire and tejuruguay. In 1986, doctors and nurses from the Hospital de Clínicas gathered there demanding salary improvements, receiving in response a fierce repression by the “Investigation hyenas”, the political police who had their lair less than 150 meters from there.

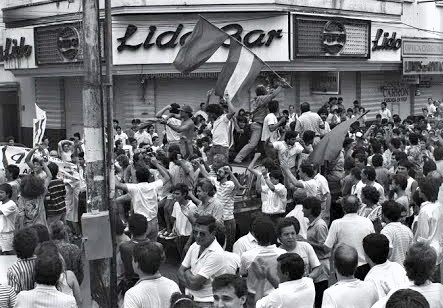

And in that place the citizens would spontaneously meet at the dawn of February 3, 1989, celebrating the fall of the regime and the inauguration of the hope that opened after a long night of oppression.

The Lido was, as in so many other crossroads of contemporary history, a privileged witness. Wherever he goes to take refuge, he will take all that history with him.