The most unusual thing that December 1972 had been the 2-0 victory of the Nicaraguan baseball team over Cuba at the beginning of the month. It was unexpected because Cuba was already Cuba by then and they were not expected to lose to a team like the one Nicaragua had.

In the days that followed, the people of Managua continued to celebrate that victory as the days passed and the dates of Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve approached.

The day before the tragedy, December 22, 1972, the only strange sign was that in Managua there was a reddish sunset that spread its tint over the sky. It looked from Lake Xolotlán to the suburbs at the exit to Masaya and through the Las Mercedes airport.

Related news: Nicaragua expresses its solidarity for the victims of the earthquake in China

That Managua was a small, beautiful city that, although it was not a metropolis, neither had anything to envy to other Central American capitals. It was not necessary to use a vehicle at that time because everything was quite close and very accessible. Banks, churches, government offices, restaurants, cinemas. All of this and more was just a few blocks away on foot.

There was also a lot of activity at night. There was the Versailles Night Club, which normally put on great shows, as well as the Gran Hotel, which was going to offer a farewell ball for the year on December 31, 1972.

Another famous place in old Managua that brought together several diners was La Espuela, a beer hall where professionals converged to chat over glasses and bottles of barley or other cereals fermented in water, malt, and hops. There were also other entertainment options at El Colonial and El Club Social de Managua.

But that year there was no Christmas celebration in Nicaragua. There was nothing to celebrate. Everything was mourning. Ten thousand dead on the eve of the best time of the year.

the first notice

It was an earthquake at about 10 pm on December 22 that gave the first warning to Managuas of what was coming. That first movement alarmed more than one person, but the one that really put the people of the capital on edge was the one at 12:35 in the morning of December 23.

“The inhabitants of Managua could well, without being labeled crazy, have pricked up their ears while waiting for the trumpet. If there really will be a Judgment Day, this was the final essay,” wrote the journalist Horacio Ruiz in one of the chronicles that best describes the tragedy and was published in the newspaper La Prensa on March 1, 1973, with the famous headline “In 30 seconds… Just Hiroshima and Managua.”

“It will be impossible for future generations to imagine what the inhabitants of Managua experienced on December 23, 1972. In war, destruction comes when everyone has fled or taken refuge. It is an expected misfortune. In a hurricane, the early winds blow warningly, relatively gently. In large fires they can flee. In an earthquake like the one of December 23, 1972 in Managua, all of its 400,000 inhabitants were suddenly thrown into a pit of local anguish. To the fear of the moment was added the fear of the future. In seconds, everything had become nothing”, Ruiz recounts in his chronicle entitled Final Judgment Rehearsal.

Román Gutiérrez is 76 years old today and he still remembers that that night he was waiting for his wife who was late from work. The earthquake caught him in the kitchen, while he was serving himself a pinolillo. “I felt that the floor under me was moving like water, like the waves of the sea. First I grabbed the table and then I got under the table”, recalls the man who spilled the pinolillo on the floor due to the movement.

In his house, a wall in one of the rooms broke and the bathroom, which was built over a pit that many years ago functioned as a latrine, collapsed. He lived in old Managua, near the Bank of America building, and the first thing Rodríguez thought was that the building had fallen, but when he went out into the street, he saw that the building was still standing, but the houses on the street where he lived were totally destroyed.

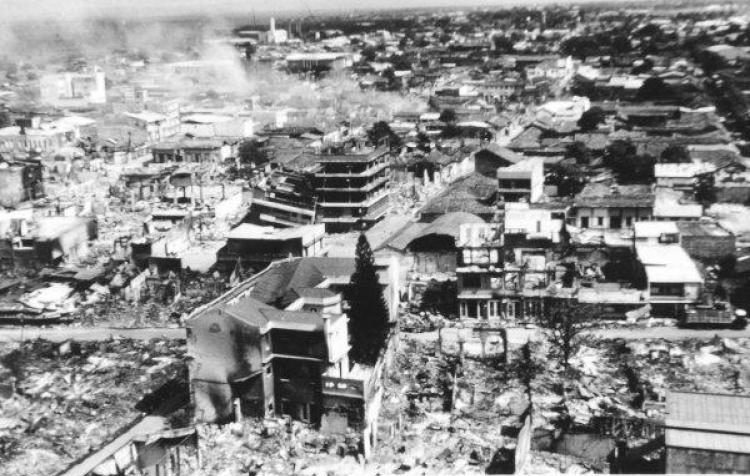

In another sector of the capital lived Mariana Rosales, who at that time was 23 years old, remembers that many old buildings collapsed. “Managua was bald,” she says, to describe how only a small part of the big buildings of old Managua were left standing.

Managua, despite the fact that it was very beautiful, did not have strong buildings and that was one of the main reasons why many homes collapsed. Most of the houses were built of taquezal, which was a kind of slab made of mud, mud, and grass.

The collapse of the old buildings raised a huge cloud of dust over the city. The electricity was cut off and small fires broke out in several areas that took several days to put out. That night, the moon and stars were obscured by smoke and dust.

Rosales and Gutiérrez agree when recounting how in the streets people could be heard shouting for help from the rubble. They were cries for help, pain, fear, crying. Then the rumors began that an entire neighborhood had disappeared, and those that were next to it too. Distributions, residential and apartments. All down and turned to rubble in just 30 seconds.

The Managuas were still trying to assimilate what happened when suddenly the earth moved again. A second tremor, which according to Gutiérrez “made the earth ring” at about two in the morning, ended up knocking over the buildings that were left weak by the first quake.

The dead. First they were counted one by one. After two by two. Then three, five, ten, until they became uncountable. Hospital structures also collapsed. Only the old El Retiro hospital was left standing, although with serious damage to the building. The wounded arrived in droves and quickly saturated the corridors and rooms of the hospital. Many wounded had to be located in the hospital courtyards.

The former rescuer, Clemente Balmaceda, told the newspaper La Prensa in 2017, that when he arrived at the Red Cross headquarters after the earthquake, he found that the two-story facility had collapsed and the five ambulances had been left under the rubble and several volunteers on duty had died.

Related news: Nicaragua commemorates 49 years since the 1972 earthquake with a “multi-threat” drill

There were not enough rescuers to help the thousands of people who were left under the buildings that early morning, so the few who were had to improvise. The firefighters could not put out the fire that was advancing on the rubble and the few houses that were left standing.

The then commander of the Managua fire department, René Selva, also told the newspaper La Prensa in 2017 that he had ordered the station chief on duty to take the tanks out onto the street because he did not like the reddish color of the sky that night or the heat it was doing, but when he was replaced by another shift manager, he ordered the 16 cisterns to be put away, which would be crushed. An hour later, there were no tanks to put out the fire that was over Managua.

Dark Dawn

At dawn on that December 23, the people of Managuas realized the magnitude of the event. It was not possible to circulate through the streets because they were destroyed and with debris on the tracks, food was scarce, there was no fuel, medicine, or water. Nor was there a lack of those who took advantage of the misfortune to rob shops or homes that were left abandoned.

In Bologna, the walls, ceilings, and entire walls that are built for solid residences, were crumbling. “The Juvenile Reformatory, a rectangular structure, had slid from west to east, and it looked like a huge brush that was used in the past to scrape ice,” Ruiz described in his chronicle.

On May 27th Street, there were rows and rows of collapsed houses that reached as far as the old four-story Social Security building that was spread out on the street.

The survivors had to hold vigil for their dead impromptu in the few houses that were left standing, and some had to watch over their relatives in the street. In the midst of it all, people became aware of another shortage: there were not enough coffins.

The corpses of the deceased were so many that they had to be burned on public roads or in common graves due to the stench that they emitted due to the advanced state of decomposition. In the north highway sector, towards the González cinema and several more blocks, the smell of dead meat was unbearable, while birds of prey flew over the place.

Among the victims was a son that Rosario Murillo had with the journalist Anuar Hassan, after a wall of the house of the parents of the current vice president fell on him. As for Daniel Ortega, he had been detained in La Modelo prison since 1967 for assaulting a bank.

In Managua the radio did not work either, much less the television. The managuas were cut off from the world, until suddenly, a familiar noise was heard in the sky. It was a white plane that was making its first reconnaissance flight.

“It was nothing more than a plane, but at that moment it was a sign of life, an illusion that we Managuas had communion with something, however insignificant it was, and that that something was separated from that desolate and terrible panorama,” Ruiz recounted in his chronicle.

Soon after, an Army helicopter flew from east to west on the same reconnaissance mission as the fires already covered entire blocks and moved west of the city driven by the wind. “The fire continues to advance and it is not known how far it will go,” was the prognosis of a firefighter who was taking care of the ruins of what was the barracks.

By then, the government authorities had not yet ruled on the tragedy. At that time, a government junta headed by three people governed, which was called the triumvirate, while Anastasio Somoza Debayle was the head of the National Guard.

Somoza Debayle took advantage of the chaos generated by the earthquake and declared a Martial Law, which served him to gain true power in the country. To clean up the city, Somoza ordered the debris to be thrown onto the boardwalk, where the Salvador Allende port is located today.

Under Martial Law, the Guard also shot several looters. “Martial law has been declared. It will be applied immediately. Stop the robbery”, announced the Guard with a megaphone on the morning of December 24 so that people would stop looting the shops. Some of them were shot, according to Somoza Debayle’s admission in February 1973.

Rebuilding Managua took a long time. In fact, with the fall of the Somoza dictatorship in 1979, there were still several places in the capital that had not been rebuilt and there were allegations that Somoza was diverting international aid for his benefit.

Among the tallest buildings that existed at that time were the Bank of America, where the National Assembly is located today, and the Central Bank, which had 12 floors and, with the earthquake, only three remained. The few that withstood the earthquake also include the National Theater, the National Palace, the Margot cinema, the González cinema and the Intercontinental hotel (now Crowne Plaza).

The old Cathedral of Managua also survived, which is still standing, cracked and closed because at any moment it could collapse. It has witnessed the most historic moments of recent times, such as the triumph of the Sandinista Revolution in 1979.

For 50 years, the clock of this great gray mass continues to mark the time when everything stopped for the Managuas: 12:35 on December 23, 1972.